The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book (26 page)

Read The Everything Theodore Roosevelt Book Online

Authors: Arthur G. Sharp

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

10-3. D

10-4. B

10-5. True: Czolgosz assassinated McKinley on September 6, 1901. He was executed on October 29, 1901.

CHAPTER 11

TR’s First Term

“We demand that big business give the people a square deal; in return we must insist that when anyone engaged in big business honestly endeavors to do right he shall himself be given a square deal.” (Letter to Sir Edward Grey, November 15, 1913)

TR did not enter the White House with a specific agenda. He intended to follow McKinley’s policies and retain his personnel. His primary goal initially was to exercise his right and duty to do anything that “the needs of the nation demanded unless such action was forbidden by the Constitution or by the laws.” He did not waste time causing “to be done many things not previously done by the President and the heads of the departments”—some of which might not have been expected from a Republican president.

Newlands Act

Reclamation and forestry were two of TR’s first priorities when he assumed the presidency. He had gained an appreciation for reclamation and conservation in his days in the Badlands and as the governor of New York. The White House gave him the influence he needed to push conservation on a national scale.

One of the lessons he had learned was that the western part of the United States was never going to grow if it did not have adequate water. That had been made abundantly clear by John Wesley Powell when he began exploring the West shortly after the Civil War ended. He noted that after the winter snow melted and the spring rains ended, the region went into a dry period. That was an impediment to farming, ranching, and increasing the population.

John Wesley Powell, like TR, was a self-trained naturalist. Although he lost an arm while fighting for the Union during the Civil War, he embarked on rugged field trips throughout the West, including one expedition to explore the Grand Canyon in 1869. His findings were invaluable in mapping the West—and supplying its need for water.

Powell suggested that an extensive irrigation system was needed to provide the badly needed water, and he mapped locations for dams and irrigation projects. A lot of people agreed with him, especially after a series of droughts hit the West in the 1890s. But nobody acted to do anything about the situation until TR stepped in.

After McKinley’s death and before TR moved into the White House, two of the men with whom he had worked on conservation projects in New York state—Gifford Pinchot and Frederick Haynes Newell—presented him with plans for a national irrigation system in the West and the consolidation of the forest work of the government in the Bureau of Forestry. The plans intrigued the president, but he recognized that implementing them would be difficult.

Natural resources were not the focal point of the federal government at the turn of the twentieth century. Every project suggested was tied up in legalistic red tape. President Roosevelt was not a great fan of bureaucracy, so he looked for ways to do an end run around the people in charge of natural resources.

As he described the situation:

The relation of the conservation of natural resources to the problems of National welfare and National efficiency had not yet dawned on the public mind. The reclamation of arid public lands in the West was still a matter for private enterprise alone; and our magnificent river system, with its superb possibilities for public usefulness, was dealt with by the National Government not as a unit, but as a disconnected series of pork-barrel problems …

He set out to change that situation.

Talking to Congress

TR actively participated in drafting the reclamation bill to control what went into it and to prevent opponents from wrecking it by insisting on individual states’ rights over national interests. In the process, he signaled lawmakers and the rest of America that he was a “hands-on” president, and that he would become involved personally in issues near and dear to his heart.

TR’s first step was to tell Congress how vital the irrigation issue was in national interests. He did that in his first message to Congress on December 3, 1901. That same day several Western senators and congressmen formed a committee to draft a reclamation bill. The chief architect was Francis G. Newlands of Nevada, after whom the eventual bill was named.

It did not take long for Congress to pass a bill. On June 17, 1902, Congress passed “An Act Appropriating the receipts from the sale and disposal of public lands in certain States and Territories to the construction of irrigation works for the reclamation of arid lands.” (The official name explains why the bill became known as the Newlands Reclamation Act.)

The act set aside the proceeds of the disposal of public lands for the purpose of reclaiming waste areas of the West through irrigation and building new homes upon the land. The settlers were responsible for repaying the money the government appropriated for the projects.

The repayments could be reused as a revolving fund that was available continuously for any work done. Work began immediately.

Without the Newlands Act and the water it made available, much of the West could not have been settled. Only ten months into his presidency, TR had accomplished a major piece of legislation that had significant repercussions for the entire country, not just localized sections. That was a major departure from ordinary federal government operations.

Twenty-eight irrigation projects attributed to the Newlands Act began between 1902 and 1906. They involved more than 3 million acres and more than 30,000 farms. Many of the dams built were higher than any constructed previously across the globe. The dams fed main-line canals over 7,000 miles in total length and involved the construction of tens of thousands of culverts and bridges.

New Services and Names

Five years after the initial passage of the act, the secretary of the interior created the United States Reclamation Service within the United States Geological Survey to administer the program. That same year, the service was renamed the United States Bureau of Reclamation.

Not everybody was happy with TR’s reclamation project. Opponents argued that he had acted illegally and hastily without regard to costs or constitutionality of the law. Such criticisms would become as common during the rest of TR’s presidency as the rivers and creeks that irrigated the arid West at the turn of the century.

Mostly, though, opponents were upset that TR could turn bureaucratic red tape into legislation quickly. That was his style as president, and the Newlands Act was the first—but not the last—time he would do it.

TR Is Taken for a Ride

It was not often that anyone could take Theodore Roosevelt for a ride. But on August 22, 1902, he rode in a purple-lined Columbia Electric Victoria during a parade in Hartford, Connecticut. Twenty carriages followed behind.

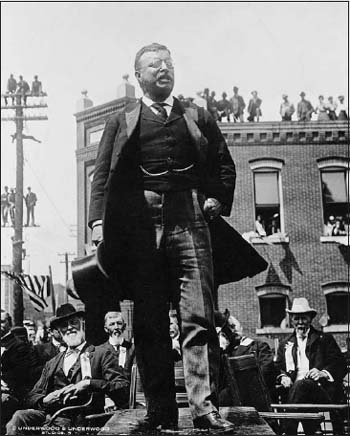

Theodore Roosevelt delivers speech in Hannibal, Missouri, 1903

Normally, the carriage—or simply a horse—would have been TR’s preferred mode of travel. But he always used a horse and carriage for official government purposes.

Technically, TR was not the first U.S. president to ride in an automobile. President McKinley rode in cars a couple times while in office, but never in public. Also, he was transported to a hospital in an electric ambulance after being shot. But TR holds the distinction of being the first U.S. president to ride in a car in public—and to own one as well.

Cars were just becoming part of the U.S. government’s travel fleet during TR’s second term in office. In 1907, the Secret Service started using two White Company steamers it borrowed from the army to transport visitors to and from the railroad station in Oyster Bay, where TR spent time in the summer.

There was no official appropriation for the use of these cars, but he did use them occasionally. Consequently, he became the first president to ride in a U.S. government automobile.

TR was more interested in enacting significant legislation and acting in the best interests of the American people than he was in establishing “firsts” as a president. That work continued.

The First Bird Reservation

Many of TR’s opponents believed his ideas and actions were for the proverbial birds. They were right to some extent. He was a great supporter of the preservation of birds and took steps as president to make sure they were protected.

TR believed that birds should be saved for utilitarian reasons, none of which had to do with money. He lamented the passage of birds like the passenger pigeon, which had been driven to extinction by habitat loss and over-hunting. So he acted to make sure that they were protected. His efforts to do so were nothing new for him.

When TR was governor of New York, making clothes and other articles of apparel with bird feathers was a common practice in the state. He expressed revulsion to the technique. As he emphasized, “Birds in the trees and on the beaches were much more beautiful than on women’s hats.” Since plume hunters were extremely busy in Florida, he decided to start his bird preservation activities there.