The Foremost Good Fortune

Read The Foremost Good Fortune Online

Authors: Susan Conley

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2011 by Susan C. Conley

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A.

Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada

by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Conley, Susan, [date].

The foremost good fortune / by Susan Conley.—1st ed.

p. cm.

“This is a Borzoi Book”—T.p. verso.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59520-1

1. Conley, Susan. 2. Conley, Susan —Family.

3. Conley, Susan, 1967– —Health. 4. Beijing (China)—Biography.

5. Beijing (China)—Social life and customs. 6. Americans—

China—Beijing—Biography. 7. Cancer—Patients—China—

Beijing—Biography. 8. Cancer—Treatment—China—Beijing.

9. Portland (Me.)—Biography. I. Title.

DS795.23.C66A3 2010

951′.15606092—dc22

[B] 2010036000

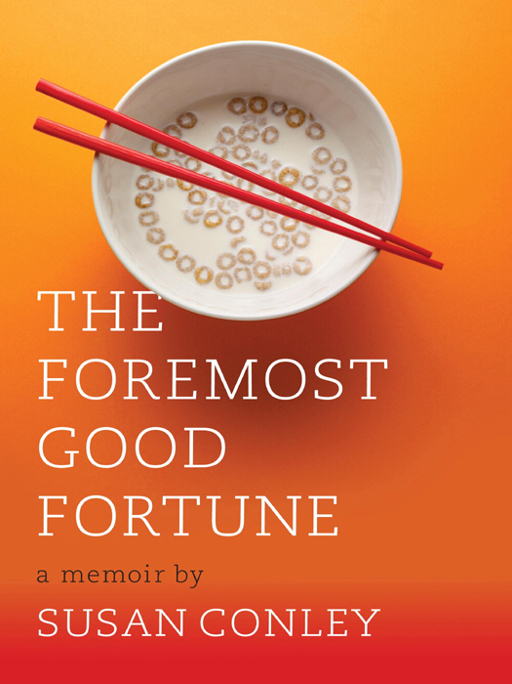

Jacket photograph by Stephen Lewis

Jacket design by Barbara de Wilde

v3.1

To Tony

and to Aidan and Thorne

DHAMMAPADA 15

Hunger: the foremost illness.

Fabrications: the foremost pain.

For one knowing this truth

As it actually is,

Unbinding

Is the foremost ease.

Freedom from illness: the foremost good fortune.

Contentment: the foremost wealth.

Trust: the foremost kinship.

Unbinding: the foremost ease.

—translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Contents

I - Hall of Celestial and Terrestrial Union

You Should Have Come Earlier

The Jingkelong

The Great Wall Is Older Than Johnny Cash

Building a Chinese Boat

I Don’t Speak Chinese

Xiao Wang

Chabuduo

“How to Handle the Stress of an International Move”

Mongolian Hot Pot

Piaoliang

The Bag Lady

How Long Have You Lived Here?

II - Hall of Mental Cultivation

Houhai Lake

Human Migration

Stuffed Like Mao

The Three T’s and the One F

I Love You. End of Discussion.

Tell Me in Centimeters

Inner Mongolia

The Cruelest Month

IV - Palace of Tranquil Longevity

Clouds or Butterflies

Decade by Decade

Chinese Blessing

You Are Here

Spaceship

V - Palace of Earthly Tranquility

How to Hire an Ayi

Science Experiment

No Assembling

Ecological Farm

Starter Buddha

Beijingren

Yashow Market

Breast Behavior

Homework

Foreign Intelligence

The United Nations of Second Graders

VI - Hall of Preserving Harmony

Homing Pigeon

Israel

Top Gun

Office Party

Rose

Glitter

Chinese Basketball

Caskets

Tiger Leaping Gorge

Houmen: The Back Gate

Qianmen:

The Front Gate

It’s late on a cold April night in Portland, Maine, and I lie on the couch staring hard at a glossy pullout map of Beijing. My two boys are asleep upstairs in their beds, and my husband has just landed in China to buy swivel chairs for his new office there. I want this map to offer a clue of what a life in Beijing would look like. But the more I gaze at street names, the more distant they feel: would we live on a road called Yongdingmen Xibinhe? Or Changchunqiao?

Tony calls me from the crowded lobby of the Grand Hyatt Beijing. He says the capital city is reinventing itself. There’s so much construction, whole streets he once lived on are gone. I pull the map closer and trace one long Chinese highway with my finger while he talks. The black line winds around the city center like a snake. “I can’t get a feel,” I say out loud and try to laugh into the phone, but the laughter sounds forced. “I’m staring at the Forbidden City. It’s smack in the middle of everything, isn’t it?”

There’s a slight delay on the line—a second of silence that neither of us fills. “It’s a city within a city,” Tony says. “With shrimp dumplings so good they may change your life.” I close my eyes and listen to his voice. I’ve been hearing China stories from my husband as long as I’ve known him.

In the eighties he hitchhiked in China for a year on a college grant and became so curious he stopped out for another stay. When I married Tony, I felt China’s tidal pull. In San Francisco I pretended to be invested in a legal career, while Tony taught photography at a Chinese community center—walking old men and women around Chinatown, cameras dangling from their necks, and then back to the darkroom he’d built.

We drove to San Diego, where Tony wrote grad papers on Sino-American trade treaties, and I got a master’s in poetry. When we migrated to Boston, I taught at a downtown college and Tony put on a consulting tie. But the closest he got to Beijing during the Boston years was our favorite dumpling house. Then we moved to Maine—as far east as we could go in the continental United States. China sat in the rooms of our house like a question.

I can hear Tony say something fast in Mandarin to someone in the hotel lobby. He has what people in China call “pure tones.” That means he speaks Chinese almost as if he’s lived there all his life. And I don’t mean to imply that my husband didn’t study his brains out to get a handle on a quadrant of Mandarin’s fifty-five thousand characters. But he’s good at it in an uncanny way. It’s the main reason, really, why I’m still awake at close to midnight, pulling a green wool blanket over my legs, trying to decide if I can transplant my kids to a country where they don’t have one friend.

It’s time I gave Tony some kind of sign. I’ve been stalling. There’s an apartment lease in Beijing waiting for initials and a work contract that needs negotiating. The question is about geography. But it runs deeper. Given the choice, our two little boys would say they’re doing fine, thank you. They are four and six and believe life in Maine means clear oceans and no reason to tinker. No cause to climb on a jumbo jet and fly into the next hemisphere. Or to start over in a new school, in a new city, where they do not speak the language.

No one has to explain to me that the journey will be about confronting unknowns: the nuanced language, and a history so rich that Marco Polo and Genghis Khan both sharpened their teeth there. But also the unknown of the person I’ve most recently become—a mother still unsure of her new job description. A nap czar and food commandant. Who is

she

? That woman who keeps a pencil drawing of a thermometer taped to the fridge to remind her kids that her temper is rising?

“You haven’t asked,” is what I finally whisper into the phone.

Tony is confused now. “Asked what?”

“You have to ask me to come to China.” I speak louder. “I need you to ask.” Then I smile to myself because I am a person guided by words and he is not. But when he starts to talk, I can’t detect even a trace of impatience, and that’s how I know my answer.

“Okay,” he says slowly, and there’s a lilt to his voice. “I’m asking if the four of us can move to China.” I hear him take an excited breath. “I’m formally asking if you’ll come.”

That’s when I hear myself say yes. Yes to the cultural zeitgeist that living in China the year before the Olympics will surely be. Yes to an exit from the grind of Tony’s commuter-flight life. Yes to all the unknowns that will now rain down. Because that one small word sets our family in motion. A month later I resign from the creative writing lab I’ve been running. We rent out our Portland house and truck old high chairs and baby strollers and frying pans to a storage facility with a corrugated metal roof. Then we ship boxes of rain boots and soccer balls and Early Readers on an airplane to Beijing.

What unfolds in China is the bounty we hoped for: the universe is much bigger once you leave New England. We are meant to grow as a family in that way you hear Americans do when they head east, to become bigger risk takers and deepen our connections to one another. And we do. We eat

jiaozi

and

baozi

and brown, pickled tea eggs. We drive the crooked

hutong

alleys with screaming taxi drivers and climb remote mountains on ancient horses. What’s more, the boys and I learn how to speak beginner Mandarin, while Tony dusts off a few vocabulary words.

But what happens while we’re there is that one of us gets cancer. It turns out to be me. This is my excuse for why I haven’t held on to more Mandarin grammar. For us, cancer becomes the story within the China story. China and cancer are both big countries, so there’s a lot to say about each. But let me start back at the beginning. It’s Monday in Beijing, and I have to go pick up the boys from their first day of school.

I

Hall of

Celestial and

Terrestrial

Union

You Should Have Come Earlier

Here’s the setup: I’m in the passenger seat of a blue Buick minivan driving through downtown Beijing at three o’clock on a blistering afternoon. A fifty-three-year-old Beijing local named Lao Wu is driving. He will always be the one driving in this story. He wears pressed high-waisted blue jeans and a sharp tan Windbreaker. Driving is his job; that is to say, he’s a full-time driver. When Lao Wu came back home from the fields after the Cultural Revolution, the high schools had been closed. That was the week he learned to drive a Mack truck, and he’s been driving ever since.

This is my third day in Beijing, and jet lag still pulls me down by my ankles. I lean back in the seat, my mind thick with sleep, and the van slows so I can count twenty waitresses lined up outside the Sichuan Xiao Chi dumpling house. The girls wear blue cotton

qipaos

and do jumping jacks on the sidewalk, then they salute a head waitress who stands on a small, black wooden box. Next they let out a cheer and march in a circle on the sidewalk. The head waitress calls out more instructions (How to fold the napkins? How to take a drink order?) and the girls yell back in a call and response. Then they salute their leader one more time and march into the restaurant.