The Friar and the Cipher (17 page)

Walsingham, who had never trusted Stafford (he had a Catholic wife), had spies watching him from the very beginning and soon learned of Stafford's treachery. But since Stafford wasn't especially subtle at espionage, Walsingham left him in place. Walsingham wanted to prove to Elizabeth that Mary was a traitor, so he set a trap.

He had one of his own agents, Thomas Philips, investigate Mary's household, and sent another agent, a captured Catholic spy named Gilbert Clifford, to the French embassy in London to offer himself as a courier for Mary. Mary and Clifford arranged to have enciphered letters smuggled out in waterproof packages inside the stoppers of the kegs of beer that were routinely delivered to the house to which Mary was confined. The arrangement was that Mary wrote the letters, her secretary transcribed them in ciphertext, the letters went out with the old beer, Clifford took them to the French embassy, the French embassy sent them to Stafford, and Stafford handed them over to the Spanish ambassador.

Unbeknownst to the conspirators, every letter Mary wrote or received went through Walsingham first. By this time Walsingham had an entire cipher department working out of his house in London, with Philips his chief cryptographer. Sometimes Walsingham just read Mary's letters and passed them along as written; sometimes he changed them slightly; and sometimes he kept them and sent his own versions instead.

It was through this unofficial channel that Walsingham learned that the Spanish were planning to build an armada and invade England. So dire was the threat that in 1587 he took the unheard-of step of writing out a covert plan of defense in order to impress upon Elizabeth the urgency of the situation so that she would appropriate funds for his networks. Entitled

Plot for Intelligence out of Spain

, the document outlined a number of surreptitious operations. One of these was to send an agent to Crakow, where Walsingham had a contact who claimed that he could steal the pope's personal correspondence and thereby intercept communications between Spain and the Vatican.

Walsingham's secret agent in Crakow was John Dee.

DEE HAD NEVER GOTTEN

the paid position at court that he wanted and was continually scrounging about for money, but he did whatever Elizabeth asked, no matter how trivial. When she had a toothache and refused to have it pulled, he personally went abroad to converse with the best dentists in Europe for alternate remedies. (Eventually, one of the queen's friends, Bishop Aylmer, had to have one of his own teeth pulled to persuade her to do the same.) Over the years, Walsingham had made use of Dee in various ways. He had dispatched him to France in 1571 to make a horoscope of the Duke d'Anjou, Elizabeth's French suitor (and come back with whatever information he could about French schemes to dethrone the queen). Whenever anybody made a little wax figure of Elizabeth and stuck pins in it, as people sometimes did, Dee was duly called on to mumble incantations and undo the spell. Walsingham sent English explorers and geographers like Richard Hakluyt to Dee for advice and the use of his library, consulted him personally about Admiral Drake's expedition, and encouraged him to find in his old books academic rationales for English territorial expansion. Dee obliged in 1577 by writing two books on the subject,

General and Rare Memorials

and

Brytanici Imperii Limites,

the latter of which included a map of all the lands to which his research supported Elizabethan claims. In so doing, he became the first scholar to formulate the idea of a British empire. “Nov. 28th, [1578], I spake with the Quene hora quinta; I spake with Mr. Secretary Walsingham. I declared to the Quene her title to Greenland, Estetiland and Friseland,” Dee recorded in his diary.

In June 1583, Dee had had a visitor, Lord Albert Laski, a Polish prince on an unofficial tour of England. Laski was a Catholic, but as an immense landholder and powerful nobleman he represented an entrée into the court of Rudolph II, king of Bohemia and Hungary. More than that, Laski was ambitious, and ambitious men were useful to Walsingham. Accordingly, the English government went to considerable trouble to make him feel at home. Laski, who was preoccupied with the study of alchemy (land and serfs were all very well, but gold was liquid) and considered himself something of a patron of scientists, expressed an interest in meeting the great English alchemist John Dee, of whose work he had heard so much. Dee noted the meeting in his diary:

June 15th [1583], abowt 5 of the clok cam the Polonian Prince Lord Albert Lasky down from Bissham, where he had lodged the night before, being returned from Oxford whither he had gon of purpose to see the universityes, where he was very honorably used and enterteyned. He had in his company Lord Russell, Sir Philip Sidney, and other gentlemen: he was rowed by the Quene's men, he had the barge covered with the Quene's cloth, the Quene's trumpeters, &c. He cam of purpose to do me honor, for which God be praysed!

Unfortunately, by the time of Laski's visit, John Dee's notion of science and mathematics had descended into the grotesque. A year earlier, he'd made the acquaintance of, and subsequently hired, a man who would exert enormous influence over him for the rest of his life, Edward Kelley.

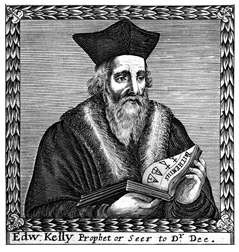

Kelley had materialized out of the shadows of the Elizabethan underworld one evening to have his horoscope read, and stayed on with Dee, more or less, for the next six turbulent years. On the run from the law on a charge of counterfeiting, he was operating under the assumed name of Talbot when he arrived on the astrologer's doorstep. He had already had his ears lopped off as punishment for his crime and wore a black skullcap over his long, unkempt hair to hide the disfigurement. This gave him a macabre, slightly sinister look that recommended him to Dee, who was by this time engaged in surreptitious acts of magic and was looking around for someone to perform a particularly delicate supernatural task for him. Dee was looking for what the sixteenth century called a “skryer.”

A skryer was a spiritual medium, someone who, under the right circumstances, could establish a link between the terrestrial world and that of God and heaven. (There were some skryers who could summon up demons, of course, but Dee, a devoutly religious man, would have nothing to do with them.) In the course of his many foreign travels, Dee had purchased a crystal ball, which he called a magic mirror or “shew-stone.” It was one of his most prized possessions; he had showed it off to Elizabeth once when she came to visit. But, try as he might, when Dee peered into his rock he saw nothing. Consequently, he was on the lookout for someone to act as intermediary between himself and the angelic spirits. “[I] confessed myself a long time to have been desirous to have help in my philosophical studies through the company and information of the blessed angels of God,” Dee wrote. When he mentioned the problem to Kelley, the younger man offered to give it a try. “[Kelley was] willing and desirous to see or show something in spiritual practice.”

Edward Kelley,

BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

Kelley was even better at skrying than Dee could have hoped. Kelley saw all kinds of angels in the glass. He saw the angel Uriel, whom God had used to warn Noah of the impending flood. Uriel was a spirit Dee was particularly interested in meeting. He wasn't even an ordinary angel—he was an archangel. After Uriel, Kelley saw Michael, an even more prestigious archangel than Uriel, another on Dee's most wanted list. In fact, through Kelley, Dee got a chance to meet all the really important angels, the ones who could help him in his research.

But Kelley didn't just

see

the angels. He

talked

for them, or they talked through him. They used different voices and different forms. Sometimes they were male and threatening. Sometimes they were flirtatious women. Sometimes they were innocent little girls. Dee would ask them questions and Kelley would answer, roaming around the room, talking in curious, archaic languages, offering advice and revealing secrets, taking on various personalities.

So convinced was Dee that he was indeed in communication with the spirit world that he went to great lengths to ensure that his sessions with Kelley and the angels were productive. He had a whole procedure for it: for three days before, neither man could engage in “Coitus & Gluttony . . . [each must] wash hands, face, cut nails, shave the beard, wash all . . . [prayers should be said] 5 times to the East, as many to the West, so many to the South & to the North.” He wrote down every word of these sessions, and they are preserved in his diaries. “It is hard to find in print a more amazing farrago of nonsense,” the historian Henry Carrington Bolton noted in his book

The Follies of Science at the Court of Rudolph II

.

By the time of Lord Albert Laski's visit, Kelley was a valued member of Dee's household. But the séances at Mortlake had attracted others' attention as well. Word had got out to the countryside, and Dee was rumored to be a wizard and had become the subject of petty harassments. More important, knowledge of Dee and Kelley's activities had come to Walsingham's attention. A resourceful young scoundrel like Kelley was even more useful to an intelligence network than a credulous old man like Dee. Walsingham blackmailed Kelley into becoming a spy. So it was that when Lord Albert Laski went back to Crakow, he took Dee and Kelley and their wives and children with him.

It is difficult to evaluate their performance as secret agents. Inconspicuous they weren't.

They settled on Laski's estates and proceeded to spend his lordship's money on alchemical experiments at an alarming rate. Laski soon tired of them and sent them off to Prague to the court of Rudolph II with letters of introduction. Rudolph, whose childhood had been spent at the fanatically Catholic court of his uncle, Philip II of Spain, and who had been unbalanced by the experience, was known to have an interest in art and the occult. Alchemy and the search for the philosopher's stone dominated his life. He kept a fully equipped laboratory manned with alchemists and had once singed his beard while trying to turn lead into gold.

Rudolph II of Bohemia

Rudolph had a magnificently idiosyncratic collection of paintings, part masterpiece, part junk, which were hung helter-skelter on the walls of the palace, as well as a library of mystical manuscripts. He kept a menagerie of wild animals, which included a lion cub named Otakar. He maintained huge gardens filled with exotic plants, including flowers brought back from the New World. Rudolph grew the first tulip in Bohemia—he named it Maria, after his mother—and employed many botanists. Although he never married, he fathered many children, and a parade of women went in and out of the castle.

Rudolph, with the treasury of the empire behind him, was known to pay generously for his pleasures. Accordingly, in addition to legitimate scientists and artists—Rudolph supported the astronomer Tycho Brahe and bought paintings by Titian and Holbein—the emperor also attracted a hodgepodge of con men, forgers, and unscrupulous dealers in “curiosities.”

Kelley, especially, was in his element. While Dee obtained an audience with the emperor and lectured him on science and mathematics, introducing him to the work of Roger Bacon, Kelley turned lead into gold with the aid of a crucible equipped with a false wax bottom laced with gold filings. Emboldened by success, Kelley staged an even larger demonstration. He invited all of Rudolph's alchemists to witness one of his experiments and had a big box full of instruments and chemicals wheeled into the laboratory. He threw some iron and some red dust, “the philosopher's stone,” into the fire and then made everyone leave for an hour while he murmured mystical incantations. When the other scientists had cleared the room, Kelley's brother got out of the false bottom of the box and threw real gold nuggets into the fire.

Kelley's fame thus expanded at the expense of Dee's, and the old man became even more dependent on his protégé. Kelley used his power mercilessly. He would refuse to look into the crystal for Dee, which drove the aging philosopher to despair. Dee tried to get his ten-year-old son, Arthur, to skry for him, but no matter how long the boy sat and stared he never saw anything. When Kelley did condescend to hold a séance, the angels made strange requests. The climax to this absurd drama came when the angels demanded that Dee and Kelley share wives. (Jane, Dee's third wife, was much younger than he was and attractive. By contrast, Mrs. Kelley had long since ceased to interest Mr. Kelley.) Although he demurred at first—there was not much precedent for wife swapping in the Bible—the angels eventually convinced Dee that the command came from God, and he acquiesced.