The Female Brain (7 page)

Authors: Louann Md Brizendine

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Psychology & Counseling, #Neuropsychology, #Personality, #Women's Health, #General, #Medical Books, #Psychology, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #Science & Math, #Biological Sciences, #Biology, #Personal Health, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Internal Medicine, #Neurology, #Neuroscience

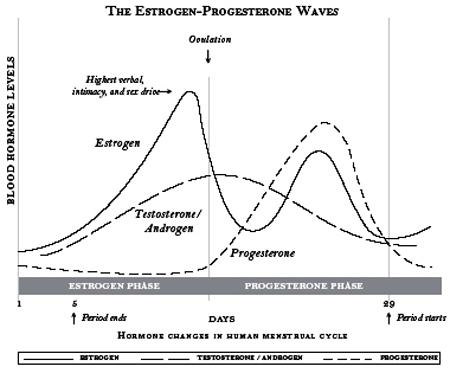

The smooth sailing of girlhood is over. Now parents find themselves walking on eggshells around a moody, temperamental, and resistant child. All of this drama is because the girlhood or juvenile pause has ended, and their daughter’s pituitary gland has sprung to life as the chemical brakes are taken off her pulsing hypothalamic cells, which have been held in check since toddlerhood. This cellular release sparks the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian system into action. It is the first time since infantile puberty that their daughter’s brain will be marinated in high levels of estrogen. In fact, it is the first time that her brain will experience estrogen-progesterone surges that come in repeated monthly waves from her ovaries. These surges will vary day to day and week to week.

The rising tide of estrogen and progesterone starts to fuel many circuits in the teen girl’s brain that were laid down in fetal life. These new hormonal surges assure that all of her female-specific brain circuits will become even more sensitive to emotional nuance, such as approval and disapproval, acceptance and rejection. And as her body blossoms, she may not know how to interpret the newfound sexual attention—are those stares of approval or disapproval? Are her breasts the right ones or the wrong ones? On some days her self-confidence is strong, and on other days it hangs by a precarious thread. As a child she was able to hear a wider spectrum of emotional tone in another’s voice than a boy could. Now that difference becomes even greater. The filter through which she feels the feedback of others also depends on where she is in her cycle—some days the feedback will reinforce her self-confidence, and other days it will destroy her. You can tell her one day that her jeans are cut a bit low and she’ll ignore you. But catch her on the wrong day of her cycle and what she hears is that you’re calling her a slut, or telling her she’s too fat to wear those jeans. Even if you didn’t say or intend this, it’s how her brain interprets your comment.

We know that many parts of the female brain—including an important seat of memory and learning (the hippocampus), the main center for control of the body’s organs (the hypothalamus), and the master center of emotions (the amygdala) are particularly affected by this new estrogen and progesterone fuel. It sharpens critical thinking and fine-tunes emotional responsivity. These enhanced brain circuits will stabilize into their adult shape by late puberty and into early adulthood. At the same time, we now know that the estrogen and progesterone surges start making the adolescent female brain, especially the hippocampus, experience weekly changes in sensitivity to stress that will continue until she passes through menopause.

Researchers at the Pittsburg Psychobiologic Studies Center studied normal seven-to sixteen-year-olds as they progressed through puberty, testing their stress responsivity and their daily levels of cortisol. The girls showed more intense responses, while boys’ stress responsiveness dropped. Females’ bodies and brains react to stress differently than do males’ once they have entered puberty. Fluctuating estrogen and progesterone in the brain is responsible for this opposite stress responsivity in the hippocampus of females. Males and females become reactive to different kinds of stress. Girls begin to react more to relationship stresses and boys to challenges to their authority. Relationship conflict is what drives a teen girl’s stress system wild. She needs to be liked and socially connected; a teen boy needs to be respected and higher in the male pecking order.

The girl’s brain circuits are arranged and fueled by estrogen to respond to stress with nurturant activities and the creation of protective social networks. She hates relationship conflict. Her brain’s stress response is massively triggered by social rejection. The ebb and flow of estrogen during the menstrual cycle changes this sensitivity to psychological and social stress on a weekly basis. The first two weeks of the cycle, when estrogen is high, a girl is more likely to be socially interested and relaxed with others. In the last two weeks of the cycle, when progesterone is high and estrogen is lower, she is more likely to react with increased irritability and will want to be left alone. Estrogen and progesterone reset the brain’s stress response each month. A girl’s self-confidence may be high one week but on thin ice the next.

During the juvenile pause of childhood, when estrogen levels are stable and low, a girl’s stress system is calmer and more constant. Once estrogen and progesterone levels climb at puberty, her responsivity to both stress and pain start to rise, all marked by new reactions in the brain to the stress hormone cortisol. She’s easily stressed, high-strung, and she starts looking for ways to chill out.

S

O

H

OW

D

OES

S

HE

C

ALM

D

OWN?

I was teaching a class of fifteen-year-olds about brain differences between males and females, and I asked the boys and girls to come up with some questions that they’d always wanted to ask each other. The boys asked, “Why do girls go to the bathroom together?” They assumed that the answer would involve something sexual, but the girls replied: “It’s the only private place at school we can go to

talk

!” Needless to say, the boys couldn’t ever imagine saying to another guy: “Hey, want to go to the bathroom together?”

That scene captures a pivotal brain difference between males and females. As we saw in Chapter 1, the circuits for social and verbal connection are more naturally hardwired in the typical female brain than in the typical male. It is during the teen years that the flood of estrogen in girls’ brains will activate oxytocin and sex-specific female brain circuits, especially those for talking, flirting, and socializing. Those high school girls hanging out in the bathroom are cementing their most important relationships—with other girls.

Many women find biological comfort in one another’s company, and language is the glue that connects one female to another. No surprise, then, that some verbal areas of the brain are larger in women than in men and that women, on average, talk and listen a lot more than men. The numbers vary, but on average girls speak two to three times more words per day than boys. We know that young girls speak earlier and by the age of twenty months have double or triple the number of words in their vocabularies than do boys. Boys eventually catch up in their vocabulary but not in speed or overlapping speech. Girls speak faster on average, especially when they are in a social setting. Men haven’t always appreciated that verbal edge. In Colonial America, women were put in the town stocks with wooden clips on their tongues or tortured by the “dunking stool,” held underwater and almost drowned—punishments that were never imposed on men—for the crime of “talking too much.” Even among our primate cousins, there’s a big difference in the vocal communication of males and females. Female rhesus monkeys, for instance, learn to vocalize much earlier than do males and use every one of the seventeen vocal tones of their species all day long, every day, to communicate with one another. Male rhesus monkeys, by contrast, learn only three to six tones, and once they’re adults, they’ll go for days or even weeks without vocalizing at all. Sound familiar?

And why do girls go to the bathroom to talk? Why do they spend so much time on the phone with the door closed? They’re trading secrets and gossiping to create connection and intimacy with their female peers. They’re developing close-knit cliques with secret rules. In these new groups, talking, telling secrets, and gossiping, in fact, often become girls’ favorite activities—their tools to navigate and ease the ups and downs and stresses of life.

I could see it in Shana’s face. Her mother was complaining that she couldn’t get her fifteen-year-old to concentrate on work, or even a conversation about school. Forget keeping her at the table for dinner. Shana had an almost drugged look sitting in my waiting room while she anticipated the next text message from her girlfriend Parker. Shana’s grades hadn’t been great, and she was becoming a bit of a behavior problem at school, so she wasn’t allowed to go over to her friend’s. Her mother, Lauren, had also denied her use of the cell phone and the computer, but Shana’s reaction to being cut off from her friends was so over the top—she screamed, slammed doors, and started wrecking her room—that Lauren relented and gave her twenty minutes per day on the cell phone to make contact. But since she couldn’t talk in private, Shana resorted to text messaging.

There is a biological reason for this behavior. Connecting through talking activates the pleasure centers in a girl’s brain. Sharing secrets that have romantic and sexual implications activates those centers even more. We’re not talking about a small amount of pleasure. This is huge. It’s a major dopamine and oxytocin rush, which is the biggest, fattest neurological reward you can get outside of an orgasm. Dopamine is a neurochemical that stimulates the motivation and pleasure circuits in the brain. Estrogen at puberty increases dopamine and oxytocin production in girls. Oxytocin is a neurohormone that triggers and is triggered by intimacy. When estrogen is on the rise, a teen girl’s brain is pushed to make even more oxytocin—and to get even more reinforcement for social bonding. At midcycle, during peak estrogen production, the girl’s dopamine and oxytocin level is likely at its highest, too. Not only her verbal output is at its maximum but her urge for intimacy is also peaking. Intimacy releases more oxytocin, which reinforces the desire to connect, and connecting then brings a sense of pleasure and well-being.

Both oxytocin and dopamine production are stimulated by ovarian estrogen at the onset of puberty—and for the rest of a woman’s fertile life. This means that teen girls start getting even more pleasure from connecting and bonding—playing with each other’s hair, gossiping, and shopping together—than they did before puberty. It’s the same kind of dopamine rush that coke or heroin addicts get when they do drugs. The combination of dopamine and oxytocin forms the biological basis of this drive for intimacy with its stress-reducing effect. If your teenage daughter is constantly talking on the phone or instant-messaging with her friends, it’s a girl thing, and it is helping her through stressful social changes. But you don’t have to let her impulses dictate your family life. It took Lauren months of negotiation to get Shana to sit through a family dinner without text-messaging the world. Because the teen girl’s brain is so well-rewarded for communication, it’s a tough habit for you to curb.

B

OYS

W

ILL

B

E

B

OYS

We know that girls’ estrogen levels climb at puberty and flip the switches in their brains to talk more, interact with peers more, think about boys more, worry about appearance more, stress out more, and emote more. They are driven by a desire for connection with other girls—and with boys. Their dopamine and oxytocin rush from talking and connecting keeps them motivated to seek out these intimate connections. What they don’t know is that this is their own special girl reality. Most boys don’t share this intense desire for verbal connection, so attempts at verbal intimacy with their male contemporaries can be met with disappointing results. Girls who expect their boyfriends to chat with them the way their girlfriends do are in for a big surprise. Phone conversations can have painful lulls while she waits for him to say something. The best she can often hope for is that he is an attentive listener. She may not realize he’s just bored and wants to get back to his video game.

This difference may also be at the core of the major disappointment women feel all their lives with their marriage partners—he doesn’t feel like being social, he doesn’t crave long talks. But it’s not his fault. When he is a teen, his testosterone levels begin soaring off the charts, and he “disappears into adolescence,” a phase used by one psychologist friend of mine to describe why her fifteen-year-old son never wants to talk to her anymore, takes refuge with his buddies in person or online gaming, and visibly cringes at the thought of a family dinner or outing. More than anything, he wants to be left alone in his room.

Why do previously communicative boys become so taciturn and monosyllabic that they verge on autistic when they hit their teens? The testicular surges of testosterone marinate the boys’ brains. Testosterone has been shown to decrease talking as well as interest in socializing—except when it involves sports or sexual pursuit. In fact, sexual pursuit and body parts become pretty much obsessions.

When I was teaching the class of fifteen-year-olds and it was time for the girls to ask their questions of boys, they wanted to know this: “Do you prefer girls who have a little hair or a lot of hair?” I thought they meant hairstyles, as in long hair versus a shorter cut. But I quickly realized that they were referring to the boys’ preference for a lot or a little pubic hair. The boys resoundingly responded “No hair at all.” So let’s not mince words here. Young teen boys are often totally, single-mindedly consumed with sexual fantasies, girls’ body parts, and the need to masturbate. Their reluctance to talk to adults comes out of magical thinking that grown-ups will read between their spoken lines and the look in their eyes and know that the subject of sex has taken them over, mind, body, and soul.