The Essential Book of Fermentation (48 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

5 or 6 green and black tea bags

3½ quarts cool filtered water

2 cups kombucha starter liquid

1 kombucha SCOBY

1.

Place the quart of water in a nonaluminum cooking pot and add the sugar. Turn the heat to high and stir occasionally until the sugar dissolves. When the water comes to a boil, reduce the heat to medium, add the tea bags, and boil for 15 minutes.

2.

Place the 3½ quarts of cool, filtered water into the brewing vessel. When the sweet tea is ready, let it cool for a few minutes, then remove the tea bags and pour the tea mixture into the brewing vessel. Let the liquid in the vessel return to room temperature. This last is critical, because liquid that’s too hot can kill the SCOBY.

3.

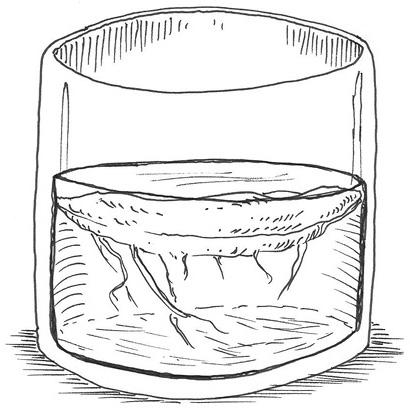

When the liquid is room temperature, add the kombucha starter liquid and SCOBY to the brewing vessel. The SCOBY may float, or it may sink; this makes no difference.

4.

Cover the vessel with the dish towel and clamp it securely to the outside of the vessel.

5.

Place the vessel in a warm (75 to 80ºF is ideal), airy, dark location. Do not disturb the brewing vessel for at least 5 days. No peeking in to see how it’s doing. Leave it alone.

6.

Bottle your kombucha following the directions below.

BOTTLING YOUR KOMBUCHA

After 5 to 7 days—the exact timing isn’t critical—uncover your brewing vessel and, using a straw, sip some of the fresh kombucha. It should taste and smell a little vinegary or sour and just slightly sweet. Once the batch turns slightly sour, you’ll want to bottle it in another day or two. Some sugar left in the kombucha is needed for the fermentation that will continue in the bottle, giving the brew that nice fizz. Try some store-bought kombucha to get an idea of the way you want your batch to taste, but remember, too much residual sugar will mean too much fizz and possibly exploding bottles, so just slightly sweet, please. If it tastes right to you, then it’s time to bottle. If it’s too sweet, let the fermentation proceed for as many days as it takes for the batch to taste right to you. If it’s too sour and vinegary, ferment the next batch for a shorter amount of time.

Let’s say you’re ready to bottle. You will have been collecting bottles and cleaning them thoroughly for a while. Grolsch beer bottles, with the attached stoppers, are perfect. So are glass kombucha bottles with caps that can be screwed down tightly. Some people use plastic bottles on the theory that if they do explode, they won’t send shards of glass flying, but I don’t trust the chemicals in the plastic in combination with the acidic kombucha—too much chance of chemicals leaching from the plastic into the drink. Beer bottles are great, but then you’ll need to go to your local beermaking shop for crown caps and a bottle capper, or order the same online. Just Google “crown caps and bottle cappers for sale.”

A common mistake that people make—especially new brewers—happens at bottling. And that is to mishandle the SCOBY, which, as we’ve learned, is a rather delicate conglomerate organism. So, before bottling, prepare a batch of sweet tea in a second glass, ceramic, or stainless-steel pot, minus only the SCOBY and the starter liquid. Uncover your brewing vessel. If there’s a film on top, that’s fine—it’s just another “mother” beginning to form. If, however, the film is fuzzy, like the mold you see on old bread, it most likely is mold and you’ll want to discard that batch and start again with more sanitary conditions.

Make sure your hands are perfectly clean. Using a plastic strainer—or your clean hands—lift the SCOBY from the brewing pot and immediately place it in the second pot of sweet tea. Now add the starter liquid to the SCOBY in its new batch of sweet tea. Take the starter liquid from the top of the kombucha, not from the bottom, or there will be too much yeast in it that can overwhelm your brew. You can brew this next batch in the second pot, or, after you’ve bottled the kombucha in the first pot, clean out the pot and transfer the fresh batch back into it.

You may notice some stringy filaments hanging below the SCOBY. These form naturally from the bacteria, yeast, and phenolics in the tea and are not dangerous.

Now is the time to add fruit juice, lemon juice, grated ginger, herb teas, or bits of dried fruit to the bottles to act as flavoring and to give the bottles a little extra sugar for the secondary fermentation that will make the fizz in the bottles. Don’t overdo the additions. A teaspoon of juice or fruit will flavor a 12-ounce bottle. Yes, dried fruit and grated ginger will give your kombucha some chewy bits, but they will be wholesome and easily swallowed. Use only 1 teaspoon of liquid flavoring if you want to avoid these extra bits. If you use a charge of white sugar, use only a scant ¼ teaspoon per 12-ounce bottle to avoid too much pressure in your bottles. To bottle, use a plastic funnel and fill the bottles to within ½ inch of the lip, then cap tightly.

WHO IS MAKING KOMBUCHA?

You are providing the conditions, but the SCOBY is actually turning sweet tea into kombucha. And who are the characters at play in the SCOBY? These are the main players, although there may be others.

Bacteria

Acetobacter spp.

Yeast

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

—Our old friend who makes our bread and our beer, among many other fermented foods.

Brettanomyces bruxellensis

—The bane of winemakers, since Brett, as they call it, gives an unwanted aroma to wine.

Candida stellata

—A yeasty fungus that once was classified as a

Saccharomyces.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe

—Much studied, it is a model organism in cellular microbiology. It grows from the ends of its rod-shaped body, then splits in the middle, yielding two cells from one, which is why it’s called the fission yeast.

Torulaspora delbrueckii

—This is the yeast that imparts banana and clove-like esters to German wheat beers.

Zygosaccharomyces bailii

—A spoilage yeast when it inhabits grape juice ferments, yet a beneficial partner when linked to its relatives in a SCOBY.

Place your bottles in a cardboard case kept at room temperature for 4 or 5 days after bottling, then put them in the fridge. If any bottles do explode, the cardboard case will contain the glass. Open your first bottle in the sink to make sure you don’t have too much fizz and soak the ceiling with kombucha.

Some of the kombucha sites recommend a continuous brewing method, using a rather expensive ceramic pot with a spigot. You can check out continuous brewing at www.kombuchakamp.com and at www.getkombucha.com. Both these sites are excellent and contain scads of information, including public posts where kombucha makers ask and answer questions.

Jun

And now, ladies and gentlemen, step into the inner tent of kombucha, the sanctum sanctorum, the holy of holies, where jun resides.

On one level, jun is green tea sweetened with honey and fermented by a jun mother, or SCOBY.

There seems to be a whole other level of jun, very romantic, mysterious, and secret. Emma Blue, writing on www.elephantjournal.com, titled her article “Jun: Nobody Wants Us to Know About It.” She says she has an anonymous source who first tasted jun in Tibet, at a camp at the base of Mount Kailash. “The rarest form of jun is Snow Leopard,” she says. “The Bonpo monks who produce this fine jun . . . were rumored to have been given heirloom cultures by Lao Tzu.

“The most easily found and tastiest jun in Tibet comes from the Khampa Nomads—former monks turned physical and spiritual warriors who learned how to make jun from the Bonpo. The Khampa Nomads were trained by the CIA in the 1970s to try to kick China out. They took jun so they would have superior fighting abilities against the Chinese. They are also guardians of heirloom cultures, travel on motorcycles with single long braids bouncing off their backs and flasks of jun and swords on their hips.”

I don’t know if I believe any of this, but someone should make a movie.

And there’s more. Jun is made, in secret, it appears, by Herbal Junction Elixirs in Oregon, because that firm will not divulge the recipe. Ms. Blue reports that people who have tasted Herbal Elixirs jun and Tibetan jun find they taste very similar, but “the jing in Tibetan jun is superior.” What is jing? “Jing is the thing that makes you levitate when you’ve got nothing to lose.”

She also says that her family knows a jun dealer who sells jun that he makes himself from a cooler in the back of his car. “Our jun dealer plays gongs for the jun while it brews, as he considers it a living sentient being and it will reprimand you for cursing around it. The first bottle is free.”

Again, I can’t separate fact from fiction, but I love the idea of an itinerant jun dealer who plays gongs for his ferment. Reminds me of the crazy hippie days.

Here in Sonoma County, the only jun I can find is made in Harbin in Lake County and sold at either Oliver’s Market or the Community Market in Santa Rosa. This latter market, originally a health food co-op, has been on the scene for thirty years and stocks whatever you need for your alternative lifestyle. The jun is flavored with elderberry and damiana, this latter being a southwestern and Central American shrub whose flowers have been prized for their aphrodisiac properties, and subsequently banned in certain prudish states. But there’s nothing prudish about Harbin Hot Springs, near the jun producer, where those who take the waters usually let it all hang out.

I am not a true believer type. I take a more scientific, skeptical approach to wild claims. But I’ll say this about jun: Drinking it makes me want to drink more of it. The elderberry-damiana jun that flows from Harbin in Lake County down here to Sonoma is tasty, fizzy, exciting stuff. Jun—pronounced with the schwa vowel sound, as in the word “won” but with a bit of jing in the sound, somewhere between the sounds in “gin” and “run”—is the beating heart of the kombucha movement.

You can double, triple, quadruple, or in general make more jun, using this as the base recipe.

1 pint commercial jun

5 green tea bags

1 quart filtered water