The Eastern Front 1914-1917 (50 page)

Read The Eastern Front 1914-1917 Online

Authors: Norman Stone

In these circumstances, the Kowel offensives turned into an expensive folly. The Germans were able to re-form their weak Austro-Hungarian partners, to the extent that the Austro-Hungarian IV Army became infiltrated, even at battalion level, with German troops. Its Austro-Hungarian command became a stage-prop, contemptuously shifted around by one German general after another. The method worked. Czech and Ruthene soldiery did not respond to Austro-Hungarian methods. But the arrival of competent German brigade-staffs, a battery

or two of German artillery, and some Prussian sergeant-majors was generally enough to lend the Austro-Hungarian troops a fighting quality they had not shown hitherto—‘corset-staves’, in the current phrase. In August, there was an extension of this method to all parts of the eastern front, and on the Kowel sector there were no more easy Russian victories. Just the same, Alexeyev went ahead, into mid-October. When huge losses were recorded, the commanders reacted as they had always done: there must be more heavy guns, and then everything would be all right. Evert, indeed, learnt so little from Kowel that for 1917 he demanded sixty-seven infantry divisions for a further offensive, with ‘814,364’ rounds of heavy shell, to be used on a front of eighteen kilometres.

11

As ever, when the old formulae failed, generals did not suppose that this was because the formulae were wrong, but because they had not been adequately applied. In the end, Russian soldiers were driven into attack by their own artillery: bombarding the front trenches in which they cowered.

The successes won by the Russian army in August were on parts of the front still subjected to the Brusilov method. XI, VII and IX Armies in eastern Galicia and the Bukovina ‘walked forward’, as before. XI and IX Armies in particular did this to great effect. Brody fell, and Halicz, in the south, as the multiple offensive on a broad front disrupted Austro-German reserves. It was the victories of IX Army that finally prompted Romania to intervene, since Lechitski’s drive almost brought the Russians into Hungary, and hence into occupation of lands coveted by the Romanians. Yet because so many Russian troops were now involved in the Kowel battles, there was almost nothing to back Lechitsky, whose victories were achieved with a mere eleven divisions of infantry (and five of cavalry). By the end of August, his drive had slackened, while the incurable tendency of Shcherbachev and Golovin, of VII Army, to apply French methods meant that Brusilov’s prescriptions were ignored, and the attacks against

Südarmee

turned into a minor version of Kowel.

These were the circumstances in which Romania intervened: Russian troops were pinned to the Kowel and Galician offensives; half of them were placed north of the Pripyat with almost nothing to do. Alexeyev himself had been told again and again that Romanian intervention would be decisive. Joffre had said that ‘no price is too high to pay for it’; Russian diplomats had been induced to promise Romania the areas of Austria-Hungary she coveted, and later on the Entente connived at Romania’s acquisition of Russian territory, Bessarabia. Alexeyev himself generally felt that Romanian intervention was not worth this much—on the contrary, it would be a liability.

12

At the turn of 1915–16, he had opposed schemes for bringing her in—the front would be lengthened; southern Russia would thus be exposed to a German attack through Romania; the

Russian army was not large enough to cover all of the area; the Romanian army was useless. In June, his attitude had changed to some extent, but he was never willing to make sacrifices for Romania, and now preferred to concentrate his troops on Kowel and Lwów. In any case, the railway-links between Russian and Romania were too weak to allow any rapid diversion of Russian troops. There were only two single-track lines connecting the two countries, even then with the usual problem of differing gauges. Late in November, Joffre managed to extract from Alexeyev a promise that Russian troops would assist in the defence of Bucharest; but since the Romanians could not offer even the sixteen trains per day needed for these troops, the proposal fell through. Alexeyev would give Romania only a small force—50,000 men (two infantry divisions and a single cavalry division) under Zayonchkovski. Otherwise, the Romanians must help themselves. The nearest Russian force was Lechitski’s IX Army, but it had only eleven divisions, was already engaged on the Dniester front, and in any case could not receive troops with any speed since communications were very poor and winter-conditions had already set in. Grudgingly,

Stavka

sent an extra corps to Lechitski, and concentrated its main efforts as before against Kowel.

Romania was virtually indefensible. The richest part of the country, Wallachia, jutted out in a long tongue between Hungary and Bulgaria: neither the Carpathians—traversed by many passes—nor the Danube offered real obstacles to an invasion, yet the Romanians could not simply abandon Wallachia, since this would mean loss of their capital. Their army could be easily split up between different functions, each of them difficult to discharge, and the Romanian high command complicated this problem still more by failing to give constant priorities to the various strategic tasks. Half of the army was switched, bewilderingly, between one front and the other. Romania’s intervention could only matter if the initial offensive against Hungary won an immediate success.

This did not turn out to be the case. To start with, nearly 400,000 Romanians crossed the Hungarian borders, and met opposition in the shape of the Austro-Hungarian I Army: 34,000 man, with a corps of miners volunteering to defend their pits to the west. Frontier villages were occupied, and the old Saxon town of Kronstadt, which lay in the south-eastern tip of Transylvania. But supply-problems turned out to be crippling. There was not much railway-communication between Hungary and Romania, and that little was badly-managed. The paths through the mountains could often accommodate only troops moving in single file, not carts or guns. Commanders behaved ineptly, and seemed to think that the prospect of meeting German troops dispensed them from further activity. Some of them even thought that, once they reached Central

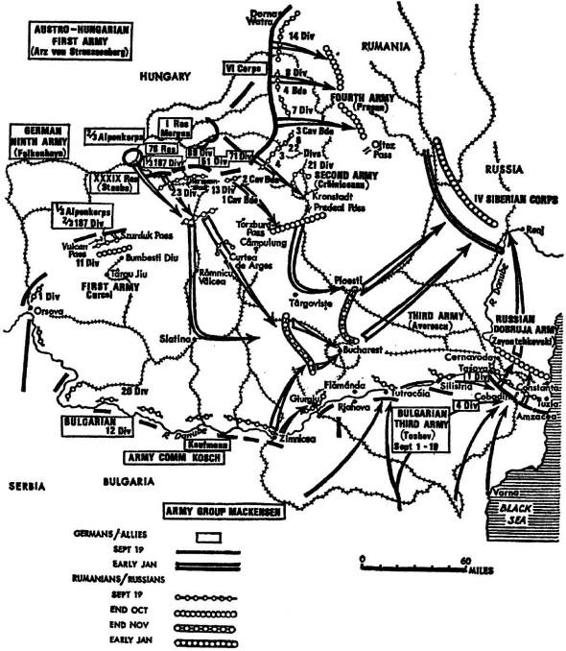

The Romanian campaign, end of 1916.

Transylvania, they would be so far from their supply-routes that catastrophe would intervene. In consequence, the Romanians did not even choose to occupy Hermannstadt, defended only by gendarmerie. They occupied the south-eastern tip of Transylvania, and waited to see what would happen.

The Central Powers’ plan was obvious enough. There would be an attack on the Romanians in Transylvania, combined with an attack along the Black Sea coast, into the Dobrogea—fertile lands, inhabited mainly by Bulgarians and stolen from Bulgaria in 1913, which the Bulgarians were keen to recover. The Romanians did not expect this attack. First, they thought that western Powers’ forces in Salonica would pin most of the Bulgarian army. This was not the case. The western Powers had enough on their hands to contain mosquitoes, let alone Bulgarians; in any case, their Greek allies were of such doubtful allegiance that an entire Greek army corps refused to fight at all, surrendered in toto and was interned in Silesia for the rest of the war. The attack from Salonica was a complete failure, and did not prevent Germans, Turks and Bulgarians from concentrating a substantial force against southern Romania. The Romanians had also expected Bulgaria to be deterred by the presence of a Russian force, Zayonchkovski’s, in the Dobrogea. In theory, the Bulgarians were Russophil; men even thought they might make peace once Romania entered the war on Russia’s side. This again was not the case. The Bulgarians hesitated about intervening; they even protested when German and Austro-Hungarian units stationed in Bulgaria took action against Romania (bombing Bucharest, for instance). But they decided in the end to declare war on Romania, a day or so after their allies. In this way, a joint offensive of all four Central Powers became possible. Moreover, the railways that fed reserves to Transylvania were superior to anything on the Romanian side. By the third week of September, the Central Powers’ forces had been stepped up to 200,000 men, half of them German. The Kowel offensive did almost nothing to prevent this.

The campaign opened with an unexpectedly successful feint attack by the Bulgarians and their allies in the Dobrogea. Mackensen, who commanded these forces, decided on a diversionary move against the Romanian fortress, Tutracǎia, on the Danube. A besieging force, actually smaller than the garrison, moved up. The fortress’s commander announced to an assemblage of foreign journalists that ‘Tutracǎia will be our Verdun’. It fell the next day, eighty per cent of the garrison surrendering, and the rest fleeing, their commander in the lead. By 8th September, Silistria also had fallen, this time without even spoken resistance. The Bulgarians and their allies crossed the border and invaded the Dobrogea. Here they were due to encounter Russian forces. But the collaboration of Russians and

Romanians almost constituted an object-lesson in how not to run a multinational force. Zayonchkovski, though doing his best to maintain polite forms, complained again and again to Alexeyev that his task was impossible: to make the Romanian army fight a modern war was asking a donkey to perform a minuet.

14

Ordinary Russian soldiers regarded their allies with the utmost contempt, not least when these allies surrendered to Russian units, mistaking them for Bulgarian ones. Russians sacked the countryside in a dress-rehearsal for the agrarian atrocities of 1917: estates laid to waste, wine-cellars ruthlessly plundered, beasts’ throats cut, drunken soldiery drowned or boiled to death in vats of burning spirit. Russian officers quoted an old tag on Romania—

‘des hommes sans honneur, des femmes sans pudeur, des fleurs sans odeur, des titres sans valeur’

. The Romanians, at their allies’ mercy, could only exaggerate the Central Powers’ strength in the hope that more Russian troops would somehow be sent to save them. But Alexeyev was adamant: he felt that Wallachia and the Dobrogea should be given up, and the Romanian army withdrawn into the Moldavian mountains until it had absorbed the facts of modern war. A division was sent from Kuropatkin’s front in mid-September, and Lechitski was told to make better progress south of the Dniester. Otherwise, Russian help consisted mainly of renewed, futile attempts against the Kowel marches.

Threats to the Dobrogea compelled the Romanian high command to think again. On 15th September a crown council in Bucharest determined that wanderings in Transylvania should be suspended, to permit transfer of half of the army against Bulgaria. A ‘Southern Army Group’ of fifteen infantry divisions would be assembled under Averescu to cross the Danube into Bulgaria. Meanwhile, Zayonchkovski’s Russo-Romanian force (six and a half Romanian and three Russian divisions) would contribute an offensive against the Bulgarians who had arrived in the Dobrogea. A real enough superiority was gradually built up: 195 battalions, 55 squadrons and 169 batteries to 110, 28 and 72 on the Central Powers’ side. An attack was to be made between Zimnicea and Flǎmǎndǎ. It was a burlesque. Bridges were inadequate and broke down under the weight of guns and horses. Austro-Hungarian gunboats did much damage to the infantry as it tried to cross. Boats leaked. Such initial success as the crossings had was owing almost entirely to the deduction made by Kosch, German commander, from the Romanians’ behaviour that they were only there to defend Bucharest. By 3rd October, after a few hours’ action, the Flǎmǎndǎ enterprise had to be abandoned. In the Dobrogea, things took a similar course, with the complication that Romanians misunderstood Russian orders, and in any case were not keen on obeying them.

This strategic manoeuvre had been achieved at the cost of Romanian

positions in Transylvania. Here, only ten divisions had been left—less than the Central Powers, with twelve. Moreover, the Romanians’ advance had been of the worst possible kind. It had brought them beyond their own lines of supply, but it had not brought them forward to any point where they could disrupt the arrival by rail of the Central Powers troops. By mid-September, a German IX Army had been established (as a grim joke under Falkenhayn’s command) to co-operate with the Austro-Hungarian I Army. The various Romanian groups stood in isolated blocks just north of the Carpathians : usually in utter ignorance as to each other’s whereabouts, and with no possibility of establishing rapid contact in battle. Falkenhayn drove against one of these isolated corps, at Hermannstadt, and pushed it back through the Turnu Roşu pass. The Romanian corps to its right, near Kronstadt, did not learn anything of this, and was itself driven back with much loss over the mountains. By 6th October, Transylvania was once more virtually completely in the hands of the Central Powers. Now Falkenhayn could cross the mountains into Wallachia, and join up with Mackensen’s forces on the Danube. To avoid this, the Romanians decided to take back from the Danube the troops they had sent in the second half of September—such that nearly half of the Romanian army spent the first six weeks of war travelling between one front and the other. In the short term, this succeeded. The passes into Wallachia were blocked, and throughout October Falkenhayn’s groups had a difficult time, pushing through the snow from one defence-position to another on their way through the mountains. From time to time, Conrad von Hötzendorf suggested more ambitious plans: a great offensive towards Bucharest, from the passes just to north-west of it. This plan, though subsequently praised by Liddell Hart, made too little sense on the ground for it to be adopted. Throughout October, the Central Powers’ action here was more important for the troops that it pinned than for the ground it gained.