The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (169 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

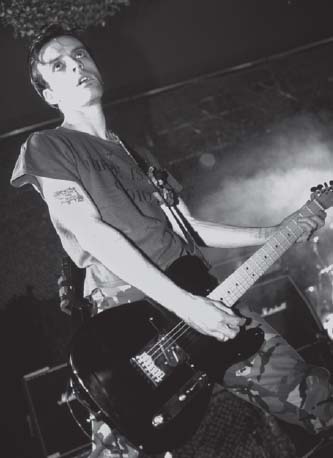

(Blackwood, South Wales, 22 December 1967)

The Manic Street Preachers

Richey Edwards: Out there?

Although no concrete evidence had manifested itself in almost fourteen years since his disappearance, former Manic Street Preachers guitarist Richey James Edwards was officially declared dead on 23 November 2008, his family having eschewed the option six years previously. In terms of striking a chord, Edwards’s disappearance ahead of an imminent US tour seemed to echo the final days of Joy Division singer Ian Curtis (May 1980);

in this case, however, there has never been closure.

In his youth, Edwards shunned the conventions of education - though he emerged from Cardiff University with a degree - burying himself in literature, which stirred within him a desire to write. The young Edwards read widely (including the complete works of Shakespeare by his sixteenth birthday), his predilection for hiding himself away for days while his contemporaries played football precursory to the dysfunctional public image fans later came to worship. With a history of mental problems, Edwards would in his adult and professional life undergo treatment for a variety of physical disorders: most disturbingly, he showed signs of the self-harm that was to cause sensation in 1991. With The Manics sometimes ridiculed for the sloganeering that accompanied much of their early output, Edwards took it upon himself to suggest that he, at least, was genuine, carving the words ‘4 REAL’ into his arm in front of stunned journalist Steve Lamacq. Thus, the eyeliner-wearing rhythm guitarist cemented a reputation that his lyrics about prostitution, the Holocaust and his own eating disorders could only augment. The Manic Street Preachers’

The Holy Bible

(1994) is considered by many the most harrowingly personal UK rock album since Joy Division’s

Closer

- a catharsis via Edwards’s notebooks - the song ‘4st 7lb’ in particular a reminder of the worsening condition of its author. Just days after the album’s release, he’d checked himself into The Priory; in the months that followed, he shaved his head and dressed as a concentration camp victim.

Then, on 1 February 1995, Edwards (who’d briefly gone AWOL from tour duty the previous summer) checked out of London’s Embassy Hotel at 7 am, ahead of the band’s flight to America. All that was left behind was a note reading simply: ‘I love you.’ Although there’s evidence that he returned to his Cardiff flat, Edwards’s whereabouts from this moment cannot be ascertained. Unconfirmed sightings of the musician occurred regularly over the next fortnight, while nearly £3K was withdrawn from his account - and, significantly, the majority of his notebooks were thrown into a river. David Cross, a young man with a mutual friend, claimed to have held Edwards in conversation at Newport bus station and cab-driver Anthony Hatherhall later told how a young man fitting the guitarist’s description took a random journey with him through the Welsh valleys. Hatherhall supposedly dropped his passenger at the Severn Bridge, where Edwards’s silver Vauxhall Cavalier was discovered on 14 February. Since then, identification of dredged-up remains as his has been dismissed, as have the majority of reported sightings as far afield as Brighton and Fuerteventura.

‘It does not enter my mind - and never has done. I am stronger than that.’

Richey Edwards, on suicide

Richey Edwards once spoke of the perfect disappearance - perhaps as escape, perhaps because he wanted to be sought or at least talked about. Whether he’s alive or not, he has achieved these objectives quite spectacularly.

Kramer was the son of Ohio scientist Ray Kramer, a professor of electrical engineering at Youngstown State. It was clear he had inherited his father’s prowess when, at the age of twelve, Philip Kramer won top prize at a local science fair, having built a laser powerful enough to burst a balloon. Kramer taught himself guitar at much the same time, quickly forming a garage band (the appropriately named Concepts) and then a Carpenters-style duo with his sister Kathy before he was twenty. When this did not yield the interest the young musician craved, he hit the alternative scene with a rock group called Max with then-unknown Ohio native Stiv Bators (later of The Dead Boys) – during which time he was occasionally living rough. By 1973 a job as a prop builder with Warner Brothers had eventually put Kramer in touch with Ron Bushy – drummer and founder member of Iron Butterfly. Although the band had been defunct for two years, Bushy, Kramer and erstwhile Butterfly guitarist Erik Braunn decided to take them on the road once more. The response was so impressive that for two years Kramer’s bass and gruff vocal tones delivered Iron Butterfly standards like the 1968 enormo-hit ‘In-a-Gadda-da-Vida’ to appreciative fans who’d never really gone away. Kramer whiled away time on the tour bus by scribbling illegible equations on hotel stationery – and, unlike most rock musicians, maintained fitness by completing 1,000 push-ups a day. After a couple of lukewarmly received new albums, however, the band split for a second time. When Gold, another band with Bushy, failed to ignite, Philip Kramer cut his losses and returned to scientific study Kramer had not completely finished working with rock stars: in 1990 he founded Total Multimedia, a computer company that pioneered compression software with his friend Randy Jackson (of The Jacksons). Despite early promise, the company was on shaky ground before it brought in former IBM executive Peter Olson to help turn its fortunes around. Olson, a proven name in the world of business technology, was also a huge subscriber to the then vastly popular

Celestine Prophecy,

James Redfield’s lifestyle compendium which spoke of ‘energy fields’ and ‘intuitive vibrations’. Those who did not buy into it dismissed the book as a hotchpotch of new-age clichés, but Olson believed in them wholeheartedly – and soon convinced Kramer, a man apparently grounded in hard scientific fact, about ‘beings of spiritual energy’. However, the more of this information the former musician assimilated, the more unsound his work practices became. By the beginning of 1995 colleagues were concerned by Kramer’s habit of working late and coming in to the office overflowing with some new hypothesis or other. By now he was concentrating on fractal and lightspeed theories – his father’s speciality; although the work was revolutionary in itself, Kramer had begun speaking in tongues, almost as if attempting to write his own sequel to Redfield’s thesis. The whole episode caused considerable unrest at Total Multimedia and the company fell into a downward spiral; eventually, Kramer’s co-directors convinced him that he would have to fire Olson. On the morning of 12 February, Kramer climbed into his 1993 Ford Aerostar van and, leaving his home near Thousand Oaks, drove to meet one of the directors at Los Angeles Airport to discuss a final resolution to the growing problem. Kramer failed to arrive. There was no sign of the van – and, as days and weeks passed by, no sign whatsoever of Philip ‘Taylor’ Kramer.

It was Philip Kramer’s immersion into the world of defence technology that led to the most serious conjectures about his disappearance. Kramer – who had found a niche in radar technology – had knowledge which was key to the design of the MX missile in Northrup, a project that he was working on at the time of his disappearance. Displaying the kind of glee normally reserved for tales of alien abduction or ‘Elvis is alive’ stories, the US media went into meltdown over this one – the way they saw it, kidnapping by a hostile foreign government was the most likely cause. There was a lot of support for this thinking: Ohio Democrat Representative James Traficant Jr requested FBI intervention – he believed Kramer and his father had hit upon a mathematical breakthrough and that the former could have been kidnapped in order for his extraordinary knowledge to be used for nefarious purposes. However, one or two clues that emerged soon after hinted at a more personal crisis. It transpired that Kramer had made seventeen cellphone calls that morning to his family and friends – an unusually high number for a businessman preparing to attend a routine meeting. Some messages expressed love, particularly that to his wife, Jennifer, and two children; a further message to Bushy spoke of ‘meeting again on the other side’. Finally, a noon 911 call surreally relayed how he believed O J Simpson was innocent – and, more significantly, how the musician himself planned to commit suicide.

For almost four and a half years, no evidence turned up. Finally, on 29 May 1999, amateur photographers chanced upon the well-hidden wreck of a Ford van and some skeletal remains at the foot of a ravine in Malibu, California – the vehicle and its occupant having plunged some 400 feet from the road above. Although it did not take long to ascertain that the bones were those of Philip Kramer, it was hard to fathom how this tragedy could have gone unnoticed in broad daylight – and whether Kramer actually took his own life remains unconfirmed.

See also

Stiv Bator(s) ( June 1990); Erik Braunn (Brann) (

June 1990); Erik Braunn (Brann) ( July 2003). Original Iron Butterfly singer Darryl DeLoach died in 2002.

July 2003). Original Iron Butterfly singer Darryl DeLoach died in 2002.