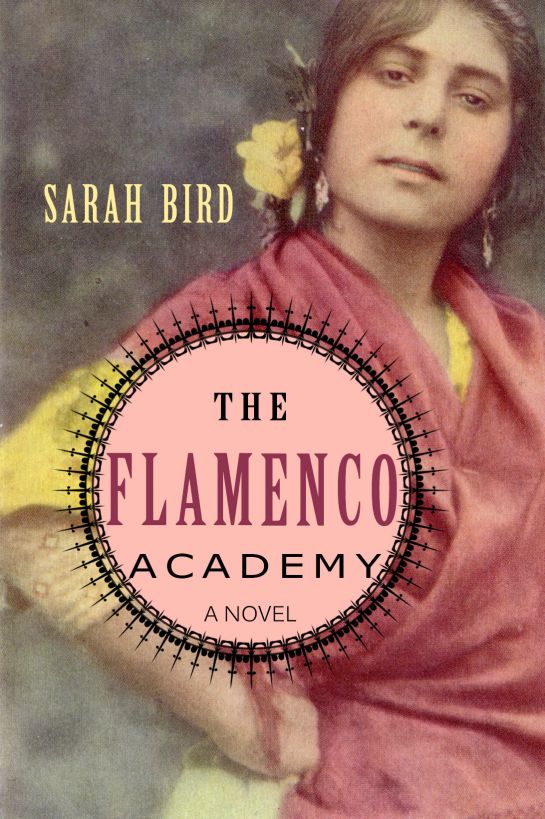

"The Flamenco Academy"

Read "The Flamenco Academy" Online

Authors: Sarah Bird

Tags: #fiction, #coming of age, #womens fiction, #dance, #obsession, #jealousy, #literary fiction, #love triangle, #new mexico, #spain, #albuquerque, #flamenco, #granada, #obsessive love, #university of new mexico, #sevilla, #womens friendship, #mother issues, #erotic obsession, #father issues, #sarah bird, #young adult heroines, #friendship problems, #balloon festival

The Flamenco Academy

To Greg Case, editor of

The Journal of Flamenco

Artistry

, August 23, 1945—July 11, 1998.

And to all true

flamencos

, past and

present.

First published by Random House, 2006

Copyright © Sarah Bird, 2006

EBook published by Sarah Bird at Smashwords, 2012

Copyright © Sarah Bird, 2012

Cover design by Gabriel Bird-Jones

EBook design by

A Thirsty Mind

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, without permission in writing from the author.

The Flamenco Academy

is a work of

fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products

of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any

resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead,

is entirely coincidental.

Table of Contents

In the green morning

I wanted to be a heart.

A heart.

And in the ripe evening

I wanted to be a nightingale.

A nightingale.

(Soul,

turn orange-colored.

Soul,

turn the color of love.)

In the vivid morning

I wanted to be myself.

A heart.

And at evening’s end

I wanted to be my voice.

A nightingale.

Soul,

turn orange-colored!

Soul,

turn the color of love!

—

Federico García Lorca

(1898-1936)

Flamenco has Ten Commandments. The first

one is:

Dame la verdad,

Give me the truth. The second is: Do

it

en compás,

in time. The third one is: Don’t tell

outsiders the rest of the commandments. I come here, to the edge of

the continent, to honor the first commandment, to give myself the

truth.

Waves, sparkling with phosphorescence in the

darkness, crash on the shore just beyond my safe square of blanket.

I cup my chilly hands around a mug of tea that smells of oranges

and clove and search for that first streak of salmon to crack the

far horizon. There might be one or two early risers, insomniacs,

troubled sleepers, who will see the light of a new day before me.

But not many. I am alone with my tea and my thoughts.

The waves roll in all the way from Asia

and slam against the shore. Their roar comforts me. It almost

drowns out the sound of heels, a dozen, two dozen, pounding on a

wooden floor, turning a dance studio into a factory manufacturing

rhythm. That is the ocean I hear. It is broadcast by the surge of

my own blood, pulsing

en compás,

in time, to a flamenco

beat. My heart beats and its coded rhythms force me to

remember.

Once upon a time, I stepped into a story

I thought was my own. It was not, though I became a character in it

and gave the story all the years it demanded from my life. The

story began long before I entered it, long before any of the living

and most of the dead entered it

.

I start on the night that I saw the greatest

flamenco dancer of all time perform. That night I had to decide

whose story my life would be about.

It was early summer in Albuquerque, when the

city rests between the sandblasting of spring winds and the

bludgeoning of serious summer heat to come. New foliage made a

green lace against the sky. The tallest trees were cottonwoods and

they spangled tender chartreuse hearts across the clouds. It was

the opening evening of the Flamenco Festival Internacional. A

documentary about Carmen Amaya, the greatest flamenco dancer ever,

dead now for forty years, was to be premiered at Rodey Theater on

the University of New Mexico campus.

I dawdled as I crossed the campus. The air

smelled like scorched newspaper. The worst forest fires in half a

century had been blazing out of control in the northern part of the

state. Four firefighters had already been killed and still the

fires moved south. That morning, the Archbishop of Santa Fe

announced that he would start saying a novena the next morning to

lead all the citizens of New Mexico in prayers for the rain needed

to save the state, to save our beloved

Tierra del

Encanto

.

I slowed my pace even more. I wanted to

reach the theater after the houselights were out so that I could

see as much of Carmen Amaya and as little of “the community” as

possible. I dreaded being plunged again into the hothouse world of

New Mexico’s flamenco scene. Tomorrow, when I started teaching, I

would have no choice. Tonight was optional and only the promise of

glimpsing the greatest flamenco dancer ever could have dragged me

out.

Although we, all us dancers, had studied

every detail of Carmen’s mythic life, although we had pored over

still photos and read descriptions of her technique, none of us had

ever seen her dance. Film footage of her dancing was so rare and so

expensive that we’d had to content ourselves with listening to the

legendary recordings she made with Sabicas. We memorized the

sublime hammer of her footwork, but hearing was a poor substitute

for seeing.

Only the news that the documentary contained

footage of Carmen Amaya performing could have gotten me out of my

bed and into the shower. The shower had removed the musty odor of

rumpled sheets and unwashed hair I’d wrapped myself in for the past

several weeks since I’d taken to wearing my own stink as

protection, as a way to mark the only territory I had left: myself.

I wouldn’t have been able to face the humiliation of seeing “the

community” at all if I hadn’t had my newly acquired secret to lean

on.

When I was certain that Rodey Theater would

be dark, I slipped in the back and grabbed the first empty seat.

Only there, alone and unseen, was it safe to take the secret out

and examine it. It strengthened me enough that I corrected my

slumped posture. I’d leaned on my new knowledge to get this far;

tomorrow, somehow, some way, the secret would guide me to what I

needed, what I had to have. Of course, tonight it changed nothing.

To everyone in the theater, which was every flamenco dancer,

singer, and guitarist in New Mexico, I was still the most pathetic

creature imaginable: the third leg of a love triangle.

The credits flickered; then Carmen Amaya’s

tough Gypsy face filled the screen, momentarily obliterating all

thoughts. It was brutal, devouring, the face of a little bull on a

compact body that never grew any larger or curvier than a young

boy’s. As taut with muscle as a python’s, that body had made Carmen

Amaya the dancer she was. A title beneath her face noted that the

year was 1935. She was only twenty-two, but had been dancing for

two decades.

She oscillated in luminous whites and inky

blacks, gathering herself in a moment of stillness, a jaguar

coiling into itself before exploding. A few chords from an unseen

guitarist announced an

alegrías

, Carmen’s famous

alegrías

. The audience, mostly dancers as avid as I, leaned

forward in their seats. Hiding from random gazes, I burrowed more

deeply into my chair, considered sneaking out. Even armed with my

secret, I wasn’t strong enough yet for this. There would be

questions, condolences, sympathy moistened with a toxic soup of

schadenfreude. I wasn’t ready to be a cautionary tale, the

ultra-pale Anglo girl who’d dared to fly too close to the flamenco

sun.

I was pushing out of my seat, about to

leave; then Carmen moved.

A clip from one of her early Spanish movies

played. The camera crouched low. Her full skirt whirled into

roller-coaster arcs that rose and plunged as those bewitched feet

hammered more rhythm into the world than any pair of feet before or

since. I dropped back into my seat, poleaxed by beauty as Carmen

told her people’s hard history in the sinuous twine of her hands,

the perfectly calibrated arch of her back, the effortless

syncopation of her feet.

I tore my eyes from the screen long enough

to pick out the profiles of other dancers, girls I’d studied with

for years, women who’d instructed us. They were rapt, mesmerized by

the jubilant recognition that Carmen Amaya was as good as her

legend. No, better. That not only was she the best back then, but

if she were dancing today none of us, forty years after her death,

could have touched her. I wished then that I were sitting with

those other pilgrims who’d made flamenco’s long journey, who

understood as I did just how good Carmen was.

I joined in the muttered benediction of

óles

, accent as always on the first syllable, that whispered

through the theater; then I surrendered and let Carmen Amaya’s

heels tap flamenco’s intricate Morse code into my brain. Though I

had willed it to never do so again, my heart fell back into

flamenco time and beat out the pulses with her. Flamenco flowed

through my veins once more. From the first, flamenco had been a

drug for me, an escape from who I was, as total as any narcotic,

and Carmen Amaya hit that vein immediately, obliterating despair,

rage, all emotion other than ecstasy at the perfection of her

dancing.

The brief clip ended. We all exhaled the

held breath and sagged back into our seats. An old-timer, white

shirt buttoned up to the top and hanging loosely about a corded

neck, no tie, battered, black suit jacket, appeared onscreen. A

subtitle informed us that he had once played guitar in Carmen’s

troupe.

“Tell us about Carmen’s family,” an

offscreen interviewer asked.

“

Gitana por cuatro costaos

,” the

guitarist answered. “Gypsy on four sides.” The translation of this,

the ultimate flamenco encomium, made my secret come alive and beat

within me. Blood, it was all about blood in flamenco.

The withered guitarist went on. “Carmen

Amaya was Gypsy on all four sides. We used to say that she had the

blood of the pharaohs in her veins back in the days when we still

believed that we Gypsies came from Egypt. We don’t believe that

anymore, but I still say it. Carmen Amaya had the blood of the

pharaohs in her veins. That blood gave her her life, but it also

killed her.”

“What do you mean?”

“Her kidneys. The doctor called it infantile

kidneys. They never grew any bigger than a little baby’s. La

Capitana only lived as long as she did because she sweated so much

when she danced. That was how her body cleansed itself. Otherwise,

she would have died when she was a child. Her costumes at the end

of a performance? Drenched. You could pour sweat out of her shoes.

She had to dance or die.”