The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (5 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

FIGURE 5.

Civilian Unemployment, Official vs. Shadowstats, 2000–2010 (Seasonally

Adjusted).

The SGS-Alternate Unemployment Rate reflects current unemployment reporting methodology adjusted for the significant portion of “discouraged workers” no longer included after 1994. The Bureau of Labor Statistics U-6 rate includes both discouraged workers as currently defined (discouraged less than one year) and long-term discouraged workers (discouraged more than one year). Source: Shadow Government Statistics, American Business Analytics and Research LLC,

shadowstats.com

.

FIGURE 6.

World Population Growth, 1000–2010.

Source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, “World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision” (2009–10 population data based on 2008 projection).

The Peak Oil Scenario

As mentioned, this book will argue that global economic growth is over because of a convergence of three factors — resource depletion, environmental impacts, and systemic financial and monetary failures. However, a single factor may be playing a key role in bringing the age of expansion to a close. That factor is oil.

Petroleum has a pivotal place in the modern world — in transportation, agriculture, and the chemicals and materials industries. The Industrial Revolution was really the Fossil Fuel Revolution, and the entire phenomenon of continuous economic growth — including the development of the financial institutions that facilitate growth, such as fractional reserve banking — is ultimately based on ever-increasing supplies of cheap energy.

Growth requires more manufacturing, more trade, and more transport, and those all in turn require more energy. This means that if energy supplies can’t expand and energy therefore becomes significantly more expensive, economic growth will falter and financial systems built on expectations of perpetual growth will fail.

As early as 2000, petroleum geologist Colin Campbell discussed a Peak Oil impact scenario that went like this.

14

Sometime around the year 2010, he theorized, stagnant or falling oil supplies would lead to soaring and more volatile oil prices, which would precipitate a global economic crash. This rapid economic contraction would in turn lead to sharply curtailed energy demand, so oil prices would then fall; but as soon as the economy regained strength, demand for petroleum would recover, prices would again soar, and as a result of that the economy would relapse. This cycle would continue, with each recovery phase being shorter and weaker, and each crash deeper and harder, until the economy was in ruins. Financial systems based on the assumption of continued growth would implode, causing more social havoc than the oil price spikes would themselves directly generate.

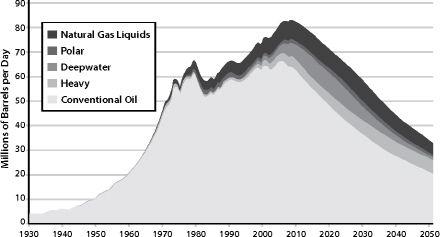

FIGURE 7.

World Oil Production.

Source: Colin Campbell, personal comunication.

Meanwhile, volatile oil prices would frustrate investments in energy alternatives: one year, oil would be so expensive that almost any other energy source would look cheap by comparison; the next year, the price of oil would have fallen far enough that energy users would be flocking back to it, with investments in other energy sources looking foolish. But low oil prices would discourage exploration for more petroleum, leading to even worse fuel shortages later on. Investment capital would be in short supply in any case because the banks would be insolvent due to the crash, and governments would be broke due to declining tax revenues. Meanwhile, international competition for dwindling oil supplies might lead to wars between petroleum importing nations, between importers and exporters, and between rival factions within exporting nations.

In the years following the turn of the millennium, many pundits claimed that new technologies for crude oil extraction would increase the amount of oil that can be obtained from each well drilled, and that enormous reserves of alternative hydrocarbon resources (principally tar sands and oil shale) would be developed to seamlessly replace conventional oil, thus delaying the inevitable peak for decades. There were also those who said that Peak Oil wouldn’t be much of a problem even if it happened soon, because the market would find other energy sources or transport options as quickly as needed — whether electric cars, hydrogen, or liquid fuel made from coal.

In succeeding years, events appeared to be supporting the Peak Oil thesis and undercutting the views of the oil optimists. Oil prices trended steeply upward — and for entirely foreseeable reasons: discoveries of new oilfields were continuing to dwindle, with most new fields being much more difficult and expensive to develop than ones found in previous years. More oil-producing countries were seeing their extraction rates peaking and beginning to decline despite efforts to maintain production growth using high-tech, expensive extraction methods like injecting water, nitrogen, or carbon dioxide to force more oil out of the ground. Production decline rates in the world’s old, super-giant oilfields, which are responsible for the lion’s share of the global petroleum supply, were accelerating. Production of liquid fuels from tar sands was expanding only slowly, while the development of oil shale remained a hollow promise for the distant future.

15

From Scary Theory to Scarier Reality

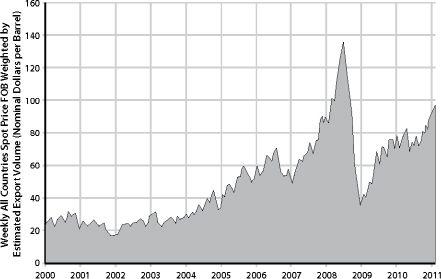

Then in 2008, the Peak Oil scenario became all too real. Global oil production had been stagnant since 2005 and petroleum prices had been soaring upward. In July 2008, the per-barrel price shot up to nearly $150 — half again higher (in inflation-adjusted terms) than the price spikes of the 1970s that had triggered the worst recession since World War II. By summer 2008, the auto industry, the trucking industry, international shipping, agriculture, and the airlines were all reeling.

FIGURE 8.

World Crude Oil Prices, 2000–2011.

Source: US Energy Information Administration.

But what happened next riveted the world’s attention to such a degree that the oil price spike was all but forgotten: in September 2008, the global financial system nearly collapsed. The most frequently discussed reasons for this sudden, gripping crisis had to do with housing bubbles, lack of proper regulation of the banking industry, and the over-use of bizarre financial products that almost nobody understood. However, the oil price spike had also played a critical (if largely overlooked) role in initiating the economic meltdown.

16

In the immediate aftermath of that global financial near-death experience, both the Peak Oil impact scenario proposed a decade earlier and the

Limits to Growth

standard-run scenario of 1972 seemed to be confirmed with uncanny and frightening accuracy. Global trade was falling. The world’s largest auto companies were on life support. The US airline industry had shrunk by almost a quarter. Food riots were erupting in poor nations around the world. Lingering wars in Iraq (the nation with the world’s second-largest crude oil reserves) and Afghanistan (the site of disputed oil and gas pipeline projects) continued to bleed the coffers of the world’s foremost oil-importing nation.

17

Meanwhile, the dragging debate about what to do to rein in global climate change exemplified the political inertia that had kept the world on track for calamity since the early ’70s. It had by now become obvious to a great majority of people familiar with the scientific data that the world has two urgent, incontrovertible reasons to rapidly end its reliance on fossil fuels: the twin threats of climate catastrophe and impending constraints to fuel supplies. Yet at the landmark international Copenhagen climate conference in December 2009, the priorities of the most fuel-dependent nations were clear: carbon emissions should be cut, and fossil fuel dependency reduced,

but only if doing so does not threaten economic growth

.

Bursting Bubbles

As we will see in Chapters 1 and 2, expectations of continuing growth had in previous decades been translated into enormous amounts of consumer and government debt. An ever shrinking portion of America’s wealth was being generated by invention of new technologies and manufacture of consumer goods, and an ever greater portion was coming from buying and selling houses, or moving money around from one investment to another.

As a new century dawned, the world economy lurched from one bubble to the next: the emerging-Asian-economies bubble, the dot-com bubble, the real estate bubble. Smart investors knew that these would eventually burst, as bubbles always do, but the smartest ones aimed to get in early and get out quickly enough to profit big and avoid the ensuing mayhem.

If Peak Oil and other limits on resources were closing the spigots on growth in 2007–2008, the pain that ordinary citizens were experiencing seemed to be coming from other directions entirely: loss of jobs and collapsing real estate prices.

In the manic days of 2002 to 2006, millions of Americans came to rely on soaring real estate values as a source of income, turning their houses into ATMs (to use once more the phrase heard so often then). As long as prices kept going up, homeowners felt justified in borrowing to remodel a kitchen or bathroom, and banks felt fine making those loans. Meanwhile, the wizards of Wall Street were finding ways of slicing and dicing sub-prime mortgages into tasty collateralized debt obligations that could be sold at a premium to investors — with little or no risk! After all, real estate values were destined to just keep going up.

God’s not making any more

land

, went the truism.

Credit and debt expanded in the euphoria of easy money. All this giddy optimism led to a growth of jobs in construction and real estate industries, masking underlying ongoing job losses in manufacturing.

A few dour financial pundits used terms like “house of cards,” “tinderbox,” and “stick of dynamite” to describe the situation. All that was needed was a metaphoric breeze or rogue spark to produce a catastrophic outcome. Arguably, the oil price spike of mid-2008 was more than enough to do the trick.

But the housing bubble was itself merely a larger fuse: in reality, the entire economic system had come to depend on impossible-to-realize expectations of perpetual growth and was set to detonate. Money was tied to credit, and credit was tied to assumptions about growth. Once growth went sour in 2008, the chain reaction of defaults and bankruptcy began; we were in a slow-motion explosion.

Since then, governments have worked hard to get growth started again. But, to the very limited degree that this effort temporarily succeeded in late 2009 and 2010, it did so by ignoring the underlying contradiction at the heart of our entire economic system — the assumption that we can have unending growth in a finite world.