The Eastern Front 1914-1917 (20 page)

Read The Eastern Front 1914-1917 Online

Authors: Norman Stone

In the main offensives, it was the Austrians who were first off the mark, with forty-one divisions to thirty-one infantry and eleven cavalry divisions, on 23rd January. An Austro-Hungarian army was to seize the passes of the western Carpathians,

Südarmee

those of the centre, and further east, in the flatter area of the Bukovina, a further Austro-Hungarian group was to seize the Russian flank. The offensive maybe looked sensible on a map. On the ground, it was—in the words of Austrian official historians whose kindness to Conrad amounts to considerable distortion—‘a cruel folly’. Mountains had to be scaled in mid-winter; supply-lines were either an ice-rink or a marsh, depending on freeze or thaw; clouds hung low, and obscured the visibility of artillery-targets; shells either bounced office or were smothered in mud; whole bivouacs would be found frozen to death in the morning.

16

Rifles had to be held over a fire before they could be used; yet even the thick mountain-forests were of no great help for fuel, since there was no way of transporting logs out of these primaeval forests. The task was altogether a grotesquely inappropriate one, but Conrad’s staff, comfortably installed in their villas in Teschen, with their wives in attendance, waved protests aside, even when they came from the reliable Boroević, commanding III Army. For better or worse, they had tied their strategy to a fortress, and like Haig at Passchendaele could see no other way of proceeding.

The offensive opened on 23rd January, Boroević taking the Uzsok Pass. On 26th,

Südarmee

also attacked, and went forward at a rate of perhaps a hundred yards a day. By the end of the month, it had taken a line south of passes it had been expected to take on the first day; and the arrival of a fresh Russian corps from Ruzski’s front held the line. Further east, the Austro-Hungarian attack did better, in flatter country where only Cossack groups offered resistance, and the river Dniester was reached on this side by mid-February. With this, the Austro-Hungarian offensive collapsed. It was followed, early in February, by a Russian offensive, against the western side. The Russians were closer to supply-lines than the Austrians; the Austrians had been exhausted by their own offensive; their positions in the valleys were often broken through, such that Austrian defenders on the mountains surrendered. There were persistent rumours, too, that the Slav soldiers of Austria-Hungary were giving in too easily—rumours perhaps exaggerated, for their own purposes, by both sides. By 5th February the western wing had fallen back over the railway centre of Mezölaborcz, through which ran an essential supply-line to the exiguous salient originally won by the offensive of 23rd January. Four divisions, counting ten thousand men altogether, were

spread out over twenty miles. Then the Russians ran into much the same problems as had bedevilled the Austrian offensive.

Conrad was now desperate to relieve Przemyśl, and could only repeat his offensive, for Kusmanek, commanding the garrison, said he would be starved out by mid-March. Twenty divisions were assembled on Boroević’s front for a new attack, but many of them existed only on paper. In any case, Boroević complained, and had half of the front taken from him, and given to another army commander, Böhm-Ermolli, who could be trusted to be more sparing with recognition of reality. In the mountains, things went much as before. Böhm-Ermoll’s counter-offensive opened on 17th February, but no-one noticed. Ice and snow condemned the troops to passivity, only the guns firing ineffectually at Russian lines. Throughout the latter part of February, troops were driven into piecemeal attacks that won at best a few hundred yards of snow. The main group of Böhm-Ermolli’s force—50,000 men under another general for whom Conrad had a mysterious fondness, Tersztyánszky—sank in a week to 10,000 men—bewildered, frozen, often not understanding what their officers were saying. Kralowetz, chief of staff to one of the army corps, later wrote that the Russians’ counter-attacks succeeded because they encountered ‘men already cut to pieces and defenceless… Every day hundreds froze to death; the wounded who could not drag themselves off were bound to die; riding became impossible; and there was no combating the apathy and indifference that gripped the men’. Some 800,000 men are said to have disappeared from the army’s fighting strength during the Carpathian operation—three-quarters of them from sickness. This was eight times the number of men supposed to be saved in Przemyśl. The Austro-Hungarian peoples paid heavily for Conrad’s inability to confess error.

Nothing, now, could save Przemyśl. Conrad’s adjutant confessed: ‘There is nothing more the troops can do’.

17

Falkenhayn would not send reinforcements—merely remarking that he had always predicted failure. Ludendorff had nothing to spare. Success in the Bukovina was too limited, too remote, to affect the issue. By mid-March, the Przemyśl garrison elected to surrender—making an attempt at a sortie that one British observer described as ‘a burlesque’.

*

On 22nd March, Kusmanek

Winter battle in Masuria, early 1915.

surrendered, with a garrison of 120,000 men. The way was now open for a full-scale Russian offensive in the Carpathians; and the direction of events on the other front, Ruzski’s, now inclined

Stavka

to take up this plan.

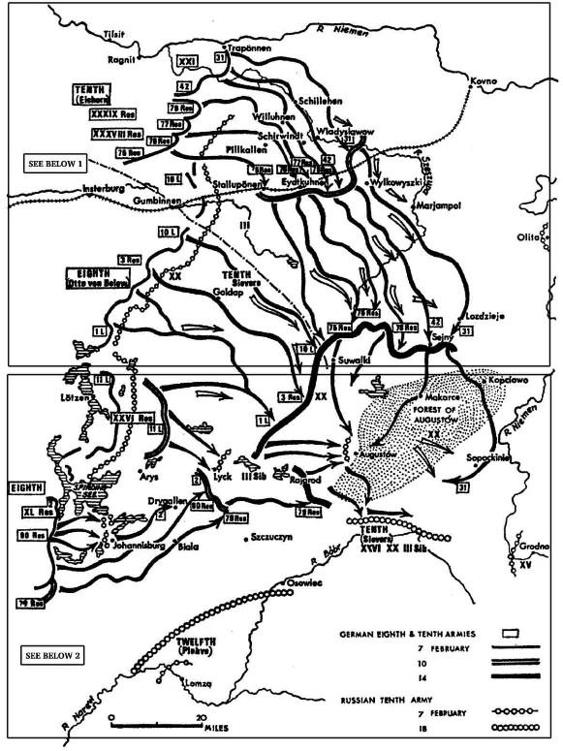

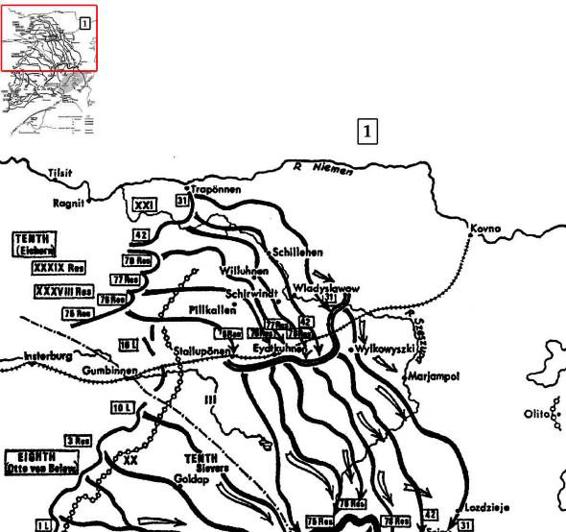

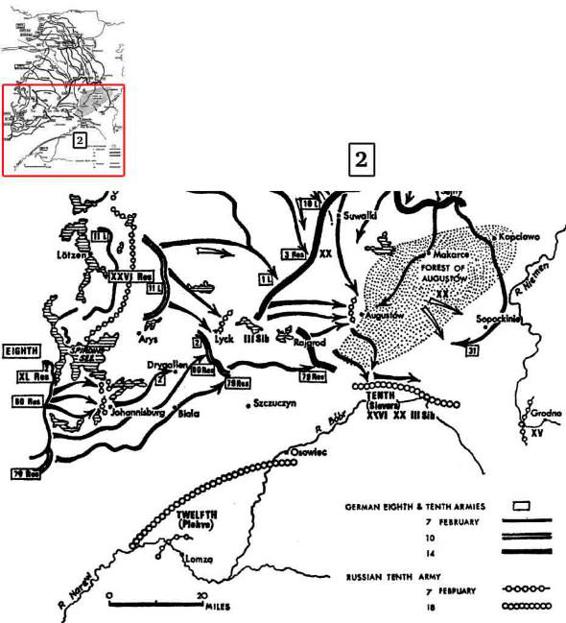

Late in January, Ludendorff moved his headquarters to Insterburg, in East Prussia. The four new corps, and those of VIII Army, together with troops drawn from the central front, were now to form two armies, in the eastern part of East Prussia—X (Eichhorn) and VIII (Below). There would be another ‘pincer-movement’—X Army from north of the Angerapp Lines, VIII Army from south of them, directed at the Russian X Army. The Germans had fifteen infantry and two cavalry divisions to eleven and two and some artillery superiority—seventy-seven light, twenty-two heavy batteries to 154 and forty-eight. In terms of numbers, the forces were roughly equal, at about 150,000 men. Ludendorff’s plan was bold, and in reality not very sensible. Weather counted against it, the attackers on occasion running into blizzards. No doubt a tactical success could be obtained. But as the two armies moved east, their southern flank would be lengthened, and on this there were substantial Russian forces, capable of acting offensively. But Ludendorff underrated the possibilities of this, and imagined he could force the Russians to evacuate Poland—Germans and Austrians pressing them from each flank.

The offensive got off to a good start, on 7th February. It led to a considerable tactical success—largely because the Russian X Army produced a repetition of earlier Russian patterns. In the first place, it was strategically isolated.

Stavka

and Ruzski were busy forming XII Army, to the south-west—six corps, to advance in mid-February against the southern frontier of East Prussia. Only two of its corps were in line, the rest not arriving till some time later—4. Siberian Corps and the Guard at Warsaw, 15. Corps at Gomel, 20. Corps still attached to X Army. Intelligence did as usual report German troop-movements in East Prussia. But the rumours were dismissed: on 6th February, Danilov was still saying that ‘they are probably distributing their forces in the central theatre’; while Ruzski s director of operations, Bonch-Bruyevitch, felt that ‘they will not dare to attempt anything in East Prussia, with XII Army on their flank’. Such alarms as occurred merely prompted acceleration of this new army’s concentration. Consequently, X Army was neglected, with no strategic reserve ready to assist it.

This would not, maybe, have mattered so much if X Army had been in reasonable condition. The proportions on its front were considerably less in the Germans’ favour than were proportions on the western front in the Allies’ favour; and yet the Allies generally failed to secure tactical victories of any scale, because German defences were sensibly-arranged.

A suitable method of defence could, in 1915, cancel out even three-fold superiority in guns, and more in numbers. But X Army did not have a sensible method. It had been disheartened by activities since August 1914—a lion-hearted crossing and re-crossing of the border, at much expense. Commanders had, seemingly, learned little—had even, in the case of Pflug,

19

been dismissed for attempting to apply such lessons as had been absorbed. The trench-system was primitive—at best a thin, interrupted, ditch, Over half of the divisions were second-line ones, containing only a tenth of their numbers from first-line troops; and since, in the Russian army, artillery commanders regarded such divisions as barely worth saving, there was always a tendency for guns to be saved at the expense of men. Moreover, the positions had been changed, on the right, shortly before. Following skirmishes further north, the right of the army had been pushed forward; and the expected co-operation of X Army with the offensive of XII had led to an over-extension of the front-line—on the right, to the edges of the Lasdehnen forest, where German troop-movements were effectively concealed. That two of the three divisions on the right had been told to garrison Kovno in case of emergency, did not lend X Army greater weight; while, to hold the newly-extended line, the commander—Sievers—had had to commit virtually all of his reserves to the front line. He warned Ruzski early in February: ‘Nothing can prevent X Army from being exposed to the same fate as I Army in September 1914.’

20

These fears were waved aside: XII Army would solve everything. Yepanchin, commanding the right, was similarly told not to bother commanders with his tales of woe.

The position worsened in the first two days of the offensive, because weather-conditions delayed the German attack, in its full weight; the German movements could be dismissed as ‘isolated groups’ such that the attackers gained much advantage from Russian commanders’ failure to respond. The whole of VIII Army, attacking on 7th February, was dismissed as ‘a small German detachment’. This army encountered, first, a relatively isolated second-line division, that regarded its main task as the protection of the fortress of Osowiec, to the south; the German attack was thought to be an attack on this, not on X Army’s flank. Most of this division disintegrated, though it lost only eight of its fifty guns. By 10th February, VIII Army had advanced some way into the left flank of the Russian X Army. Thereafter, a soldiers’ battle developed, as the Germans split their forces between attacks to south and east—both sets, in the event, held. The true tactical success came with the northern part of Ludendorff’s ‘pincer-movement’. On 9th February the full weight of this was felt, initially by two cavalry divisions on the extreme right. These broke up, ‘disappearing from the horizon’. The three second-line

divisions did not much better—suddenly struck, in frozen bivouacs. Yepanchin thought that an attack was being launched on Kovno, which he had been told to protect; and he led his men there, himself allegedly at their head. His divisions, unused to action, disintegrated—again, typically, losing only 17 of 150 guns, as artillery left the ‘cattle’ in the lurch. By 11th February, the Russian right had disintegrated, and German troops were stretched across the centre of X Army—by mid-February arriving in the rear of this centre, which contained three corps, one of which was engaged with VIII Army.