The Flamingo’s Smile (34 page)

Read The Flamingo’s Smile Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Moreover, as his major experimental contribution, Just showed that the cell surface responded to fertilization as a continuous and indivisible entity, even though the sperm only entered at a single point. If the surface has such integrity, and if it regulates so many cellular processes, how can we meaningfully interpret the functions of cells by breaking them apart into molecular components?

Under the impact of a spermatozoon the egg-surface first gives way and then rebounds; the egg-membrane moves in and out beneath the actively moving spermatozoon for a second or two. Then suddenly the spermatozoon becomes motionless with its tip buried in a slight indentation of the egg-surface, at which point the ectoplasm develops a cloudy appearance. The turbidity spreads from here so that at twenty seconds after insemination—the mixing of eggs and spermatozoa—the whole ectoplasm is cloudy. Now like a flash, beginning at the point of sperm-attachment, a wave sweeps over the surface of the egg, clearing up the ectoplasm as it passes.

As his work progressed, Just claimed more and more importance for the cellular surface, eventually going too far. He wisely denied the reductionistic premise that all cellular features are passive products of directing genes in the nucleus, but his alternative view of ectoplasmic control over nuclear motions cannot be supported either. Moreover, his argument that the history of life records an increasing dominance of ectoplasm, since nerve cells are most richly endowed with surface material, and since brain size increases continually in evolution, reflects the common misconception that evolution inevitably yields progress measured by mental advance as a primary criterion. The following passage may reflect Just’s literary skill, but it stands as confusing metaphor, not enlightening biology:

Our minds encompass planetary movements, mark out geological eras, resolve matter into its constituent electrons, because our mentality is the transcendental expression of the age-old integration between ectoplasm and non-living world.

Finally, Just’s work also suffered because he had the misfortune to pursue his research and publish his book just before the invention of the electron microscope. The cell surface is too thin for light microscopy to resolve, and Just could never fathom its structure. He was forced to work from inferences based upon transient changes of the cell surface during fertilization—and he succeeded brilliantly in the face of these limitations. But within a decade of his death, much of his painstaking work had been rendered obsolete.

Thus, Just fell into obscurity partly because he claimed too much and alienated his colleagues, and partly because he knew too little as a consequence of limited techniques available to him. Yet the current invisibility of Just’s biology seems unfair for two reasons. First, he was basically right about the integrity and importance of cell surfaces. With electron microscopy, we have now resolved the membrane’s structure—a complex and fascinating story worth an essay in its own right. Moreover, we accept Just’s premise that the surface is no mere passive barrier, but an active and essential component of cellular structure. The most popular college text in biology (Keeton’s

Biological Science

) proclaims:

The cell membrane not only serves as an envelope that gives mechanical strength and shape and some protection to the cell. It is also an active component of the living cell, preventing some substances from entering it and others from leaking out. It regulates the traffic in materials between the precisely ordered interior of the cell and the essentially unfavorable and potentially disruptive outer environment. All substances moving between the cell’s environment and the cellular interior in either direction must pass through a membrane barrier.

Second, and more important for this essay, whatever the factual status of Just’s views on cell surfaces, he used his ideas to develop a holistic philosophy that represents a sensible middle way between extremes of mechanism and vitalism—a wise philosophy that may continue to guide us today.

We may epitomize Just’s holism, and identify it as a genuine solution to the mechanist-vitalist debate, by summarizing its three major premises. First, nothing in biology contradicts the laws of physics and chemistry; any adequate biology must conform with the “basic” sciences. Just began his book with these words:

Living things have material composition, are made up finally of units, molecules, atoms, and electrons, as surely as any non-living matter. Like all forms in nature they have chemical structure and physical properties, are physico-chemical systems. As such they obey the laws of physics and chemistry. Would one deny this fact, one would thereby deny the possibility of any scientific investigation of living things.

Second, the principles of physics and chemistry are not sufficient to explain complex biological objects because new properties emerge as a result of organization and interaction. These properties can only be understood by the direct study of whole, living systems in their normal state. Just wrote in a 1933 article:

We have often striven to prove life as wholly mechanistic, starting with the hypothesis that organisms are machines! Thus we overlook the organo-dynamics of protoplasm—its power to organize itself. Living substance is such because it possesses this organization—something more than the sum of its minutest parts…. It is…the organization of protoplasm, which is its predominant characteristic and which places biology in a category quite apart from physics and chemistry…. Nor is it barren vitalism to say that there is something remaining in the behavior of protoplasm which our physico-chemical studies leave unexplained. This “something” is the peculiar organization of protoplasm.

In striking metaphor, Just illustrates the inadequacy of mechanistic studies:

The living thing disappears and only a mere agglomerate of parts remains. The better this analysis proceeds and the greater its yield, the more completely does life vanish from the investigated living matter. The state of being alive is like a snowflake on a windowpane which disappears under the warm touch of an inquisitive child…. Few investigators, nowadays, I think, subscribe to the naïve but seriously meant comparison once made by an eminent authority in biology, namely that the experimenter on an egg seeks to know its development by wrecking it, as one wrecks a train for understanding its mechanism…. The days of experimental embryology as a punitive expedition against the egg, let us hope, have passed.

Third, the insufficiency of physics and chemistry to encompass life records no mystical addition, no contradiction to the basic sciences, but only reflects the hierarchy of natural objects and the principle of emergent properties at higher levels of organization:

The direct analysis of the state of being alive must never go below the order of organization which characterizes life; it must confine itself to the combination of compounds in the life-unit, never descending to single compounds and, therefore, certainly never below these…. The physicist aims at the least, the indivisible, particle of matter. The study of the state of being alive is confined to that organization which is peculiar to it.

Finally, I must emphasize once again that Just’s arguments are not unique or even unusual. They represent the standard opinion of most practicing biologists and, as such, refute the dichotomous scheme that sees biology as a war between vitalists and mechanists. The middle way is both eminently sensible and popular. I chose Just as an illustration because his career exemplifies how a thoughtful biologist can be driven to such a position by his own investigation of complex phenomena. In addition, Just said it all so well and so forcefully; he qualifies as an exemplar of the middle way under our most venerable criterion—“what oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed.”

This essay should end here. In a world of decency and simple justice it would. But it cannot. E.E. Just struggled all his life for judgment by the intrinsic merit of his biological research alone—something I have tried so uselessly (and posthumously) to grant him here. He never achieved this recognition, never came close, for one intrinsically biological reason that should not matter, but always has in America. E.E. Just was black.

Today, a black valedictorian at a major Ivy League school would be inundated with opportunity. Just secured no mobility at all in 1907. As his biographer, M.I.T. historian of science Kenneth R. Manning, writes: “An educated black had two options, both limited: he could either teach or preach—and only among blacks.” (Manning’s biography,

Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just

, was published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. It is a superbly written and documented book, the finest biography I have read in years. Manning’s book is an institutional history of Just’s life. It discusses his endless struggle for funding and his complex relationships with institutions of teaching and research, but says relatively little about his biological work per se—a gap that I have tried, in some respects, to fill with this essay.)

So Just went to Howard and remained there all his life. Howard was a prestigious school, but it maintained no graduate program, and crushing demands for teaching and administration left Just neither time nor opportunity for the research career that he so ardently desired. But Just would not be beaten. By assiduous and tireless self-promotion, he sought support from every philanthropy and fund that might sponsor a black biologist—and he succeeded relatively well. He garnered enough support to spend long summers at Woods Hole, and managed to publish more than seventy papers and two books in what could never be more than a part-time research career studded with innumerable obstacles, both overt and psychological.

But eventually, the explicit racism of his detractors and, even worse, the persistent paternalism of his supporters, wore Just down. He dared not even hope for a permanent job at any white institution that might foster research, and the accumulation of slights and slurs at Woods Hole eventually made life intolerable for a proud man like Just. If he had fit the mold of an acceptable black scientist, he might have survived in the hypocritical world of white liberalism in his time. A man like George Washington Carver, who upheld Booker T. Washington’s doctrine of slow and humble self-help for blacks, who dressed in his agricultural work clothes, and who spent his life in the practical task of helping black farmers find more uses for peanuts, was paraded as a paragon of proper black science. But Just preferred fancy suits, good wines, classical music, and women of all colors. He wished to pursue theoretical research at the highest levels of abstraction, and he succeeded with distinction. If his work disagreed with the theories of eminent white scientists, he said so, and with force (although his general demeanor tended toward modesty).

The one thing that Just so desperately wanted above all else—to be judged on the merit of his research alone—he could never have. His strongest supporters treated him with what, in retrospect, can only be labeled a crushing paternalism. Forget your research, deemphasize it, go slower, they all said. Go back to Howard and be a “model for your race” give up personal goals and devote your life to training black doctors. Would such an issue ever have arisen for a white man of Just’s evident talent?

Eventually, like many other black intellectuals, Just exiled himself to Europe. There, in the 1930s he finally found what he had sought—simple acceptance for his excellence as a scientist. But his joy and productivity were short-lived, as the specter of Nazism soon turned to reality and sent him back home to Howard and an early death.

Just was a brilliant man, and his life embodied strong elements of tragedy, but we must not depict him as a cardboard hero. He was far too fascinating, complex, and ambiguous a man for such simplistic misconstruction. Deeply conservative and more than a little elitist in character, Just never identified his suffering with the lot of blacks in general and considered each rebuff as a personal slight. His anger became so deep, and his joy at European acceptance so great, that he completely misunderstood Italian politics of the 1930s and became a supporter of Mussolini. He even sought research funds directly from II Duce.

Yet how can we dare to judge a man so thwarted in the land of his birth? Yes, Just fared far better than most blacks. He had a good job and reasonable economic security. But, truly, we do not live by bread alone. Just was robbed of an intellectual’s birthright—the desire to be taken seriously for his ideas and accomplishments. I know, in the most direct and personal way, the joy and the need for research. No fire burns more deeply within me, and no scientist of merit and accomplishment feels any differently. (One of my most eminent colleagues once told me that he regarded research as the greatest joy of all, for it was like continual orgasm.) Just’s suffering may have been subtle compared with the brutalization of so many black lives in America, but it was deep, pervasive, and soul destroying. The man who understood holism so well in biology was not allowed to live a complete life. We may at least mark his centenary by considering the ideas that he struggled to develop and presented so well.

HARRY HOUDINI

used his consummate skill as a conjurer to unmask legions of lesser magicians who masqueraded as psychics with direct access to an independent world of pure spirit. His two books,

Miracle Mongers and Their Methods

(1920) and

A Magician Among the Spirits

(1924), might have helped Arthur Conan Doyle had this uncritical devotee of spiritualism been as inclined to skepticism and dedicated to rationalism as his literary creation Sherlock Holmes. But Houdini campaigned a generation too late to aid the trusting intellectuals who had succumbed to a previous wave of late Victorian spiritualism—a distinguished crew, including the philosopher Henry Sidgwick and Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Darwin’s partner in the discovery of natural selection.

Wallace (1823–1913) never lost his interest in natural history, but he devoted most of his later life to a series of causes that seem cranky (or at least idiosyncratic) today, although in his own mind they formed a curious pattern of common thread—campaigns against vaccination, for spiritualism, and an impassioned attempt to prove that, even though mind pervades the cosmos, our own earth houses the universe’s only experiment in physical objects with consciousness. We are truly alone in body, however united in mind, proclaimed this first prominent exobiologist among evolutionists (see Wallace’s book

Man’s Place in the Universe: A Study of the Results of Scientific Research in Relation to the Unity or Plurality of Worlds

, 1903).

Wallace’s basic argument for a universe pervaded by mind is simple. I also regard it as both patently ill-founded and quaint in its failure to avoid that age-old pitfall of Western intellectual life—the representation of raw hope gussied up as rationalized reality. In short (the details come later) Wallace examined the physical structure of the earth, solar system, and universe and concluded that if any part had been built ever so slightly differently, conscious life could not have arisen. Therefore, intelligence must have designed the universe, at least in part that it might generate life. Wallace concluded:

In order to produce a world that should be precisely adapted in every detail for the orderly development of organic life culminating in man, such a vast and complex universe as that which we know exists around us, may have been absolutely required.

How could a man doubt that his favorite medium might contact the spirit of dear departed Uncle George when evidence of disembodied mind lay in the structure of the universe itself?

Wallace’s argument had its peculiarities, but one aspect of his story strikes me as even more odd. During the last decade, like the cats and bad pennies of our proverbs, Wallace’s argument has returned in new dress. Some physicists have touted it as something fresh and new—an escape from the somber mechanism of conventional science and a reassertion of ancient truths and suspicions about spiritual force and its rightful place in our universe. To me it is the same bad argument, only this time shorn of Wallace’s subtlety and recognition of alternative interpretations.

Others have called it the “anthropic principle,” the idea that intelligent life lies foreshadowed in the laws of nature and the structure of the universe. Borrowing the term from an opponent who used it for scorn, physicist Freeman Dyson proudly labels it “animism,” not because the idea is lively or organic but from the Latin

anima

, or “soul.” (Dyson’s essay, “The Argument from Design,” in his fine autobiography,

Disturbing the Universe

, provides a good statement of the argument.)

Dyson begins with the usual profession of hope:

I do not feel like an alien in this universe. The more I examine the universe and study the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense must have known that we were coming.

His defense is little more than a list of physical laws that would preclude intelligent life, were their constants just a bit different, and physical conditions that would destroy or debar us if they changed even slightly. These are, he writes, the “numerical accidents that seem to conspire to make the universe habitable.”

Consider, he states, the force that holds atomic nuclei together. It is just strong enough to overcome the electrical repulsion among positive charges (protons), thus keeping the nucleus intact. But this force, were it just a bit stronger, would bring pairs of hydrogen nuclei (protons) together into bound systems that would be called “diprotons” if they existed. “The evolution of life,” Dyson reminds us, probably “requires a star like the sun, supplying energy at a constant rate for billions of years.” If nuclear forces were weaker, hydrogen would not burn at all, and no heavy elements would exist. If they were strong enough to form diprotons, then nearly all potential hydrogen would exist in this form, leaving too little to form stars that could endure for billions of years by slowly burning hydrogen in their cores. Since planetary life as we know it requires a central sun that can burn steadily for billions of years, “then the strength of nuclear forces had to lie within a rather narrow range to make life possible.”

Dyson then moves to another example, this time from the state of the material universe, rather than the nature of its physical laws. Our universe is built on a scale that provides, in typical galaxies like our Milky Way, an average distance between stars of some 20 million million miles. Suppose, Dyson argues, the average distance were ten times less. At this reduced density, it becomes overwhelmingly probable that at least once during life’s 3.5-billion-year tenure on earth, another star would have passed sufficiently close to our sun to pull the earth from its orbit, thus destroying all life.

Dyson then draws the invalid conclusion that forms the basis for animism, or the anthropic principle:

The peculiar harmony between the structure of the universe and the needs of life and intelligence is a manifestation of the importance of mind in the scheme of things.

The central fallacy of this newly touted but historically moth-eaten argument lies in the nature of history itself. Any complex historical outcome—intelligent life on earth, for example—represents a summation of improbabilities and becomes thereby absurdly unlikely. But something has to happen, even if any particular “something” must stun us by its improbability. We could look at any outcome and say, “Ain’t it amazing. If the laws of nature had been set up just a tad differently, we wouldn’t have this kind of universe at all.”

Does this kind of improbability permit us to conclude anything at all about that mystery of mysteries, the ultimate origin of things? Suppose the universe were made of little more than diprotons? Would that be bad, irrational, or unworthy of spirit that moves in many ways its wonders to perform? Could we conclude that some kind of God looked like or merely loved bounded hydrogen nuclei or that no God or mentality existed at all? Likewise, does the existence of intelligent life in our universe demand some preexisting mind just because another cosmos would have yielded a different outcome? If disembodied mind does exist (and I’ll be damned if I know any source of scientific evidence for or against such an idea), must it prefer a universe that will generate our earth’s style of life, rather than a cosmos filled with diprotons? What can we say against diprotons as markers of preexisting intelligence except that such a universe would lack any chroniclers among its physical objects? Must all conceivable intelligence possess an uncontrollable desire to incarnate itself eventually in the universe of its choice?

If we return now to Wallace’s earlier formulation of the anthropic principle, we can understand even better why its roots lie in hope, not impelling reason. First, we must mention the one outstanding difference between Dyson’s and Wallace’s visions. Dyson has no objection to the prospect of intelligence on numerous worlds of a vast universe. Wallace upheld human uniqueness and therefore advocated a limited universe contained within the Milky Way galaxy and an earth impeccably designed, through a series of events sufficiently numerous and complex to preclude repetition elsewhere, for supporting the evolution of intelligent life. I do not know the deeper roots of Wallace’s belief, and I have little sympathy for psychobiography, but the following passage from his conclusion to

Man’s Place in the Universe

surely records a personal necessity surpassing simple inference from scientific fact. The preexisting, transcendent mind of the universe, Wallace writes, would allow only one incarnation of intelligence, for a plurality

…would introduce monotony into a universe whose grand character and teaching is endless diversity. It would imply that to produce the living soul in the marvellous and glorious body of man—man with his faculties, his aspirations, his powers for good and evil—that this was an easy matter which could be brought about anywhere, in any world. It would imply that man is an animal and nothing more, is of no importance in the universe, needed no great preparations for his advent, only, perhaps, a second-rate demon, and a third or fourth-rate earth.

This major difference in opinion about the frequency of intelligent life should not mask the underlying identity of the primary argument advanced by Wallace and by modern supporters of the anthropic principle: intelligent life, be it rare or common, could not have evolved in a physical universe constructed even a tiny bit differently; therefore, preexisting intelligence must have designed the cosmos. Wallace’s description of his supporters could well include Dyson: “They hold that the marvellous complexity of forces which appear to control matter, if not actually to constitute it, are and must be mind-products.”

Yet the universe used by Wallace to uphold the anthropic principle could not be more radically different from Dyson’s. If the same argument can be applied to such different arrangements of matter, may we not legitimately suspect that emotional appeal, rather than a supposed basis in fact or logic, explains its curious persistence? Dyson’s universe is the one now familiar to us all—awesome in extent and populated by galaxies as numerous as sand grains on a sweeping beach. Wallace’s cosmos was a transient product of what his contemporaries proudly labeled the “New Astronomy,” the first, and ultimately faulty, inferences made from a spectrographic examination of stars.

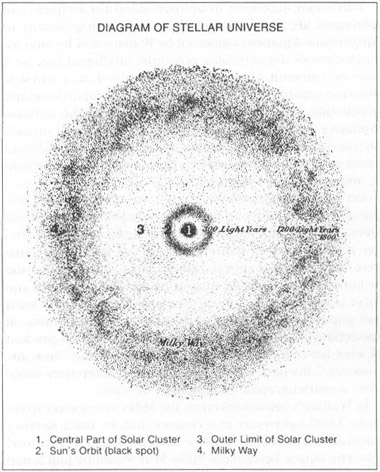

In Wallace’s limited universe, the Milky Way galaxy spans some 3,600 light-years in a cosmos that, by Lord Kelvin’s calculation, could not be more than twice as large in total diameter (space beyond the Milky Way would be populated by few, if any, stars). A small “solar cluster” of stars sits in the center of the universe; our own sun lies at or near its outer limit. A nearly empty region extends beyond the solar cluster, followed, at a radius of some 300 light-years from the center, by an inner ring of stars and other cosmic objects. Another and much larger region of thinly populated space lies beyond the inner ring, followed by a much larger, densely filled outer ring, the Milky Way proper, with a span of 600 light-years, and lying 1,200 to 1,800 light-years from the center.

Wallace’s version of the anthropic principle holds that life requires each part of this intricate physical universe, and that life could only arise around a sun situated where ours resides by good fortune, at the outer edge of the central solar cluster. All these rings, clusters, and empty spaces must therefore reflect the plan of preexisting intelligence.

A.R. Wallace’s universe, constructed with precision to make human life possible. See text for explanation.

FROM WALLACE,

1903.

REPRINTED FROM NATURAL HISTORY

.

Wallace’s argument requires that distant stars have a direct and sustaining influence upon our earth’s capacity to support life. He flirts with the idea that stellar rays may be good for plants as he desperately tries to argue around a contemporary calculation that the bright star Vega affords the earth about one 200-millionth the heat of an ordinary candle one meter distant. He even advances the dubious argument that since stars can impress their light upon a photographic plate, plants may also require the same light to carry out their nighttime activities—quite a nimble leap of illogic from the fact that film can

record

to the inference that living matter

needs

.

But Wallace didn’t press this feeble, speculative argument. Instead, he emphasized that life depends upon the detailed physical structure of the universe for the same reason that Dyson cites in his two major examples: the evolution of complex, intelligent life requires a central sun that can burn steadily for untold ages, and such stable suns develop only within a delicate and narrow range of physical laws and conditions. Dyson emphasizes stellar density and diprotons; Wallace argued that appropriate suns could only exist in a universe structured like ours and only at the edge of a central cluster in such a universe.

In Wallace’s universe, stars are concentrated in three regions: the outer ring (or Milky Way proper), the inner ring surrounding the central cluster, and the central cluster itself. The outer ring of the Milky Way is too dense and active a region for stable suns. Stars move so rapidly and lie so close to each other that collisions and near approaches will inevitably disrupt any planetary system before intelligent life evolves.