The Fry Chronicles (25 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

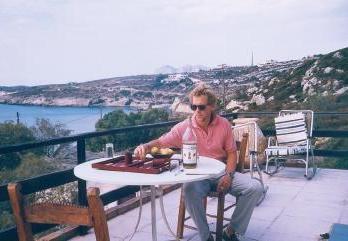

Hugh prepares to demolish me at backgammon. The retsina was satisfyingly disgusting.

In the clubroom I ran my first Smoker, furiously writing much of the material for it myself, terrified that the evening would run short. The Anthony Blunt Cambridge Spies

scandal was still being talked of at the time so amongst other pieces I wrote a sketch about a don, me, recruiting an undergraduate, Kim, for the secret service. I also wrote a series of quickies, mostly in the form of physical sight gags. Everything seemed to go magically well that night, and I was deliciously pleased and filled with a powerful new sense of confidence, as if I had discovered a whole new set of muscles I never knew I had.

A few days later I received a letter in the post from an assistant on the BBC’s successful new sketch show

Not the Nine O’Clock News

, which was in the process of making household names of Rowan Atkinson and his co-stars. One of the show’s producers, an ex-Footlighter called John Lloyd, had been in the audience of my Smoker and seen a quickie which he thought would work well on

Not

. Could they buy it?

In a fever of excitement I typed it out:

A man finishes a pee in a urinal. He goes to the sink, washes himself and looks for a towel. There isn’t one. He looks for anything he might dry his hands on. Nothing. He sees a man standing by the wall. He approaches him and knees him in the groin. The man doubles up with a huge exhalation of pain in the hot blast of which our hero happily dries his hands.

Yes, I know. On paper it is pretty lame, but it had worked OK that evening in front of the Smoker audience and it worked OK when Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones performed it on

Not the Nine O’Clock News

a month or so later. Over the years it was repeated many times and included in various Best Of compilations. I got used to receiving, right up to the end of the decade, cheques from

the BBC for randomly absurd sums. ‘Pay Stephen Fry the sum of £1.07’ and so on. The lowest was 14 pence, for sales to Romania and Bulgaria.

Just after I had sent off that written version of the quickie Hugh arrived in A2 for his usual chess, chat and coffee. I proudly told him the news that I was now a television writer. His face fell.

‘Well, that means

we

can’t do it now,’ he said, his eyes supplying the phrase that his mouth was too polite to add: ‘You daft tit.’

‘Oh. Oh I hadn’t thought of that. Of course. Damn. Bother. Arse.’

I had been so excited about selling material to television that it had never occurred to me that it meant we would now not be able to use it ourselves. Not thinking is one of the things I’m best at. All the same, when I saw my name included in the end credits of the episode in which my quickie appeared I did feel huggingly happy.

When the time came for the Late Night

Memoirs of a Fox

to go on at the ADC, Emma, Kim, Paul, Hugh and I were in the show and Hugh added to the cast a tall, blonde, slender and extraordinarily talented girl called Tilda Swinton. She was not a part of Cambridge’s comedy world, such as it was, but she was a magnificent actress, and her poise and presence made her the perfect judge in an American-courtroom sketch that Hugh had devised with some very slight assistance from me.

It is rather perfect to think of the pair of them playing American characters as students on the stage of the ADC. We would have called you mad if you had suggested that one day Hugh would go on to win Golden Globes for playing an American in a television

series and that Tilda would win an Oscar for playing an American in a feature film.

The previous term Jo Wade, who was Secretary of the Mummers, had drawn my attention to the fact that the Lent term would see the fiftieth anniversary of the club, which had been founded in 1931 by a young Alistair Cooke.

‘We should have a party,’ said Jo. ‘And we should invite him.’

Alistair Cooke was known for his thirteen-part documentary and book,

A Personal History of the United States

, and his long-running and greatly loved radio series,

Letter From America

. We wrote to him care of the BBC, New York City, USA, wondering if he had any plans to be in Britain in the next few months and if so whether he might be amenable to being persuaded to be our guest of honour at a dinner for the semi-centennial celebrations of the drama club he may remember founding. A drama club, we added, that was stronger and healthier than ever, having picked up more Fringe Firsts in Edinburgh than any other university drama society in the land.

He wrote back with the news that he had no plans to be in Britain. ‘However, plans can be changed. Your letter has so delighted me that I shall fly myself over to be with you.’

In the dining hall of Trinity Hall he sat between me and Jo and talked wonderfully of his time at Jesus College in the late twenties and early thirties. He spoke of Jacob Bronowski, who had the rooms above him: ‘He invited me to a game of chess and as we sat down asked me, “Do

you play classical chess or hypermodern?”’ He spoke of his friendship with Michael Redgrave, who succeeded Cooke as editor of

Granta

, Cambridge’s most intelligent student publication. As he spoke, he noted down a few words on his napkin. When it was time to propose the toast to Mummers and its next fifty years, he rose to his feet and, on the basis of those three or four scribbled words, delivered a thirty-five-minute speech in perfect

Letter From America

style.

Michael Redgrave and I were most annoyed that women were not allowed to act in plays in Cambridge. We were tired of those pretty Etonians from King’s playing Ophelia. We thought the time had come to change all that. I went to the Mistresses of Girton and Newnham and proposed the formation of a serious new drama club in which women might be allowed to take on women’s roles. The Mistress of Girton was P. G. Wodehouse’s aunt, or cousin or something, I seem to remember, and she was terrifying but kind. Once she and the Newnham Mistress had satisfied themselves that our motives were pure, aesthetic and honourable, which of course they only partly were, they consented to allow their undergraduates to appear in drama, and that is how the Mummers came about. Once the word got out that there was a new club which allowed women to act, hundreds of male undergraduates besieged me, begging to be cast in our first production. I remember holding auditions. One undergraduate from Peterhouse came to see me and recited a speech from

Julius Caesar

. ‘Tell me,’ I said to him as kindly as I could, ‘what subject are you reading?’ ‘Architecture,’ he replied. ‘Well, you carry on with that,’ I said, ‘I’m

sure you’ll be an excellent architect.’ He did indeed get a First in Architecture, but whenever I see James Mason now he says to me, ‘Damn. I should have taken your advice and stayed with architecture.’

The fluency, charm and ease with which Cooke spoke held the entire hall completely spellbound. He was one of those people who seemed to have been born to bear witness. Famously he had been in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles in 1968, only yards from Robert F. Kennedy when he was shot down and killed. He told us a story of another brush with political destiny that had taken place during the long vac that followed his setting up of the Mummers.

I went with a friend on a walking tour of Germany. It was the kind of thing one did then. Books strapped up in an arrangement of leather belts and slung over the shoulder as one tramped the meadows of Franconia, stopping off at taverns and guesthouses. We arrived in a small Bavarian valley late one morning and found a perfect beer garden, overlooked by a pretty old inn which tumbled with geraniums and lobelias. As we sat sipping our Steins of lager, chairs were being arranged in rows in the garden. It seemed that some sort of concert was in the offing. By and by two ambulances drew up. The drivers and stretcher-bearers got out, yawned, lit cigarettes and stood by the open tailgates of their vehicles as if it were the most normal thing in the world. People began to arrive, and soon every chair in the beer garden was taken and the dozens who couldn’t get a seat stood at the back or sat cross-legged on the grass in front of the small temporary stage. We

simply could not imagine what was going to happen. An enthusiastic crowd, but no musicians and, most strangely of all, those ambulance drivers and stretcher-bearers. At last a pair of huge open-topped Mercedes tourers arrived, crammed like a Keystone Kop car with more uniformed figures than they could comfortably hold. They all leapt out, and one of them, a short man in a long leather coat, marched to the stage and began to speak. Not speaking German at all well, I could not understand much of what he said, but I could make out the repeated phrase “

Fünf Minuten bis Mitternacht! Fünf Minuten bis Mitternacht!

Five minutes to midnight! Five minutes to midnight!” It was all most strange. Before long, women in the crowd would swoon and faint, and the stretcher-bearers would start forward to collect them. What kind of speaker was it who could be so

guaranteed

to cause people to faint with his words that ambulances came along beforehand? When the man had finished speaking he strode up the aisle, and his elbow barged against my shoulder as I leant out to see him go, and he backed into me, turned away as he was to take the ovation of the crowd. He immediately grabbed my shoulder to stop me from falling, ‘

Entschuldigen Sie, mein Herr!

’ he said. ‘Excuse me, sir!’ For some years afterwards, whenever he came on in the cinema newsreels as his fame spread, I would say to the girl next to me. ‘Hitler once apologized to me and called me sir.’

When the evening was over Alistair Cooke shook my hand goodbye and held it firmly, saying, ‘This hand you are shaking once shook the hand of Bertrand Russell.’

‘Wow!’ I said, duly impressed.

‘No, no,’ said Cooke. ‘It goes further than that. Bertrand Russell knew Robert Browning. Bertrand Russell’s aunt danced with Napoleon. That’s how close we all are to history. Just a few handshakes away. Never forget that.’

As he left he tucked an envelope in my pocket. It was a cheque for £2,000 made out to the Cambridge Mummers. On a compliment slip with it he had written, ‘A small proportion to be spent on production, the rest for wine and senseless riot.’

One morning in February Hugh came into A2, waving a letter.

‘You were in that film they made here, weren’t you?’ he said to me and Kim.

‘

Chariots of Fire

, you mean?’

‘Well they’ve got some sort of premiere at the end of March and a party at the Dorchester Hotel and they want the Footlights to be the entertainment. What do you think?’

‘It would make sense if we could actually see the film first. So we could do a sketch about it, or at least make some kind of reference?’

Hugh consulted the letter. ‘They’re suggesting we go to London on the morning of the thirtieth, go to the screening for film critics that’s taking place in the afternoon, rehearse in the hotel ballroom and then we’ll be put on after the dinner.’

The day before taking the train to London I called my mother to tell her what we were up to.

‘Oh, the Dorchester,’ she said. ‘I haven’t been to the Dorchester for years. In fact, I remember the last time clearly. Your father and I went to a ball and it broke up early because the news of John F. Kennedy’s assassination came through, and nobody felt like carrying on.’

On the appointed day the core Footlights team settled down in an empty cinema for the screening of the film, quite expecting to be depressed by a low-budget British embarrassment. As we came out, I brushed a tear from my cheek and said, ‘Either I’m in a really odd mood or that was rather fantastic.’

Everybody else seemed to be in agreement.

We hastily put together an opening sketch in which we ran on to the stage in slow motion. Steve Edis, whose ear was every bit as good as Hugh’s, had absorbed Vangelis’s distinctive musical theme and reproduced it on the piano.

After hanging about for hours in a small dining area set aside for toast masters in red mess jackets and what used to be called the upper servants, we were at last on.

‘My lords, ladies and gentlemen,’ said the MC into his microphone, ‘they twinkled in the twenties and now they’re entertaining in the eighties. It’s the Cambridge University Footlights!’

Our slo-mo running on stage to Steve’s lusty rendition of the film score went extremely well, and from the opening explosions of laughter and applause we settled confidently into our material. At some stage however it became apparent that we were losing the audience. There was rustling, murmuring, chair scraping and whispering. Dinner-jacketed men and evening-gowned women were scampering towards the back of the ballroom and … well, quite frankly … leaving.