The Eastern Front 1914-1917 (18 page)

Read The Eastern Front 1914-1917 Online

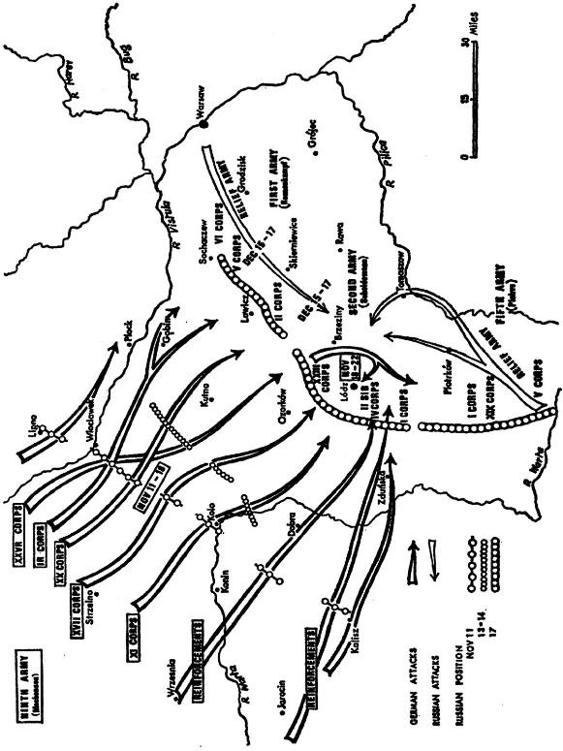

Authors: Norman Stone

Meanwhile, the Germans were supposed to be passively waiting on the borders to the west. It was thought that they would defend Silesia. Ludendorff had a different idea. He disliked having to co-operate with the Austrians, would be happier further north; he was also, by the hour, in receipt of Russian wireless-messages, now ably decoded. He appreciated the delays on the Russian side; knew that his own troops could be transported by rail. He transported most of IX Army in five days to Toruń, from where it could move south-east, into the flank of the Russian II Army, as it moved west to invade Germany. In the former positions north of Cracow, he agreed to leave the

Landwehrkorps

and the Guard Reserve Corps; to these, the Austrians added five divisions, taken as II Army from their troops in the Carpathians. These troops were sufficient to hold the Russian IV Army, while the Austrians held the attention of IX, III and VIII to the south.

Two manoeuvres were being planned—an advance by the Russian II and V Armies towards Germany, which Ludendorff proposed to counter by a great flank-attack on II Army. By attacking south-east from Toruń, he did find the weakest point in the Russian line. Most of the Russian divisions in central Poland had already been committed to the

Lódz, 1914.

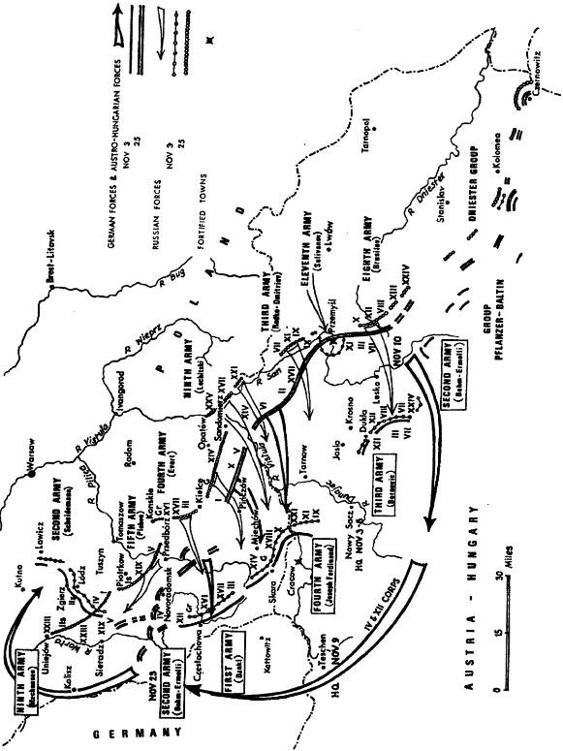

Galicia, 1914–15.

invasion of Germany, and could not easily react to this new threat to their flank. In any case,

Stavka

did not guess at what Ludendorff could have done, and told the front on 9th November that the Germans maintained ‘at least five-six corps at Czestochowa and Kalisz’—a message repeated three days later, and four days later by a personal letter of the Grand Duke to Ruzski.

Stavka

still, essentially, took this view after the German attack had begun—indeed, three days after its opening on 11th November.

7

Tactically, too, the Russians were unprepared for what was to come. II Army expected, legitimately, that its flank would be guarded by I Army. But I Army had a long front to control, opposite the southern frontiers of East Prussia, and it was too weak to cover all areas adequately. Ruzski also prodded its commander, Rennenkampf, towards East Prussia rather than towards the south. The corps on its left wing—5. Siberian—was isolated on the southern bank of the Vistula, its nearest neighbour (6. Siberian Corps) being some way to the north; the nearest bridge was fifty miles upstream, and although a makeshift bridge was built closer than this, it broke down under the weight of heavy guns. One of the divisions was still supplied from the fortress of Novogeorgievsk; another had no technical equipment, and the corps as a whole had only thirty-five small spades per company. The commander, Sidorin, responded fitfully to these circumstances—half-digging first one position, then another.

When, on 11th November, three German corps with five times Sidorin’s artillery attacked, his force inevitably collapsed—his artillery (all but fifteen guns) typically saving itself while two-thirds of the men were made prisoners. The rest of the corps went back along the Vistula and a gap of thirty miles opened between the river and the right of II Army. Ruzski did not see this. He still thought the Germans were far to the south-west, and, having little faith in the second-line troops under Sidorin, ascribed their defeat to at most two German divisions, making a feint. The only response, both on his and

Stavka’s

part, was to encourage II Army to hurry up with the invasion of Germany, V Army to help it. The Germans had only fifteen divisions to the Russians’ twenty-four, but strategically their situation was much superior. Of the five corps of II Army, four were already some way to the west; and the fifth was already attacked in front and flank by the German IX Army. On 14th and 1 5th November, the Russians suffered a further tactical reverse of some seriousness. The right-hand corps of II Army was almost overwhelmed; and a single German reserve corps (under Morgen) held off the attacks of such reinforcements as the Russian I Army had managed to send over the river to help 5. Siberian corps.

Only on 15th November did the Russian commanders appreciate quite what had happened. II and V Armies prudently decided not to go

on with the invasion; instead, they swung about, to go back east on their supply-centre, the large town of Lódz. They performed something of a miracle, marching almost without stopping for two days and more, and reached Lódz before the Germans, marching south-east, could do so. When the first German troops arrived, they found seven Russian corps on the perimeter of Lódz—a manoeuvre that, in the end, saved the battle for the Russians. For the moment, none of the Russian senior commanders appreciated the virtuosity of II Army’s performance.

Stavka

announced to Ruzski its ‘extreme irritation at some of your senior commanders’ dispositions’; of the retreat, Ruzski complained, ‘Everything has followed from this blunder. The details are not worth going into, they’re too depressing’. Both

Stavka

and Ruzski wanted a concentric attack—the troops brought over the Vistula by I Army, the troops in Lódz, and the corps of II Army that had been defeated in detail a few days before. These orders sometimes did not reach the army commanders, who in any case were hardly in any position to execute them. By 18th November they were content merely to hold Lódz against Germans, rapidly arriving. Ludendorff as often before and later imagined he had won a great strategic success, instead of a good tactical one. He thought the Russian armies were now retreating to the Vistula, and sent his men against Lódz in the hope of cutting the Russians off before they could accomplish their retreat. In practice, he was running into a trap. II and V Armies were not only defending Lódz, they were better able to do so than the Germans to attack it, for it was their supply-centre. They also out-numbered the Germans—on the western sector, thirty-six battalions and 240 guns to sixty-four and 210, on the northern sector thirty-six and 240 to seventy and 170, in a terrain greatly favouring the defender. By 22nd November, many German units had run out of munitions—one corps having only seventy rounds left per battery of six guns. German attacks slackened, failed.

Only in one area, east of the town, was there still a gap in the defence. A German reserve corps and a Guard division—thirty battalions and 140 guns—had reached it before the retreating Russians could; following Ludendorff’s instructions, they moved south-east to cut off a Russian retreat they supposed to be occurring. On the Russian side, not much, initially, could be done. In Lódz the defenders were held along the city perimeter. Further north, I Army command was still sorting out the troops hit first at Wroclawek, on 11th–13th November, and then at Kutno on 14th–15th November; a thin German cordon sufficed, for the moment, to contain most of I Army and even to drive it back. In the circumstances, there was nothing substantial in the path of the three German divisions. They went on to the south, then turned west towards Lódz. Here they

met Russian troops hurriedly sent to the city’s eastern side, and although they were only twenty miles from the German western wing, the three divisions were held, by 21st November. Their situation was dangerous—they could not break out to the west, south or east; and their passage to the north might be blocked by a reviving Russian I Army. By the 22nd Russian troops did indeed take Brzeziny, on the road to safety in the north. What followed was an illustration of the superior quality of German reserve divisions, for a force of lesser quality would simply have been taken prisoner—indeed, Danilov ordered trains brought up to take the expected 50,000 prisoners back to Russia.

But Scheffer, commanding the German reserve corps, kept his force together. Cavalry to the south and east co-operated with him, covering the retreat; Scheffer himself stayed awake for seventy-two hours to organise retreat along poor, icy roads as his battalions and batteries withdrew, in the night of 22nd-23rd November. The retreat succeeded. On the western side, the Lódz defenders were too exhausted to react with any speed. On the southern side, German cavalry put up a considerable performance, and the Russian commander there, far from pressing the retreating Germans, even demanded congratulations and promotion for his fine defensive performance. To the east, Russian cavalry seems to have supposed, from the numbers of prisoners accompanying Scheffer on the march, that the Germans were much stronger—the prisoners having been assumed to be German soldiers. On the northern side there was a remarkable piece of muddle. I Army had organised a force of one and a half infantry-divisions (second-line) and two cavalry divisions, collectively known as ‘Lowicz detachment’. It marched south-west towards Lódz. But it did so reluctantly. Rennenkampf had conceived his task as being essentially defensive, protection of Warsaw. Ruzski, even more bemused, changed from irrelevant bellicosities to craven defensiveness overnight, and

Stavka

was powerless to put across its occasional intimations of reality. The German force east of Lódz was put at three corps by a British military observer attached to the Lowicz detachment. Its commander, Slyusarenko, advanced five miles towards Lódz and then retired. Rennenkampf sent a different commander, Shuvalov; Ruzski sent another one, Vasiliev, who won. By 23rd November the force arrived in Scheffer’s rear. But one division went to the west, and became confused among the defenders of Lódz. The other dug in along a railway-embankment. At dawn on 24th November, the German Guard division brushed pasta weak force on Scheffer’s left, and re-took Brzeziny. More significantly, the two reserve divisions under Scheffer’s control managed to break through the defenders of the railway-embankment—although these two divisions were second-line ones and, at that,

troops that had been marching and fighting for a considerable time. The Russian divisional commander, Gennings, suffered nervous collapse, and only 1,600 of his men were collected by the Lowicz detachment. In this way, the three German divisions were able to retire to the north-west and to link up with the rest of IX Army. They brought back 16,000 prisoners. As a final touch to this epic of inappropriateness on the Russian side, the commander of 2. Corps, to the north, announced that Scheffer’s group was attacking him, and demanded help from Gennings.

9

The affairs of Ruzski’s command had now reached a pitch of confusion that seemed to demand retreat from the exposed positions of his armies around Lódz. II and V Armies had lost, between them, 100,000 men. Hospitals in Lódz, built for 5,000 men, were taking ten times as much. Rifles were running short—or rather, would have done had the troops not been reduced, in many cases, to a third of their complement. The shell-reserve was low—only 384 rounds per gun—and because communications were disordered, batteries at the front had considerably less than this. Even boots were running short, and Ruzski claimed that, where he needed half a million pairs, his reserve consisted of less than 40,000.

10

It was at least clear that the invasion of Germany could not occur. Ruzski had concluded from the events of Lódz that no advance towards Germany could be made so long as the flank was unsecured—in other words, the armies must be prepared for an offensive against East Prussia. Until this could happen, there was no sense in holding exposed positions in Central Poland—better to retire to the line of the Vistula. In the meantime, the Germans were once more threatening the Lódz positions. Ludendorff managed to persuade highly-placed Germans that Lódz had been a great strategic victory, not a complicated draw with tactical advantages on the German side. He bludgeoned Falkenhayn, Moltke’s successor as effective German commander-in-chief, into sending further troops—four corps under Linsingen, Fabeck, Beseler and Gerok. Falkenhayn had grumbled that transfer of troops to the east was dangerous; the war could only be won by attacking the British, ‘with whom the enemy coalition stands or falls’; ‘in the last analysis’ defeat on the Marne was to be explained by ‘weakening of the western armies for the sake of the

Ostheer

’. But German defeats in Flanders removed some of the force of these arguments, and reinforcements went east by early December. Ludendorff planned another offensive in central Poland. In the circumstances, Ruzski was still more adamant on retreat than before—although initial German attacks, launched frontally by the new corps, made little headway.