The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (54 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

Within a few weeks of the outbreak of war in August 1914 it was clear that this grand strategy was quite unreal. It was true that Germany's surface navy was soon driven from the high seas. In Southwest Africa and the South Pacific (though not in German East Africa where Von Lettow Vorbeck held out to the bitter end), German colonies were quickly seized. But British sea-power was not the great offensive weapon on which navy traditionalists had counted. The attempt to break through the Dardanelles in 1915 was an embarrassing failure. The British Grand Fleet spent the war in the Orkneys waiting for the Germans to venture into the North Sea. When they did so in 1916, there was no Trafalgar but only the inconclusive battle of Jutland. The role of the Royal Navy was vital but

defensive

, though it was ill-equipped to counter the submarine menace especially after February 1917 when the Germans turned to unrestricted submarine warfare. Tied down in the North Sea, it watched the rise of American sea-power in the North Atlantic, and its Japanese counterpart in the Western Pacific. Blockade was its primary means of attack: the slow remorseless pressure on the morale and physique of the German army and people.

2

But, even in 1918, it was uncertain whether it could work fast enough to stop Germany winning the war.

Instead, for the British, like their continental allies, the ‘real’ war was on land. Although the Germans were denied a

Blitzkrieg

victory in 1914, by the end of the year they controlled most of Belgium, including part of its coastline, and a large area of Northern France to within fifty miles of Paris. Far from intervening to restore the balance of power, the British now found themselves in a dangerous position. If France were defeated outright, or gave up an unwinnable struggle to evict the Germans, Britain would have suffered a catastrophic setback. German control of Belgium and its ports would destroy the benefits of British insularity. French defeat would end the cooperation that allowed naval concentration against Germany. It might mean German control over France's fleet. At best, the security of Britain – the imperial centre – would have been compromised in ways that weakened British influence around the world. At worst, the Germans would have taken a long step towards uniting the European continent against Britain's global pretensions. In either case, the implications for the stability and cohesion of the British world-system were stark.

It followed that, from the end of 1914 until the armistice of November 1918, the British war effort was dominated by the increasingly desperate struggle to reverse the early verdict of the fighting and escape the geopolitical nightmare threatened by failure to liberate Belgium and Northern France. Lord Kitchener, who had been brought into the Liberal government to take charge of the army, quickly realised that a vast new volunteer force must be raised for the continental war. He intended to hold it back for a decisive blow, perhaps in 1917, when the continental powers had fought themselves to a standstill. This would ensure a loud British voice in the subsequent peace, an echo of the Vienna treaty in 1815. He was too optimistic. The scale of German success against the Entente powers forced a premature offensive in 1915. In 1916, the disasters on the Eastern Front,

3

and the attrition of France's manpower at Verdun, forced the British into a reluctant offensive on the Somme that was abandoned after 400,000 casualties. After two years of war on the Western Front, and a quarter of a million British dead, there had been no progress on the most vital of British war aims.

Indeed, by the end of 1916, the military problem seemed all but insoluble – except to the generals. To win on the Western Front, the British and the French had to drive the Germans from positions they had seized and fortified in the opening phase of the war. They had to achieve this against an enemy enjoying all the advantages of interior lines. As an attack developed, the Germans could shuttle their reinforcements across the battle zone by rail: the attackers had to walk through mud and barbed wire. Moving into the open exposed the attacking force not just to rifle and machine gun fire, but to the deadly barrage of heavy artillery, which inflicted three-quarters of all casualties. With little chance of a decisive breakthrough, the only means of breaking the enemy's will was through ‘attrition’: forcing German troops to fight, at whatever cost, in the hope of eventually wearing down their reserves of manpower and morale. With so desperate a strategy, and so few signs of success, it was hardly surprising that by November 1916 a mood of pessimism engulfed most of those responsible for the war effort of the British Empire.

4

These were the circumstances in which the coalition government that Asquith had formed in May 1915 was overthrown by a political coup in December 1916. The new coalition led by Lloyd George, with some Liberal but more Tory support, signalled the determination to win and to mobilise every resource for victory. But Lloyd George, who grasped better than anyone the political and technical difficulties of a total war, and Lord Milner, who became his chief lieutenant, were both keenly aware of how the drain of blood on the Western Front would affect the deeper sources of British power. Even with conscription to filter the call-up of skilled men, the huge losses of attrition warfare would weaken the British economy, limit its war production and cut down the exports that helped pay the inflated bill of vital imports. Economic exhaustion would accelerate war-weariness, starve Britain's allies of the material they needed and might break both the will and the means of victory. Despite these misgivings, no alternative plan was possible in 1917.

5

Instead, the pressure grew for even greater sacrifice on the Western Front. The gradual collapse of the Russian army, the threatened collapse of the French – whose losses had been far higher than the British – made a new offensive against the German line a grand strategic necessity. This was Passchendaele: a battle in the mud from July to November 1917 that cost the BEF over 220,000 dead. Yet, by the end of 1917, as the Bolshevik revolution dragged Russia out of war, the prospects for victory in the West looked darker than ever. Triumph in the East would give the German High Command just the reinforcements it needed to break the Allied line, seize the Belgian coast and capture Paris. If it moved fast enough it could pre-empt the arrival of American troops and smother the impact of the United States’ decision

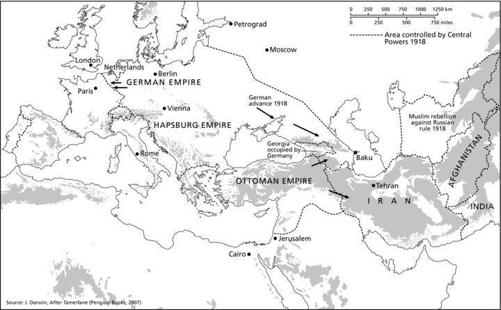

Map 9 The First World War in 1918

to enter the war (a result of Berlin's unrestricted submarine warfare) in April 1917. It could win the battle for Europe.

The spring and summer of 1918 thus turned out to be the climax of the war, the moment at which for the British and their allies defeat came closest. This was the ‘new war’ against which Milner warned Lloyd George in March 1918. With the signature of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk (6 March), the Germans had won the war against Russia ‘which used to cover our whole Asian flank’. With the Germans poised to swing round the Black Sea and enter the Caucasus, and the Turks now freed from Russian pressure, ‘we have a new campaign which really extends from the Mediterranean shore of Palestine to the frontier of India…[W]hether or not Japan takes on North Asia – I doubt her doing it – we alone have got to keep Southern Asia.’

6

The next day, the expected German blow fell in the West, but with unexpected force. Within days it had shattered the British Fifth Army in its path. ‘We are very near a crash’, wrote the government's chief military adviser, Sir Henry Wilson, on 24 March.

7

A week's fighting cost the BEF 114,000 men. ‘You must fight with your backs to the wall’, Haig, their commander, told his troops (the irreverent reply was: ‘where's the wall?’). As the Germans pressed forward, the British faced the dilemma of abandoning the Channel ports or losing touch with the French armies to the south. ‘No readjustment of our forces can save the situation’, said Milner (now Secretary of State for War) until the British and French divisions began to hold their ground against the Germans.

8

‘We are a fast dwindling army’, wrote Wilson on 12 April. ‘This is desperately serious.’

9

By early June, with the Germans at the Marne, and shells falling in central Paris, British leaders began to ponder how they would fight on if France and Italy (where a new German-Austrian offensive was expected) gave up the struggle. ‘The United States too late, too late, too late: what if it should turn out to be so?’, groaned the American ambassador to his diary.

10

Milner was in no doubt that the supreme crisis of the war had arrived. ‘We must be prepared for France and Italy being beaten to their knees’, he told Lloyd George. ‘In that case, it is clear that the German-Austro-Turko-Bulgar bloc will be master of all Europe and Northern and Central Asia up to the point where Japan steps in to bar the way.’

11

Milner predicted a global war in which Britain and her allies would be forced to defend the maritime periphery against a ‘heartland’ dominated by German power. ‘It is clear’, he argued,

[t]hat unless the only remaining free peoples of the world, America, this country and the Dominions, are knit together in the closest conceivable alliance and prepared for the maximum sacrifice, the Central bloc under the hegemony of Germany will control not only Europe and most of Asia but the whole world…If all these things happen, the whole aspect of the war changes. These islands become an

exposed outpost

of the Allied positions encircling the world – a very disadvantageous position for the brain-centre of such a combination.

The fight, he concluded, ‘will now be for Southern Asia and above all for Africa (the Palestine bridgehead is of immense importance)’.

12

Here was a terrifying prospectus of Britain's imperial future from the most ardent of imperialists. The old balance of power had vanished like a dream. Britain's eastern empire now lay open to an attack far more dangerous than anything threatened by Russia in the days of the ‘great game’. Japan's domination of East Asia, foreshadowed in its ‘21 demands’ to China in 1915, would be the price of its support. American financial and military help would be more indispensable than ever, strengthening when peace came the American demand for the ‘freedom of the seas’ and the international settlement of colonial claims: key elements in Woodrow Wilson's ‘Fourteen Points’ published in January 1918. The ‘new world’ taking shape by the middle of 1918 bore a frightening resemblance to the warnings of Halford Mackinder, the geographer and imperialist, some fourteen years before: a vast ‘heartland’ (ruled by Germany) controlling the ‘world island’ (continental Europe, Asia and Africa) leaving only an outer fringe where sea-power could contest its claims. With Britain and India under siege, and London's commercial empire in ruins, the rump of the British world-system would have little choice but to look to the United States as its saviour.

We know in hindsight that Milner was too pessimistic. Within a month, the tide in the West had begun to turn. But his grim prognosis left a fateful imperial legacy. Failure on the Western Front, perhaps a ‘Dunkirk’ in which the British army abandoned the continent, made the Middle East the new fulcrum of imperial defence. It was there that the road must be barred to the Central Powers whose victory in the region would cut the British system in two and roll it up in detail. In the first part of the war this had hardly seemed likely. British ambitions had been correspondingly modest. But in 1918 they aspired to dominate the whole vast tract between Greece and Afghanistan, obliterating the Ottoman Empire in the process. Their moment in the Middle East began in earnest.

This great forward movement was a startling reversal of pre-war policy. Before 1914, the British had been favourable to the expulsion of the Ottomans from Europe, but opposed to the break-up of their empire in Asia. Long-standing fears of Russian or German attempts to disrupt the route to India and penetrate the Persian Gulf – the maritime frontier of India – made Turkish control over the Straits and the Arab lands the least worst solution. But, in October 1914, the Turkish military triumvirate that ruled the empire threw in its lot with the Central Powers, perhaps in fear that an Entente victory would bring Russian annexation of Constantinople and the Straits, the oldest and dearest of Tsarist war aims. The British now had to defend their ‘veiled protectorate’ in Egypt and their ‘virtual’ protectorate in the Persian Gulf, whose Arab statelets were superintended by the government of India, against Ottoman attack. They had to protect the oil concession at the head of the Gulf (in Persian territory but close to the Ottoman border) half-owned by the British government and intended to supply the Royal Navy. Above all, they had to blast open the Straits so that supplies could reach their vast but almost landlocked Russian ally and turn its huge manpower to account. At the same time, they had to think how to minimise the effects of Turkish defeat upon the ‘post-war’ security of their imperial system, when both France and Russia (it had to be assumed) would be victor powers and (soon) new rivals. Their instincts were cautious. Their first preference was to keep the Ottoman Empire in being but force it to decentralise into zones of interest shared out between the victors. In May 1915, with the attack on the Dardanelles, the Russians were promised Constantinople and the Straits, while the British were to take in compensation the large ‘neutral’ zone between the Russian and British spheres of influence in Persia. In May 1916, in a further effort to pre-empt any post-war dispute, the Sykes–Picot (or ‘Tripartite’) agreement proposed a comprehensive partition of the Ottoman lands. Russia was to receive (as well as the Straits) a large sphere of interest in Armenia, or eastern Anatolia. Much of central Anatolia, and the coastal lands of the Levant went to France. The British share was to be the provinces of Baghdad and Basra, in the southern part of modern Iraq. The remainder of Turkey's Arab territories (most of modern Syria, northern and western Iraq, Jordan and southern Israel) was divided into two zones, in each of which the British and French would enjoy an exclusive influence over autonomous states ‘under the suzerainty of an Arab chief’.

13

Palestine was to be internationalised.