The Egyptian Royals Collection (162 page)

Read The Egyptian Royals Collection Online

Authors: Michelle Moran

Tags: #Bundle, #Fiction, #Historical, #Literary, #Retail

C

LEOPATRA’S

AUGHTER

1. What, if any, elements of the Ancient Roman world seem similar to life today?

2. In the beginning of the novel, Octavian comes across as a ruthless man willing to do whatever it takes to stay in power. Does anything change as the story progresses? How do you feel about him in the end? Did your feelings change at all? Why do you think he treats Selene the way he does as the novel closes?

3. Selene has a complex relationship with Julia. Do her feelings about Julia change during the course of the novel? If so, why?

4. Octavian/Augustus governed Rome for decades; sometimes with guile, often with ruthless force. In the novel, we see his use of assassinations (of rivals, real and imagined) as well as collective punishment following the attempt on his life. Can this leadership style be justified by his focus on order and stability? In their quest for these, what boundaries should leaders never cross?

5. Selene has two romantic interests in the novel. How does her attitude and character change as she matures and passes from one romance to the other?

6. Octavia shows tremendous compassion for the adopted children placed in her care. How would you have responded to a betrayal like that of Antony?

7. The slave trials described in the novel were real examples of Roman collective punishment. How does the administration of justice in classical times differ from the modern ones we know today?

8. Was the Roman system of law, administration, learning, and empire a net gain or a net loss for those that it conquered?

9. Egypt has always fascinated outsiders, including, in this novel, Julia. Why?

10. Omens, superstitions, and protection by family spirits play a significant part in the novel and in Roman life. What is the source of these widespread human traditions, and how do such emotions and habits express themselves today?

11. How does the Roman attitude toward marriage, sex, and promiscuity compare to our own?

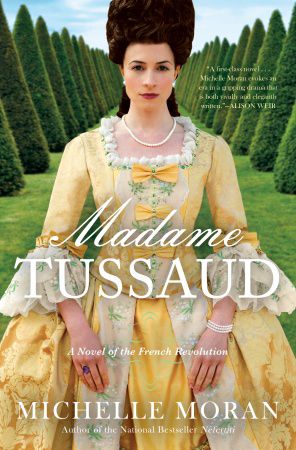

Go to the next page to read the first three chapters of Michelle Moran’s latest novel:

Madame Tussaud

$25.00 hardcover (Canada: $28.95)

ISBN 978-0-307-58865-4

ECEMBER

12, 1788

A

LTHOUGH IT IS MID-

D

ECEMBER AND EVERYONE WITH SENSE

is huddled near a fire, more than two dozen women are pressed together in Rose Bertin’s shop, Le Grand Mogol. They are heating themselves by the handsome bronze lamps, but I do not go inside. These are women of powdered

poufs

and ermine cloaks, whereas I am a woman of ribbons and wool. So I wait on the street while they shop in the warmth of the queen’s favorite store. I watch from outside as a girl picks out a showy pink hat. It’s too pale for her skin, but her mother nods and Rose Bertin claps her hands eagerly. She will not be so eager when she notices me. I have come here every month for a year with the same request. But this time I am certain Rose will agree, for I am prepared to offer her something that only princes and murderers possess. I don’t know why I didn’t think of it before.

I stamp my feet on the slick cobblestones of the Rue Saint-Honoré. My breath appears as a white fog in the morning air. This is the harshest winter in memory, and it has come on the heels of a poor summer harvest. Thousands will die in Paris, some of the cold, others of starvation. The king and queen have gifted the city as much firewood as they can spare from Versailles. In thanks, the people have built an obelisk made entirely of snow; it is the only monument they can afford. I look down the street, expecting to see the fish sellers at their carts. But even the merchants have fled the cold, leaving nothing but the stink of the sea behind them.

When the last customer exits Le Grand Mogol, I hurry inside. I shake the rain from my cloak and inhale the warm scent of cinnamon from the fire. As always, I am in awe of what Rose Bertin has accomplished in such a small space. Wide, gilded mirrors give the impression that the shop is larger than it really is, and the candles flickering from the chandeliers cast a burnished glow across the oil paintings and embroidered settees. It’s like entering a comtesse’s salon, and this is the effect we have tried for in my uncle’s museum. Intimate rooms where the nobility will not feel out of place. Although I could never afford the bonnets on these shelves—let alone the silk dresses of robin’s-egg blue or apple green—I come here to see the new styles so that I can copy them later. After all, that is our exhibition’s greatest attraction. Women who are too poor to travel to Versailles can see the royal family in wax, each of them wearing the latest fashions.

“Madame?” I venture, closing the door behind me.

Rose Bertin turns, and her high-pitched welcome tells me that she expects another woman in ermine. When I emerge from the shadows in wool, her voice drops. “Mademoiselle Grosholtz,” she says, disappointed. “I gave you my answer last month.” She crosses her arms over her chest. Everything about Rose Bertin is large. Her hips, her hair, the satin bows that cascade down the sides of her dress.

“Then perhaps you’ve changed your mind,” I say quickly. “I know you have the ear of the queen. They say that there’s no one else she trusts more.”

“And you’re not the only one begging favors of me,” she snaps.

“But we’re good patrons.”

“Your uncle bought

two

dresses from me.”

“We would buy more if business was better.” This isn’t a lie. In eighteen days I will be twenty-eight, but there is nothing of value I own in this world except the wax figures that I’ve created for my uncle’s exhibition. I am an inexpensive niece to maintain. I don’t ask for any of the embellishments in

Le Journal des Dames

, or for pricey chemise gowns trimmed in pearls. But if I had the livres, I would spend them in dressing the figures of our museum. There is no need for me to wear gemstones and lace, but our patrons come to the Salon de Cire to see the finery of kings. If I could, I would gather up every silk fan and furbelow in Rose Bertin’s shop, and our Salon would rival her own. But we don’t have that kind of money. We are showmen, only a little better-off than the circus performers who exhibit next door. “Think of it,” I say eagerly. “I could arrange a special tableau for her visit. An image of the queen sitting in her dressing room. With

you

by her side.

The Queen and Her Minister of Fashion,”

I tell her.

Rose’s lips twitch upward. Although Minister of Fashion is an insult the papers use to criticize her influence over Marie Antoinette, it’s not far from the truth, and she knows this. She hesitates. It is one thing to have your name in the papers, but to be immortalized in wax … That is something reserved only for royals and criminals, and she is neither. “So what would you have me say?” she asks slowly.

My heart beats quickly. Even if the queen dislikes what I’ve done—and she won’t, I

know

she won’t, not when I’ve taken such pains to get the blue of her eyes just right—the fact that she has personally come to see her wax model will change everything. Our exhibition will be included in the finest guidebooks to Paris. We’ll earn a place in every Catalog of Amusements printed in France. But most important, we’ll be associated with Marie Antoinette. Even after all of the scandals that have attached themselves to her name, there is only good business to be had by entertaining Their Majesties. “Just tell her that you’ve been to the Salon de Cire. You have, haven’t you?”

“Of course.” Rose Bertin is not a woman to miss anything. Even a wax show on the Boulevard du Temple. “It was attractive.” She adds belatedly, “In its way.”

“So tell that to the queen. Tell her I’ve modeled the busts of Voltaire, Rousseau, Benjamin Franklin. Tell her there will be several of her. And you.”

Rose is silent. Then finally, she says, “I’ll see what I can do.”

ECEMBER

21, 1788

What is the Third Estate? Everything

.—A

BBÉ

S

IEYÈS, PAMPHLETEER

W

HEN THE LETTER COMES

, I

AM SITTING UPSTAIRS IN MY

uncle’s salon. Thirty wooden steps divide the world of the wax museum on the first floor of our home from the richly paneled rooms where we live upstairs. I have seen enough houses of showmen and performers to know that we are fortunate. We live like merchants, with sturdy mahogany furniture and good china for guests. But if not for Curtius’s association with the Prince de Condé when both men were young, none of this would be.