The Fry Chronicles (45 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

For the next four or five years I fed

Loose Ends

on an almost exclusive diet of Trefusis. Just occasionally I might appear in the guise of another character. Ned’s favourite alternative to the Professor was Rosina, Lady Madding, a kind of crazed old Diana Cooper figure. Her voice was a compound of Edith Evans and my prep-school elocution teacher:

I hope you don’t mind sitting in here, at my age you get rather fond of draughts. I know you young people feel the cold terribly, but I’m afraid I rather like it. That’s right. Yes, it

is

nice, isn’t it? Though I wouldn’t really call it a cushion, Pekinese is a more common name for them. No, well never mind, he was very old – just throw him on the fire would you?

In April 1984 I drove down to Sussex to start my summer of

Forty Years On

. I’ll run through the cast list.

Paul Eddington had been promoted to the part that he had watched John Geilgud play nearly sixteen years earlier, that of the headmaster. Eddington was, of course, a big star of television situation comedy, well known and

loved as Penelope Keith’s harassed husband in

The Good Life

and more recently as Jim Hacker, the hopeless and hapless Minister for Administrative Affairs in the immensely popular

Yes, Minister.

He had been very friendly during the rehearsals in London, but I couldn’t help being slightly in awe of him. I had never worked in daily proximity with someone quite so famous before.

John Fortune took the role of Franklin that Paul had played in the original production. John was one of the greats of Cambridge comedy with John Bird, Eleanor Bron and Timothy Birdsall back in the late fifties. He had created with Eleanor Bron the legendary (and wiped) series

Where Was Spring?

His partnership with John Bird was to achieve great prominence again in the late nineties and beyond with their wildly intelligent and prescient satirical contributions to

Bremner, Bird and Fortune

.

Annette Crosby played the school matron. She is now best known as Victor Meldrew’s wife in

One Foot in the Grave

, but I remembered her as a fiercely glamorous Queen Victoria in

Edward VII

and an almost impossibly perky and delicious Fairy Godmother in the

The Slipper and the Rose.

Doris Hare appeared as the old grandmother. She was seventy-nine and a magisterial trouper of the old school, much loved for her years of playing Reg Varney’s mother in

On the Buses

. A fine young actor called Stephen Rashbrook took the part of the head prefect, while the rest of the school were played by local West Sussex boys.

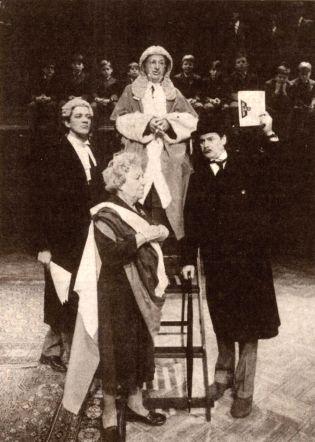

From

Forty Years On

, Chichester, 1984. Self, Doris Hare, Paul Eddington and John Fortune.

The Chichester Festival, begun in the sixties by Leslie Evershed-Martin and Laurence Olivier, presented each year a long summer of plays and musicals in a large, purpose-built, thrust-stage theatre. The 1984 season offered

The Merchant of Venice

,

The Way of the World

and

Oh, Kay!

as well as the

Forty Years On

that I had come down for. A tent, since replaced by a fully fledged second house called the Minerva, served as a space for smaller experimental productions. As a gig, as a booking, Chichester was much prized by old-school actors who liked the relaxed atmosphere of a prosperous south-coast town, a long season in repertory that didn’t make too many demands and the security of guaranteed festival attendance. This regular local audience was known collectively as Colonel and Mrs Chichester on account of their severe and hidebound tastes – Rattigan seemed to be the only post-war playwright they were able to stomach. Colonel and Mrs Chichester were not afraid to impart the exciting news that they went to the theatre to be

entertained

.

Patrick Garland was a delightful director, courteous, intelligent, benign and delicately tactful. In rehearsal, he had an endearing habit of addressing the perplexed boys in the cast as if they were members of an Oxbridge common room. ‘Forgive my mentioning it, gentlemen, but I do feel myself constrained to observe that the dilatory nature of the communal egress immediately consequent upon Paul’s second act exordium is injurious to the pace and dynamism of the scene. I should be so grateful if this deficiency were remedied. With grateful thanks.’

The play’s designer was Peter Rice, whose son Matthew soon became a lifelong friend. When not assisting his father he dug the garden of the little house he had hired for the season, shot rabbits and pigeons, skinned and plucked same and cooked them into exquisite suppers. He played the piano, sang songs, sketched and painted. His voice was not unlike Princess Margaret’s: high, grand and piercing. Perhaps he had spent too much time in her

presence, being a close friend of her son, David Linley, with whom he had been at Bedales.

Unlike Matthew, whose cottage was a charming rural retreat in the Earl of Bessborough’s estate, I had taken a rather dull modern flat a short walk from the Festival Theatre. I devoted my spare time to the script of

Me and My Girl

. Once or twice Mike Ockrent came down to work on it with me. Robert Lindsay had been duly cast as Bill, and the part of Sally was to be taken by Leslie Ash, subject to her taking lessons in tap and singing. The major character role of Sir John had been given to Frank Thornton, better known as the Grace Brothers floorwalker Captain Peacock in

Are You Being Served?

The show’s opening was all set for autumn in Leicester if I could just deliver a final rehearsal script within the next month.

My parents came down to Chichester from Norfolk for

Forty Years On

’s first night. I proudly introduced them to Alan Bennett and Paul Eddington. Alan in turn introduced us to his friends Alan Bates and Russell Harty.

‘I love a play where there are laughs and sobs,’ said Alan Bates, in a much camper voice than I would have imagined could ever issue from the lips of

The Go-Between

’s Ted Burgess and

Far From the Madding Crowd

’s Gabriel Oak, two of the manliest men in all of British film. ‘I mean, you’ve got to have a giggle and a gulp, haven’t you, or what’s the theatre for?’

Russell Harty, with anagrammatic

diablerie

, referred to Alan Bates as Anal Beast, or, in mixed company, Lana Beast.

First-night party for the

Forty Years On

‘transfer’, Queen’s Theatre, London, 1984. Katie Kelly (back to us, shiny bun), boys from the cast, self, Hugh Laurie, sister Jo.

I think I was disappointing as Tempest. In my mind I believed that I could play the part and play it with brilliance, but something held me back from being any better than competent. I was OK. Perfectly good.

Fine

.

That last is the worst word in theatre. When friends come backstage and use the word ‘fine’ about a play, a production or your performance you know they hated it. Often they preface it, out of nowhere, with the word ‘no’, which is fantastically revealing.

‘No, it was

fine

!’

‘No, really, I thought it was … you know …’

Why would they open a sentence with ‘No’ when they have not even been asked a question? There can be only one explanation. As they walk along the backstage corridors towards your dressing-room they have said inside their own head, ‘God, that stank. Stephen was embarrassingly awful. The whole thing was

ghastly.

’ Then they enter and, as if answering and contradicting themselves, they instantly say, ‘No, I thought it was great … no, really, I … mmm … I liked it.’ I know this is right because I so often catch myself doing exactly the same thing without meaning to. ‘No … really, it was fine.’

The production as a whole was considered a success, however. Colonel and Mrs Chichester enthused, and word soon got out that we were going to ‘transfer’.

‘Excellent news,’ Paul Eddington said to me one evening as we stood waiting to go on. I nearly wrote ‘as we stood in the wings’, but Chichester had an apron stage that thrust out into the auditorium on three sides, so we must have been standing behind the set.

‘Ooh!’ I said. ‘What good news?’

‘It’s official. We are going to transfer.’

‘Wow!’ I did a little dance. I had no idea what he was talking out.

It took me two days to work out the meaning of ‘transfer’. The boys in the cast seemed to know, the

women who served in the cafeteria knew, the tobacconist on the corner and the landlady of my flat knew, everyone knew except me.

‘Wonderful news about the transfer,’ said Doris Hare. ‘The Queen’s, I believe.’

‘Er …?’ Did a transfer mean a royal visit? Now I was even more puzzled.

‘I’ve played most of the houses on the Avenue, but this will be the first time I’ve played the Queen’s.’

The Avenue? I pictured us in some tree-lined boulevard giving an outdoor performance to a bored and affronted monarch. The idea seemed grotesque.

Later, Patrick said to me, ‘You will have heard the good news about the transfer?’

‘Indeed. Yup. Great, isn’t it?’

‘This will be your West End debut, I think?’

So

that

is what it meant! The production would be

transferred

from Chichester to the West End. A transfer. Of course. D’uh.

I finished the Chichester season in a frenzy. Mike Ockrent came to collect my final draft of

Me and My Girl

a week before we closed.

Back in London I decided, since Kim and Steve were so happy together at Draycott Place, that it was time for me to move out of Chelsea and set up on my own. For a hundred pounds a week I found myself the tenant of a furnished one-bedroom flat in Regent Square, Bloomsbury. Just me and the new love of my life.

Early in the year I had called Hugh up excitedly. ‘I’ve just bought a

Macintosh

. Cost me a thousand pounds.’

‘

What?

’

Hugh enjoyed about a week of relaying the news of my fantastic expenditure on something as absurd and unworthy of outlay as a raincoat before he discovered that this Macintosh was a new type of computer.

I was more insanely in love with this strangely beautiful piece of technology than anything I had ever owned before. It had a cable leading out of it that ended in a device called a ‘mouse’. The screen was

white

when you started it all up and loaded the system disk. The text that came up was black on white, like paper, instead of the fuzzily glowing green or orange on black offered by all other computers. An arrow on the screen could be activated by moving the mouse on the desk next to the computer. Images of a floppy disk and a dustbin appeared on screen and all along the top were words which, when clicked on with the mouse, pulled down a kind of graphical roller-blind on which menu options were written. You could double-click on pictures of documents and folders and windowpanes would open. I had never seen or imagined anything like it. Nor had anyone. Only Apple’s short-lived Lisa computer had used this way of doing things before and it had never had a place in the consumer or home market.

While it was being developed this graphical user interface had been referred to as WIMP, standing for Windows, Icons, Menus, Pointing-device. I was instantly a slave to its elegance, ease, usefulness and wit. Most of you reading this will be too young to imagine a time when

computers could have been presented in any other fashion, but this was new and revolutionary. Extraordinarily, it didn’t catch on for ages. For years and years after the January 1984 release of the Apple Macintosh the rivals – IBM, Microsoft, Apricot, DEC, Amstrad and others – all dismissed the mouse, the icon and the graphical desktop as ‘gimmicky’, ‘childish’ and ‘a passing fad’. Well, I shall refrain from going too deeply into the subject. I am fully aware of how minority a sport my love of all this dorky wizardry is. All you need know is that I, my 128 kilobyte Macintosh, Imagewriter bitmap printer and small collection of floppy disks were all very,

very

happy together. What possible need could I have for sex or human relationships when I had this?