The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (298 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

Less than eighteen months after the passing of charismatic front man Danny Joe Brown ( March 2005)

March 2005)

came news of the death from natural causes of Molly Hatchet guitarist Duane Roland.

Brought up in Florida, Roland was the son of a concert pianist (his mother) and a guitarist (his father) but chose boogie-fuelled Southern rock as his own outlet. With Molly Hatchet, he enjoyed double-platinum success with the album

Flirtin’ with Disaster

(1979) and went on to become the owner of the group name, as the only member to appear on and co-write all of Hatchet’s records. Also performing with The Ball Brothers Band (pre-Hatchet) and The Dixie Jam Band (post-Hatchet), Roland had been married less than three years when he died.

Tuesday 20

Charles Smith

(Claydes Charles Smith - Jersey City, New Jersey, 6 September 1948)

Kool & The Gang

Charles Smith befriended a number of Jersey musicians in the late sixties, the bulk of whom were to stay with him as internationally acclaimed soul-funk unit Kool & The Gang. This extensive combo began life as The Jazziacs, the inspiration of brothers Ronald (tenor saxophone) and Robert ‘Kool’ Bell (bass). To the vocals of James ‘JT’ Taylor and the multi-instrumentation of Ricky West (Ricky Westfield, who died in 1985 – keyboards), Dennis ‘DT’ Thomas (sax), Robert Mickens (trumpet) and ‘Funky’ George Brown (drums) was added the playing and songwriting skills of Smith – whose hits cusped the parallel universes of the dance floor and the boudoir. Among the lead guitarist’s co-credits were the US chart-topper ‘Celebration’ (1980, UK Top Ten) and another million-selling hit in 1984’s ‘Joanna’, which made number two on both sides of the Atlantic.

While the sprawling line-up of Kool & The Gang was revised many times throughout the seventies and eighties, stalwart Charles Smith remained a key member during both phases of the band’s success and only stopped touring when poor health necessitated it in January 2006. Smith – who died from a lengthy illness at his Maplewood home – is survived by six children and nine grandchildren.

JULY

Friday 7

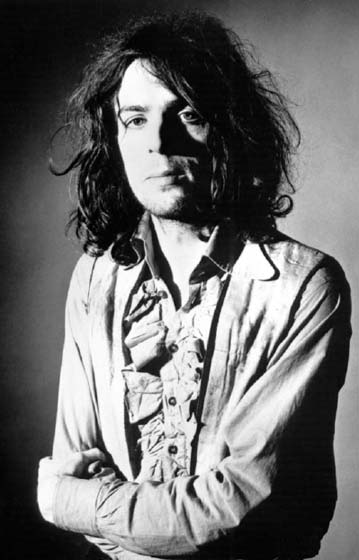

Syd Barrett

(Roger Keith Barrett - Cambridge, England, 6 January 1946)

Pink Floyd

(Stars)

His back catalogue of work can be documented in just a few seconds, but Syd Barrett – the ‘crazy diamond’ who opted

not

to shine under rock’s spotlight – still continues to make his presence felt within it. Following thirty years away from publicity, time finally caught up with the artist: Barrett desired recognition yet shied away from the typical rock star trappings – even the drugs that so damaged him were, first and foremost, a tool to the man.

One misapprehension that can be dissolved instantly is that Syd Barrett was ever diagnosed with any mental illness during his sixty years. As a boy, he seemed happy-go-lucky to most, interested in music and how to make it, and similarly fascinated with the art world’s mavericks, unaware that he himself was to use the former to join the latter’s ranks. Barrett suffered the loss of his encouraging, music-loving father during his mid-teens, but, with his talent already blossoming, had by then won the friendship and support of others – and had also soon acquired the name ‘Syd’, after local trad jazz drummer, Sid Barrett (the spelling alteration was to save confusion) – a name that was to last throughout his career. One of the songs that emerged from this prefame era was fan favourite ‘Effervescing Elephant’, a tune Barrett had apparently composed as a sixteen-year-old, and one that was to flag his remarkably literate character-based compositions.

Among those impressed was Cambridge school friend David Gilmour, who learned guitar with Barrett during lunch breaks. A few years later they found themselves busking in St Tropez, and the pair eventually became the creative hub of the embryonic Pink Floyd. Playing covers of old American R & B standards, the first line-up of the band – having decided on Syd’s suggested name (an amalgam of blues musicians Pink Anderson and Floyd Council) over The Tea Set – took up a residency at London’s new UFO Club, where their decidedly psychedelic take on traditional music started a whole new thing. Syd’s mirrored Telecaster and mesmeric readings of each tune proved a revelation. ‘The’ Pink Floyd – Barrett (guitar/vocals – replacing early singer Chris Dennis), Rado ‘Bob’ Klose (another school chum of Barrett’s – briefly lead guitar), Roger Waters (ex-Sigma 6 – bass/vocals), Richard ‘Rick’ Wright (ex-Sigma 6 – keyboards/wind) and Nick Mason (ex-Sigma 6 – drums) – were now managed by Peter Jenner, who in turn introduced them to producer Joe Boyd. From early studio sessions came the brilliant ‘Arnold Layne’ (1967), a typically witty Barrett song about a cross-dressing misfit apparently known to both him and Wright. This song secured Pink Floyd a deal with EMI and a UK Top Twenty hit.

Syd Barrett: Pity boy Floyd?

It was then that the guitarist hit the downward spiral that was to plumb frightening depths in the next few months. Barrett, thrust into the front and to some extent the public eye, was already showing signs of strain, according to his sister Rosemary Breen (with whom Barrett was always close), shunning his family and many of his friends. It was known that he’d been dropping newly fashionable psychedelics at his flat on London’s Cromwell Road – though band members today insist that these were foisted upon him by an increasing number of parasitic hangers-on. Barrett’s behaviour rapidly became so erratic that Wright ‘removed’ him to his Richmond home for the singer’s own good. The quality of his work was still in little doubt – the classic ‘See Emily Play’ (1967) took The Floyd high into the UK Top Ten – but Barrett was fast becoming unable to provide the necessary stamina to support the unit’s rising success. A key television performance of the hit was pulled, as were numerous tour dates, with the singer – who felt that this was ‘no longer art’ – making a habit of going AWOL when it was time to take the band on the road. (Wright, who also took Barrett away on holiday at this point, described him as burnt out, incapable of communicating and ‘always attempting to scale the walls’.). With a strong debut album

Piper at the Gates of Dawn

chockfull of Barrett tunes and needing no little live promotion, Gilmour was drafted as a second guitarist (and, eventually, singer) to cover for Barrett. Then, with a UK package tour alongside Amen Corner, The Nice and Jimi Hendrix descending into farce with the front man standing almost catatonic during shows and crucial American dates having to be scrapped, it was decided that Barrett was simply no longer up to it. The last song of his to make it onto a Floyd album was ‘Jugband Blues’ from 1968’s

Saucerful of Secrets.

By March of that year, Syd Barrett was effectively out of Pink Floyd.

By the end of the year, with the estranged singer sleeping on the floors of various friends, Gilmour and Jenner suggested to Barrett that he take time away and look to record his own material. The musician rallied somewhat and from this encouragement emerged

The Madcap Laughs

(1970), Barrett’s first solo effort – but one that owed much to the care of Gilmour and Waters, who ultimately had to salvage what were still fairly impenetrable musings, albeit with many slender threads of Barrett gold weaving their way through the mesh. A second album that year,

Barrett,

offered much of the same. Said Gilmour: ‘I could never understand how he could come up with all these wonderful songs, yet everyday life seemed such a struggle for him. I’m fairly sure he was on Mandrax when recording the album’.

By this time, Barrett had moved back to his mother’s house and was more often than not locking himself away to pursue his ‘other’ love – painting. His sister described a giant black canvas with nought but a tiny red square in one corner that led her to believe that her brother was still very much in trouble. Although his own recordings had not been met with the commercial approval of his previous band’s, Syd Barrett was still very much on the minds of many – not least Twink (John Alder, the ex-Pretty Things/Pink Fairies drummer, who attempted a shortlived band, Stars, with Barrett), his manager Jenner (who tried, unsuccessfully, to coax another album out of Barrett in 1974) and, of course, Pink Floyd themselves. The band, now globally accepted, based much of their meisterwerks

Dark Side of the Moon

(1973) and

Wish You Were Here

(1975) on their erstwhile singer’s difficult world. With Barrett ceasing all live appearances and effectively living as a hermit after 1972, it came as a huge shock to Floyd when their estranged friend showed up at Abbey Road during sessions for the latter album. Barrett, who was by now bloated and had shaven all of his body hair, went unrecognised for some time before Gilmour worked out his identity. Soon, the entire band – who by strange coincidence had been working on ‘Shine on You Crazy Diamond’, the record’s centrepiece and most direct tribute to Syd – realised who this shambling individual was, and it is said that Roger Waters was reduced to tears by the disclosure. According to Barrett’s sister, this could well have been a practical joke of Syd’s that backfired.

‘The brightest, wittiest and most popular guy I knew … but gradually he was not in the same world as you or I.’

David Gilmour

Thereafter, Barrett did his best to avoid any contact with Pink Floyd and indeed the outside world – only the occasional paparazzi photograph proved that he was still living in Cambridge. His obsession with art and his newfound love of gardening seemed to be keeping Barrett relatively happy, while Dave Gilmour ensured all royalties made it into his account. It’s felt, however, that he suffered another serious relapse around 1992 after the death of his mother – an event that saw Barrett destroy all his old diaries and memoirs and publicly chop up a garden fence. The year after, he flatly refused an offer of £75,000 from Atlantic to record again. Many began to believe that the former musician was suffering from a bipolar disorder, though this – like many of the tales that began to flourish about his private life – appears less than fully founded. Both Gilmour and Breen concur that experts insisted Barrett could not have been cured of any ailment, the latter also refusing to accept that he’d become a ‘recluse’, suggesting, not unreasonably, that this was merely fans ‘projecting their own disappointment’ onto the man.