The Everything Mafia Book (21 page)

Law enforcement officials had been trying for years to identify the heads of the big Mafia families. They wanted to get a handle on the secret society’s power structure and chain of command. The Mafia obliged them by gathering every major don under one roof. There is no existing agenda or itinerary of what was to be discussed at the meeting. Maybe it was the controversial drug-dealing dilemma. Perhaps it was the recent murder of Albert Anastasia and the bungled hit on Frank Costello. None of the gentlemen in attendance deigned to discuss the affair. They probably did not have a chance to discuss much, since it ended rather abruptly.

Trouble Afoot

Joe Barbara did not know that he was under surveillance and had been for some time. He had received visits in the past from Joe Bonanno and others who the cops suspected were criminals. He also booked most of the hotel rooms in the small town of Apalachin. This raised a red flag for the state police.

Dons and assorted bodyguards and wise guys descended upon the sleepy little community. Goombahs in pinstriped suits flooding the area must have looked a little conspicuous in a land of cows and cornfields. The local police sensed something was afoot, and they alerted higher authorities. On November 14, 1957, four law enforcement officers pulled up to the house in two cars. The dons assumed it was a raid and scampered into the woods, $2,000 suits and all. Those who escaped by car were nabbed at roadblocks and became overnight guests of the New York State Police.

All of them maintained that they were paying a call on their sick friend Joe Barbara. Barbara himself told the law that it was a convention of salesmen from the Canada Dry soft drink company.

Joe Bonanno always maintained that he was not at the Apalachin meeting, but rather in a nearby town meeting with Buffalo mob boss Stefano Magaddino. When two of Joe’s men were driving near Barbara’s estate they were caught in the state trooper roadblock. Joe stated that one of his men had Joe’s driver’s license, and that’s why they said Joe Bonanno was at Apalachin.

The names of those detained is a Who’s Who of hoodlums: Carlo Gam-bino, Paul Castellano, Tommy Lucchese, Joe Profaci, Joe Colombo, Vito Genovese, Frank Costello, Tony Accardo, Santo Trafficante Jr., Carlos Marcello, and Sam Giancana. There were also numerous representatives from lesser families, like James “Black Jim” Colletti from Pueblo and Russell Bufalino from northeast Pennsylvania.

Believe it or not, none of the approximately sixty gangsters were arrested; they were only detained for questioning. So little was known about the shadowy Mafia in 1957 that the cops had no idea that they had in one fell swoop nabbed the most vicious and successful criminal kingpins in the country. The shadow life of the Mafia was over.

Apalachin Agenda

Several sources offer different reasons for why the meeting was called in the first place. Joe Valachi said it was a coming-out party for the new dons, including Carlo Gambino. They were also there to grant clemency to Vito Genovese for his role in the Anastasia murder. The Mad Hatter was so despised and feared that no one was particularly sorry to see him go.

The brother of the late and not especially lamented Anastasia, who went by the name Anastasio, said that the objective of the meeting was to decide which misbehaving mobsters and which intrusive federal agents were to be whacked. Still another theory is that the whole thing was designed to set up and embarrass Vito Genovese, and the police were made aware of the meeting. Genovese was sent to prison on drug charges less than a year later.

Apalachin Aftermath

The Mafia was no longer a badly kept secret or a word that was only uttered in a hushed, fearful whisper. Dons were on the covers of

Life

and

Look

magazines. The media was abuzz with all things Mafia, and even J. Edgar Hoover had to admit that it existed.

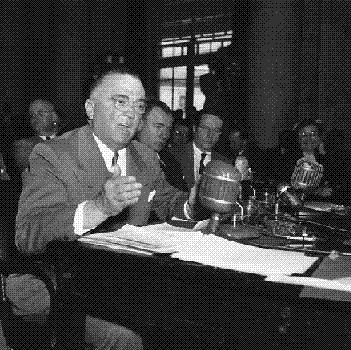

The FBI under the directorship of Hoover did very little to combat organized crime. Hoover steadfastly denied that there was a structured society of criminals who acted in unison to further their villainous goals. Hoover knew many reputed gangsters and was a big-time horseplayer. There were also the allegations that the mob knew about his cross-dressing predilection and blackmailed the G-man.

Public Opinions

Hoover and his beloved bureau took a lot of heat in the court of public opinion and from the politicians in Washington, DC. They wanted to know “what he knew and when he knew it,” as they say in Washington. And if Hoover did not know anything about the Mafia, Congress wanted to know why. Hoover engaged in some aggressive damage control with a program he called “the Top Hoodlum Program.” The FBI were playing catch-up with the Bureau of Narcotics, but they would eventually eclipse them in all-things Mafia.

The Top Hoodlum Program included wiretapping that was not the slightest bit legal but that garnered reels and reels of Mafia chatter. These tapes were inadmissible in a court of law but provided valuable information and insight into the underworld.

After the Apalachin blunder, the Mafia entered American popular culture as a subject of fascination, outrage, and revulsion. Never again would the activities of these ruthless and brutal men remain completely in the shadows. They were now as famous as they were infamous, and their world was no longer an inner sanctum of clandestine criminality. The law turned up the heat, and the public loved to read about their exploits and see movies about them. Mafiosi would do the unthinkable and break their sacred vow of Omerta. Newspapers across the country turned up the heat, leading some crusading reporters to take the gangsters, as well as the police, to task for not going after the illegal gambling and vice in their respective cities.

In cities like Tampa, grand juries were convened that brought dozens of criminals to the courthouse, where they were eagerly photographed for the headlines in the next morning’s newspaper. But for all this fleeting interest in the Mafia, little came of it in the ’40s and ’50s. In fact, it was another dozen years before the law began to make some inroads against the Mafia.

CHAPTER 11

Vegas, Baby, Vegas!

Las Vegas is also known as “Sin City,” and the place where if things happen, “they stay in Vegas.” It’s a carnal playground where you can indulge your deepest, darkest fantasies and maybe even make your fortune. The Mafia was a fixture in Vegas during its glitzy glory days and transformed it from a wild and woolly honky-tonk town to the entertainment capital of the world. Along the wild way, the Mafia fell from its lofty perch and was reduced to scrapping out meager bucks from low-level rackets while corporate suits raked in the big bucks.

Oasis in the Desert

Gambling casinos existed before the Mafia got to Las Vegas. Gambling was legalized in 1931 by the state of Nevada. The early casinos were more like rowdy honky-tonks and cowboy hangouts than the modern casinos that would soon spring up in the desolate wilderness. Who would have thought that a bunch of immigrant kids from New York’s Lower East Side would become the power brokers and robber barons in the Wild West? When the Mafia decided to “enter the western market” they sent an emissary to the Promised Land and, so the legend goes, he put Las Vegas on the map.

Bugsy

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel was a member of the New York mob. A Jewish kid from the mean streets of immigrant New York City, he was also a charismatic and good-looking guy who had ambitions to be a movie star. He was born in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, but cut his teeth running nickel-and-dime crap games and extorting pushcart operators on the Lower East Side, where he fell in with upcoming Jewish mobsters Meyer Lansky and Moe Sedway and moved into the lucrative bootlegging racket. It was all uphill from there for the young gagnster. Siegel strove to rise above the street-level thug image that was portrayed in the movies. He wanted to leave a legacy that would ensure his place in history.

Meyer Lansky is the most famous of the Jewish Mafia men and is considered one of the founding fathers of Las Vegas. Lesser-known but influential gangsters Moe Sedway and Dave Berman may not be household words, but they could also be on a Mount Rushmore of Vegas founders.

While most hoods kept a low profile, Siegel was one of the first of the celebrity gangsters. Tall, dark, and handsome, he became a darling of the Hollywood set, many of whom got a vicarious thrill from flirting with danger. Starlets who went for the “bad boy” type needed look no further than a psycho mobster murderer. Bugsy’s name came from his mercurial temperament and tendency to fly off into violent rages, which in the parlance of the underworld was called “going bugs.” He did not like the name but would prove its validity by pummeling the poor soul who called him “Bugsy” to his face.

“Bugsy”Siegel

Courtesy of AP Images

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel poses after apprehension in Los Angeles on April 17, 1941, in connection with an indictment returned in New York charging him with harbouring Louis “Lepke” Buchalter.

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel poses after apprehension in Los Angeles on April 17, 1941, in connection with an indictment returned in New York charging him with harbouring Louis “Lepke” Buchalter.