The Fry Chronicles (21 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

My cynicism and self-criticism may seem distorted and overstated, but I do not think I exaggerate so very much. Certainly the distinction between Barry Taylor’s diligent integrity and my own indolent technique remains symbolic of something that is wrong in education and testing. Having said which, Cambridge was not so foolish as entirely to fail to recognize Barry’s qualities, and he did subsequently have a career in academia despite not getting the First-Class degree that a better system of examination would undoubtedly have awarded him. On the other hand, if continuous assessment existed in my day, and had there been a greater emphasis on written work and research and less on scrambling to produce essays against the clock in the examination hall, I would have been booted out within months. Perhaps two

streams of testing are required: one for plausible bounders like me and another for authentic minds like Barry.

A second Edinburgh Fringe season approached. This time I was exclusively bound up with the Cambridge Mummers, the drama club for whom I had appeared in

Artaud at Rodez

the previous year. Despite their reputation for progressive programming and emphasis on the modern, radical and avant-garde, they asked if I might consider allowing

Latin!

to join their repertoire. Caroline Oulton had written a play about the Swiss kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely; a friend called Oscar Moore had written a piece whose title I forget but which had darkly funny things to say about Dunstable; Simon McBurney and Simon Cherry were preparing a one-man show in which McBurney would play Charles Bukowski. A children’s play was also being devised, and the main evening show would be a production of the rarely performed Middleton and Dekker comedy

The Roaring Girl

with Annabelle Arden in the title role, under the direction of Brigid Larmour. It was Annabelle and Brigid who had co-directed the production of

Travesties

in which I had first seen Emma Thompson. All these shows would be presented for two weeks in that same cramped but historic Riddle’s Court venue off the Royal Mile.

After the May Term finished and I had completed my usual summer stint at Cundall Manor we rehearsed for two weeks in Cambridge. I stayed in digs (Queens’ was earning money from renting itself out for a business conference)

near Magdalene with Ben Blackshaw and Mark McCrum, who had, with what grown-ups call ‘commendable enterprise’, started a business called ‘Picnic Punts’. Every morning they would get up, dress themselves in striped blazers, white flannel trousers and boaters and go down to a mooring just opposite Queens’, where they kept a single punt. A wooden plank with a white cloth would be placed athwart the vessel as a table, a wind-up gramophone, ice bucket and all the accoutrements required to serve a cream tea with strawberries and champagne would be stowed somewhere, and Mark would erect a handwritten sign on the Silver Street Bridge with illustrations (he was handy at drawing and calligraphy) advertising a punt-ride up or down the Cam in the company of genuine undergraduates.

Ben was pretty and fey and blond and Mark impish and darkly handsome. The dreamy sight of them in their Edwardian whites was guaranteed to appeal to American tourists, day-tripping matrons and visiting schoolmasters of a Uranian disposition. Sometimes, as I hurried across a bridge between rehearsals, I might hear a Gershwin tune echoing off the stonework of the Bridge of Sighs or the slowing down and rapid rewinding of a Benny Goodman foxtrot drifting across the meadow opposite King’s and I would smile as I saw Ben and Mark poling their way along the Backs, cheerfully making up outrageous and incredible stories about Byron or Darwin for the edification of their credulous and awestruck customers. At day’s end, I would come back from my rehearsals, and they would return from the river, muscles aching, tired from talking nonsense, their day’s takings wrapped in the tablecloth, which would be emptied on the kitchen table. Every last currency note and coin was scooped up and

taken to the grocer’s in Jesus Lane to be spent on meat and pasta for that evening and bottles of wine and tea things and champagne for the following day’s punting. I don’t think Mark and Ben turned a penny’s profit, but they got themselves fit, ate and drank well and inadvertently started a trend in ‘authentic student punts’ that is going to this day in the hands of much savvier and harder-nosed entrepreneurs. Not once did either of them suggest that I contribute to the nightly supper fund, despite the fact that I always ate and drank the food and wine that it bought. There was a carefree charm to the pair that made me feel heavy, bourgeois and over-earnest.

I had agreed to be in

The Roaring Girl

, as well as reprising my role as Dominic Clarke in

Latin!

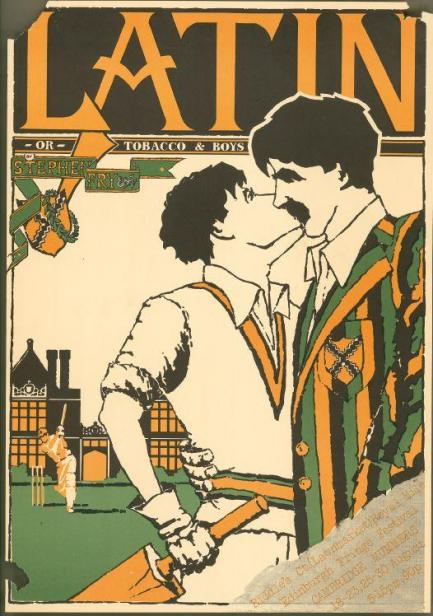

, with John Davies still in the part of Herbert Brookshaw. Simon Cherry would be directing once again and he had asked David Lewis, a History of Art student with whom he shared rooms in Queens’, to design a poster. The result was sensational. In the style of an Edwardian children’s storybook jacket Dave’s design depicted a school-uniformed boy and a young man in a teacher’s gown kissing, with a cricket game going on in the background. It was stunningly well done; the lettering, the colour palette, the whole look of it was exquisite. It shocked, but it was also funny, elegant and charming, which is what I hoped the play might be.

The Mummers’ producers, Jo and David, sent an army of volunteers (in other words the cast) around Edinburgh as soon as we arrived, to staple and paste up the posters for all our shows wherever we could. It soon became apparent that the

Latin!

poster was in great demand. The moment it went up it would be pinched, even if we took the common precautionary step of ripping it first

to decrease its collectability. I started to get messages left for me at Mummers’ headquarters in Riddle’s Court offering money for spares. It had become a collector’s item. In a rare burst of entrepreneurial PR zeal, I called up the

Scotsman

, pretending to be upset that our poster was being stolen as soon as it was put up. Sure enough, they obligingly ran a small paragraph with a picture of the poster, under the mini-headline: ‘Is this the most stolen poster in Edinburgh?’ The box-office went through the roof, and

Latin!

was sold out for the whole of the two weeks of its run.

Latin!

The most stolen poster of the 1980 Edinburgh Fringe.

Latin!

played in the mid-afternoon, but the main evening attraction was the

The Roaring Girl.

One of its cast members was a handsome and amusing Trinity Hall undergraduate called Tony Slattery, who had the look of a young Charles Boyer and the habits of an ill-trained but affectionate puppy. He read Modern and Medieval Languages, specializing in French and Spanish. He had represented Britain at judo, becoming national champion at his weight in his teens. He sang and played the guitar and was capable of being most dreadfully funny. Every night, in his role as some kind of foppish lord, he would put a larger and larger feather in his hat. By the time we came to the end of the first week it was brushing the ceiling. The entire cast, including Annabelle Arden, who had the lead role of Moll Cutpurse, fell into unrestrained giggles each time he executed a low bow which caused this enormous plume to bounce and waggle over our heads or into our faces. Sometimes when actors corpse it amuses the audience, but when it goes too far they often start to stir and mutter and hiss, which was what happened that evening. It was deeply unprofessional – but being deeply

unprofessional was one of the marvellous things about being students and being, well, not professional.

We all squeezed into digs somewhere in the New Town, hunkering down in sleeping bags on the floor, and even managed to make room for my sister Jo who came to visit and got on

very well

with certain members of the company. It was a wonderful time; the plays were all successful in their own way and we attracted good audiences. The pleasure was compounded by excellent reviews; the notoriously difficult Nicholas de Jongh was blush-makingly nice: ‘Stephen Fry is a name I shall look out for in the future, which is more than can be said for most of the writers and performers on the Fringe,’ he wrote. I have since been a sore disappointment to de Jong, I think, but at least we got off on the right foot. Even better news came when the

Scotsman

awarded us a Fringe First, the award that everyone aspired to win in those days.

Solemn but triumphant in the Mummers group photo celebrating our Fringe First Award.

A moment later, responding to Tony Slattery and revealing an unsurprising cigarette.

There was little time to see any other shows.

Electric Voodoo

, this year’s Footlights Revue, was composed of completely different performers from the year before. Hugh Laurie, that tall fellow with a flag of crimson on each cheek, wasn’t in it, nor were Emma or Simon McBurney. Emma did come to Riddle’s Court to see

Latin!

and she brought the Laurie chap with her.

‘Hullo,’ he said when she pushed him forward to meet me after the show.

‘Hullo,’ I said.

‘That was very good,’ he said. ‘I really enjoyed it.’

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘That is very kind.’

The triangles on his cheeks flamed redder than ever, and he popped off. I didn’t give him much more thought.

That night we had a party to celebrate the Fringe First. How tall and serious I look in the photograph.

In the late September of 1980 I arrived back in Cambridge for my final year. Although we could each have had a single set again, Kim and I decided that we wanted to carry on sharing and we were allocated A2 in the medieval tower of Old Court, the finest undergraduate rooms in college. Many graduates and dons had accommodation far less grand. The rooms boasted magnificent built-in bookshelves, a noble fireplace, an excellent gyp-room and bedrooms. The windows looked out on one side over Old Court and on the other on to the Master’s Lodge of St Catharine’s, the abode of the august Professor of Mathematics Sir Peter Swinnerton-Dyer, who was currently enjoying a period as Vice-Chancellor. The most prized item of furniture we added came in the form of a mahogany table that cleverly opened up into a wooden lectern. I had borrowed this from Trinity College as a prop for a lunchtime reading of the poems of Ernst Jandl and had somehow failed to return it. Kim added his Jaques chess set, Bang and Olufsen stereo, Sony Trinitron television and Cafetière coffee jug. We were far from the great age of designer labels, but brand names were beginning to acquire a new significance and desirability. I owned a pistachio-coloured Calvin Klein shirt whose loss I still mourn and a pair of olive-green Kickers of such surpassing splendour that I sob just to think of them.