The Essential Book of Fermentation (47 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

Thing one: cleanliness. Keep all your equipment scrupulously clean. It doesn’t have to be sterilized, but a good washing and rinsing and maybe a final splash with boiling water are good ideas.

For equipment, you’ll need a large—8-gallon at least—metal brew pot with a lid for boiling the wort (the basic brew before fermentation), plus a fermentation vessel like a ceramic crock or large metal pot that will hold 5 gallons of wort. You’ll need a 5-gallon glass or food-grade plastic carboy, of the kind used on water coolers. You’ll need a rubber stopper with a hole in the center to fit the top of the carboy. A 5-to 6-foot length of plastic tubing will be needed to siphon the liquid from the boiling kettle to the fermentation tank. You’ll need an airlock to go into the stopper’s center hole in order to keep air away from the young beer before bottling. You’ll also need a hydrometer, a device that measures the relative density (what used to be called specific gravity) of a liquid. A scale that measures ounces is useful. And when it comes to bottling, you’ll need a funnel, beer bottles (duh), crown cap blanks, and a crown capping device. None of these things is terribly expensive. Here’s the recipe:

Makes from 42 to 48 bottles, depending on how much liquid you lose in racking from one vessel to another

5 pounds dried malt extract (DME), light extract

2 pounds dried malt extract (DME), amber extract

1 ounce Columbus hop pellets

1 ounce Simcoe and 1 ounce Sterling hop pellets

2 teaspoons Irish moss

½ ounce Simcoe and ½ ounce Sterling hop pellets

American ale yeast #1272

½ ounce Simcoe and ½ ounce Columbus hop pellets

¾ cup priming sugar (corn sugar) for bottling

1.

Start with 5 gallons of the best water you can find, such as filtered water or spring water. Put it into the 8-gallon kettle and bring to a boil. Carefully add the malt extracts and 1 ounce of the Columbus hop pellets.

2.

After 35 minutes, add 1 ounce each of Simcoe and Sterling hop pellets.

3

At 45 minutes into the boil, add the Irish moss. This seaweed clarifies the wort and helps settle particulate matter.

4.

At 60 minutes, add ½ ounce each of the Simcoe and Sterling hop pellets, turn off the heat, and let the kettle’s contents settle for 30 minutes. The hops, proteins, and solids will fall to the bottom of the kettle.

5.

Carefully siphon the clear liquid from the kettle into the fermentation tank. Use the hydrometer to measure the relative density. It should be about 1062.

6.

When the liquid is cool, mix the yeast in a cup of the young beer until it dissolves. Add the yeast slurry to the fermentation tank and stir it in well. Cover the fermentation tank with a clean towel or lid, if it has one. Clean out the brew pot and set it aside.

7.

The length of time of the fermentation will vary by temperature, so let the fermentation proceed until there is only minor bubble formation and the hydrometer now reads about 1012. This can take anywhere from 3 to 8 days, depending on the temperature. Let your hydrometer reading be your guide.

8.

Add ½ ounce Simcoe and ½ ounce Columbus hop pellets to the carboy, then use the plastic tubing to siphon the fermented wort into the carboy. Fix the rubber stopper with the airlock into the top of the carboy and set the carboy in a cool (68ºF is ideal), dark spot for 2 weeks.

9.

Carefully siphon the ale into a clean large vessel such as your brew pot, leaving the residual yeast and sediment in the carboy. Add the priming sugar to the ale in the brew pot and stir well until entirely dispersed. Use the plastic tubing to fill beer bottles to about an inch from the top and crown cap the bottles. Put the bottles in cases and set aside for 2 weeks, during which time the corn sugar will referment in the bottles, adding the fizz. For better flavor maturation, wait 2 more weeks before drinking. Chill the bottles well before opening.

Making Kombucha

Ah, the fermented tea we call kombucha—so expensive and fizzilicious from the store, yet so inexpensive to make yourself at home. It’s not complicated to make, but it does take some time and can be sort of messy. The trick is to think it through before you set to work so that you avoid mistakes.

Making kombucha is a form of fermentation of sugar to alcohol, performed by the yeast components of the symbiotic combination of bacteria and yeast—the SCOBY. So although you start with a lot of sugar in your sweet tea, the finished product has less than a teaspoon of sugar in a gallon of kombucha and about one-fifth the calories of a can of soda pop.

But doesn’t turning all that sugar into alcohol mean that kombucha is strongly alcoholic, like wine or beer? No—because there are also bacteria in that SCOBY, mostly strains of acetic acid bacteria, especially the genus

Acetobacter,

that oxidize the ethanol alcohol to acetic acid, the compound that imparts the familiar tart taste and smell to vinegar. Finished kombucha has between 0.5 and 1.0 percent alcohol. That was enough for the federal government to pull kombucha off the shelves for being mislabeled a while back, but cooler heads prevailed and it was soon returned to the shelves. One would have to drink a prohibitively large amount of kombucha to get an alcohol buzz.

So you start making kombucha by making a sweet tea from sugar and a mixture of black and green teas. Some people wonder about all the caffeine in the black tea, but not to worry. Finished kombucha contains only about a quarter of the caffeine of regular black tea. That’s because the many strains of yeast and bacteria that are coexisting happily in the SCOBY exude enzymes that reduce caffeine to harmless substances. The fermentation from sweet tea to kombucha is marked by the major process of sugar to alcohol to acetic acid, but that’s just the most salient process. Many other enzymes and biologically active compounds are produced.

Unlike kefir, where we actually drink the healthful bacteria so they can colonize our gut, with kombucha the microbes stay in the mother, or mushroom, or, as we prefer to call it, the SCOBY, and we drink the goodness they create in the sweet tea.

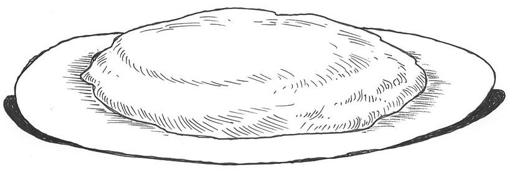

The SCOBY (symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast), shown here out of its vessel of sweet tea and resting on a platter, is a living organism, so the younger and fresher, the better.

The key to kombucha success is to begin with a healthy, fresh SCOBY. If you have a friend making kombucha, he or she may have one to give you. If not, they are available from many sources, including www.kombuchabrooklyn.com, www .culturesforhealth.com, and www.kombuchakamp.com. Remember that the culture is a living organism, so the younger, more alive, and fresher, the better. Never try to make kombucha from a culture that is dehydrated, has been stored in the fridge or stored in plastic for over thirty days, is moldy, puny, or mushy, or has disintegrating dark spots. It should be firm and healthy-looking, off-white in color, with the consistency of a piece of fresh calamari. Your culture will thrive if it’s fed what it likes and is cared for so it doesn’t dry out or become neglected. A SCOBY pet? Not a bad way to think about it.

The SCOBY may seem firm and healthy, but it’s a somewhat delicate pet. It thrives in glass, ceramic, porcelain, or stainless-steel vessels, but not in plastic—even food-grade plastic—or any other kind of metal vessel, especially aluminum. The pH of kombucha can get down to around 3.0, which is strongly acid, and the acidity can leach toxics from plastic and react with aluminum or any other metal except stainless steel. Don’t worry about putting acid in your stomach—it’s already full of gastric juice, primarily hydrochloric acid with a pH of 2.0. Your tummy loves acidity. After all, those yogurt-making microbes are called

Lactobacillus acidophilus

(acid-loving) and they like living in your intestines, as well as fermenting your vegetables, krauts, and kimchi.

You can use an organic Sucanat if you wish, but there are elements in those “whole juice” sugars that may slow the fermentation. White, granulated cane sugar is fine, since it is entirely sucrose and is almost all converted during the primary fermentation or secondary fermentation in the bottle (giving the kombucha that lovely fizz). Use no other sweetener for kombucha—that means no honey, no agave sugar, no stevia, and for goodness’ sake, no artificial sweeteners like aspartame. The SCOBY wants good old sucrose, period.

For the sweet tea, use only green tea and black tea (but not Earl Grey, which has been doused with the essential oil of bergamot, which your SCOBY will not like). No herb teas, tisanes, or flavorings at this stage. You can add flavorings and herbal decoctions, but only at bottling, after the kombucha has been made. Just be patient and we’ll get there.

The only other ingredient in the sweet tea that will become kombucha is some already-made kombucha, the “starter liquid,” to make the SCOBY feel at home and encourage it in certain directions. If this is your first batch, borrow some unflavored kombucha from a friend or ask on www.fermentersclub.com if someone near you has some unflavored kombucha to spare. Or you can buy a bottle of unflavored kombucha at the market and pour it into a bowl to allow it to go flat, then use it as a starter liquid. Just make sure it isn’t flavored. The bottler may have it labeled “Original,” but read the ingredients carefully.

Okay, you have your SCOBY, sugar, filtered water, green and black tea bags (5 or 6 in all), starter liquid, and a proper brewing vessel that will easily hold a gallon or more (a 2-gallon vessel is best). You’ll also need a clean dish towel to cover the brewing vessel—no cheesecloth; its weave is too loose and the fruit flies that will be attracted to your vessel as the kombucha is fermenting may be able to get in. A linen dish towel is best, but any tightly woven towel will do. And you’ll need a large rubber band or some way to clamp the towel tightly around the vessel. I have used several long twist ties twisted together. They work fine. If you can tie string tightly enough around the vessel, that will work, too.

Your vessels should be freshly washed and perfectly clean, and so should your hands. Some brewers finish hand washing by pouring filtered water over their hands, then drying them on a fresh, clean dish towel or paper towel. Others dip their hands in white vinegar. Whatever. Strive for cleanliness.

After you’ve set up the brewing vessel with sweet tea, SCOBY, and starter liquid, you will need to find a place that’s warm for a proper fermentation to occur. At 75 to 80ºF, the fermentation should take from 5 to 7 days. At colder temperatures, it can take 2 weeks, or even stop altogether. You may want to set a heating pad on the lowest setting in a location where you want the brewing to take place, put a large jar or pot of water on it, and take the water temperature after 3 or 4 hours. If this test pot is in the 75 to 80ºF range, your brewing vessel will be good to go in that spot. If it’s warmer than 80ºF, you may have to adjust the position of the test pot above the heating pad—like setting it up on a footstool—until you get the right temperature. With a heating pad, it’s unlikely your test pot will be cooler than 70ºF, which is low but still okay. Just make sure the heating pad is not covered by anything that could mean a heat buildup and fire.

Homemade Kombucha

1 quart filtered water

¾ cup granulated sugar