The Fry Chronicles (46 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

Hugh, Katie and Nick Symons shared a house in Leighton Grove, Kentish Town; I had my Bloomsbury flat; Kim stayed on in Chelsea. We all saw each other as much as possible, but I was about to be busy performing eight times a week on the West End stage.

Richard Armitage had arranged with Patrick and the

Forty Years On

producers that in November I would be released from the run of the play for a few days, so that I could travel up to Leicester for the opening of

Me and My Girl

: this contractual clause was insisted upon not because Richard kindly believed I should have the treat of attending the first night of a musical to which I had contributed a script, but because he wanted to be sure that I would be on hand should the dress rehearsal and opening demonstrate a need for urgent, unforeseen rewrites.

We had participated in some strange conversations over the preceding months in which Richard had proved himself capable of changing hats mid-sentence, shuttling

between his identity as the show’s producer, the heir and manager of the composer’s estate and, not least so far as I was concerned, my agent. ‘I have had a word with myself,’ he would say, ‘and I have agreed to my outrageous demands as to your financial participation in this project. I wanted to cut you out of any backend, but I absolutely insisted, so much to my annoyance you have points in the show, which pleases me greatly.’

Early on in the rehearsal process Leslie Ash had not responded well to her dance and vocal lessons and by mutual agreement she had dropped out of the cast. I sat in Richard’s office one afternoon as he rubbed his chin anxiously. Who on earth could we cast as Sally?

‘What about Emma?’ I said. ‘She sings wonderfully and, while she may not have done any tap dancing, she’s surely the kind of person who can do anything she turns her mind to.’

Richard’s personality once more split before my eyes. ‘Of course. Brilliant. I want her,’ he said, before riposting, ‘Well, if you do, you’ll damned well have to pay through the nose for her. Oh now, come on, be reasonable. She has no experience, no real name. That’s as maybe, she is one of the greatest talents of her generation and, as such, she’ll cost you.’

I left Richard to wrestle the matter. I understood that he fell short of actually beating himself up and managed before too long to end his tense negotiations by shaking his hand on a deal satisfactory to both of him.

Emma duly joined the cast. She knew Robert Lindsay well, having worked at the Royal Exchange in Manchester, where Robert had presented his excellently received Hamlet. In fact I believe I am right in saying that Emma

and Robert had known each other

very

well back then. Really jolly well indeed. Oh yes.

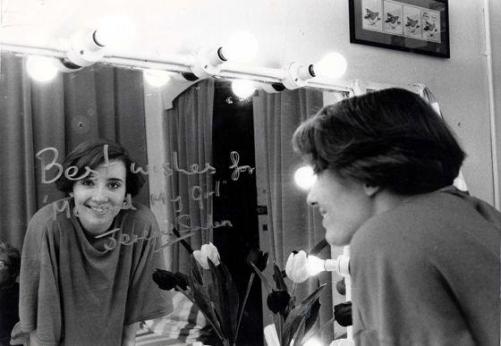

Me and My Girl.

Emma’s dressing-room on the first night.

Forty Years On

had to undergo one or two cast changes for its West End run. John Fortune and Annette Crosbie were unavailable for the transfer, and their roles went to David Horovitch and Emma’s mother, Phyllida Law. The boys were recast too: the local Chichester lads who had thrown themselves into their roles with such aplomb and good spirits were now replaced by London stage-school professionals, who were just as sparky and cheerful and a great deal more streetwise and experienced.

The day before the opening, during the interval between the technical run and the evening dress rehearsal, I walked out of the Queen’s Theatre stage door with David Horovitch and a group of these boys, heading for a pasta restaurant that they with their Soho savvy had recommended. Alan Bennett was out in the street, attaching bicycle clips to his trousers.

‘Are you going to join us for spaghetti?’ I asked him.

‘Yes, do!’ said the boys.

‘Oh no,’ said Alan, in slightly shocked tones, as if we were inviting him to a naked orgy in an opium den. ‘I shall cycle home and have a poached egg.’ Alan Bennett is always excellent at being as much like Alan Bennett as you could reasonably hope. A keen mind, a powerful artistic sensibility, a fierce political and social conscience – but a man of bicycle clips and poached eggs. Is it any wonder that he is so loved?

My name was now up in neon on Shaftesbury Avenue. I was too embarrassed to take a picture, which now, of course, I regret. I do have a photograph of the first-night

party. I should imagine I was very happy. I had every reason to be.

Paul Eddington was happy too, enjoying a ripe and fruity time in his career. He had just been elected to the Garrick Club, which gave him enormous pleasure, and he and Nigel Hawthorne had been paid a large sum of money for a TV commercial, which pleased him almost as much.

‘A

very

large sum,’ he said happily. ‘It’s to advertise a new Cadbury’s chocolate bar called Wispa. Nigel whispers in my ear in his Sir Humphrey character – half a day’s work for the most extraordinary fee.’

‘Gosh,’ I said, ‘and do Tony Jay and Jonathan Lynn get a good wedge too?’

‘Ah!’ Paul winced slightly at my mention of the names of the writers and creators of

Yes, Minister

, a mention I had not made mischievously but out of genuine curiosity as to how these things worked. ‘Yes. Nigel and I had a twinge of guilt about that, so we’re sending them each a case of claret. Jolly good claret.’

There is a chasm between writers and performers: for each, life often looks better across the divide, and while I am sure Tony and Jonathan were pleased to receive their case of jolly good claret, I cannot doubt that they may have preferred the kind of remuneration Paul and Nigel were enjoying. As I was to discover, however, writing has its rewards too.

One night, as the curtain came down, Paul whispered in my ear with delighted triumph, ‘I can tell you now. It’s official. I’m Prime Minister.’

That night the final episode of

Yes, Minister

had been broadcast. It ended with Jim Hacker succeeding to the

leadership of his party and the country. Keeping the secret, Paul told me, had been the hardest job he had ever had.

I settled into the run of the play. There were six evening performances a week with matinees on Wednesdays and Saturdays. I would be saying the same lines to the same people, wearing the same clothes and handling the same props eight times a week for the next six months. Next door in the Globe Theatre (now called the Gielgud) a show set in a girls’ school called

Daisy Pulls it Off

was running, and the cast of schoolgirls and schoolboys in each got on

very well together

, as you might imagine. Each Wednesday afternoon in the interval between matinee and evening performance there would be a backstage school feast, the boys hosting in the Queen’s one week, the girls in the Globe the next. Further along the street stood the Lyric Theatre, where Leonard Rossiter was playing Truscott in a revival of Joe Orton’s

Loot.

One evening we were stunned to hear that he had collapsed and died of a heart attack just before going on. Only a few months earlier both Tommy Cooper and Eric Morecambe had also died on stage. A small selfish and shameful part of me regretted the certainty that I would now never meet or work with those three geniuses at least as much as I mourned their passing or felt for the desolation such sudden deaths must have brought their families.

November came, and it was time for me to go up to Leicester for the opening of

Me and My Girl.

The plan was to arrive on Thursday for the dress rehearsal, stay on Friday for the first night and be back in London in time for the Saturday matinee and evening shows of

Forty Years On

. Who meanwhile would be taking my place as Tempest? I was horrified to discover that it would be Alan Bennett himself,

reprising his original performance from 1968. Horrified, because I would, naturally, miss the chance to see him.

He came into the dressing-room I shared with David Horovitch on the Monday evening of that week.

‘Oh, Stephen, I’ve got a funny request. I don’t know if you’ll want to accede, but I’ll put it to you anyway.’

‘Yes?’

‘I know you aren’t going till Thursday, but would you mind if I went on as Tempest on the Wednesday matinee and evening as well?’

‘Oh goodness, not at all. Not

at all

.’ The dear fellow was obviously a little nervous and wanted to dip his toes in the water and feel his way back into the role with a smaller matinee audience. The wonderful part of it all was that I could now be in that audience and watch him. For two performances. It is not often that an actor gets to see a production he is in, and while many prefer not to watch someone else playing their own part, especially if it is a master like Bennett, I was too much the fan to care if the comparison cast me in the shade. Which I knew it would. After all, he wrote Tempest for himself and he was Alan, for heaven’s sake, Bennett.

I watched him both times and went round to the dressing-room.

‘Oh, Alan, you were astounding. Astounding.’

‘Ooh, do you think so, really?’

‘I’m so pleased you were on today, but you know,’ I said, ‘you absolutely didn’t need to ease yourself in with a matinee performance, you were perfect from the start.’

‘Oh, that isn’t why I asked if I could go on today.’

‘It isn’t?’

‘To be honest, no.’

‘Well, then why?’

‘Well, you know I’ve got this film?’

Indeed I did know. Alan had written the screenplay for a film called

A Private Function

, which starred Maggie Smith, Michael Palin and Denholm Elliott. I was planning to catch it over the weekend.

‘You see,’ he said, ‘it’s the Royal Command premiere this evening, and I wanted a solid excuse not to have to go …’

It is a very Bennetty kind of shyness that sees per-forming on stage in front of hundreds of strangers as less stressful than attending a party.

Leicester passed in a blur. The dress rehearsal of

Me and My Girl

seemed fine, but without an audience it was impossible to tell whether any of the slapstick and big comic routines would really work. Robert and Emma were wonderful together. Robert’s comedy business with his cloak, with his bowler hat, with cigarettes, cushions and any other props that came his way was masterly. I hadn’t seen physical comedy this good outside silent pictures.

Me and My Girl

. Robert Lindsay and Emma Thompson.

I went round the dressing-rooms with good-luck bottles of champagne, cards, bunches of roses and expressions of faith, hope and gratitude.

‘Well, we are waiting for the final director now …’ said Frank Thornton, adding in his most lugubrious manner the answer to my unspoken question, ‘… the audience!’

‘Ah!’ I nodded at this wise actorly thought.

In the end the final director jerked up their thumbs with a loud ‘

Lambeth Walk

’ ‘Oi!’. They stood and cheered at the end for what seemed like half an hour. It was a most wonderful triumph, and everybody hugged each other and sobbed with joy just as they do in the best Hollywood

backstage musicals. Mike Ockrent’s magical and comically detailed direction, Gillian Gregory’s choreography, Mike Walker’s arrangements and a chorus and cast that threw themselves body and soul into every second of the two hours’ running time ensured as happy an evening as I can remember in the theatre.

I would not want to be misunderstood. Musicals are still not quite my thing, and I am sure there are plenty of you who will wince at the thought of pearly kings and queens and larky high kicks accompanying a 1930s rum-ti-tum-ti score. Nonetheless I was pleased to be involved with something so alien to my usual tastes and which bubbled and bounced with such unaffected lightness of touch and warm silliness and unapologetic high spirits. We bucked the trend for self-regarding, high-toned, through-sung operatic melodramas. Not just bucked, buck-and-winged. I liked the fact that we were presenting an evening that paid homage to the origins of the word ‘musical’ as an adjective not a noun. From its beginnings the genre was Musical Comedy, and we had all hoped that there was still a demand for that kind of theatre. At the party I leant forward to a beaming Richard Armitage.