The Fry Chronicles (26 page)

Read The Fry Chronicles Online

Authors: Stephen Fry

Surely we weren’t

that

bad? We had not only performed this in Cambridge but we had done evenings at the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith. I was prepared to believe that we might not be to everyone’s taste, but such a mass walk-out seemed like a studied insult. I caught Hugh’s eye, which held the wild, rolling look of a gazelle being pulled to earth by a leopard. I dare say my expression was much the same.

As we lumbered sweatily off stage, with Paul going forward for his monologue with the brave tread of an aristocrat approaching the guillotine, Emma whispered to us, ‘Someone’s shot Ronald Reagan!’

‘What?’

‘All the Twentieth Century Fox executives have left and gone to the phones …’

I rang my mother that night.

‘Well that’s settled then, darling,’ she said. ‘No member of this family ever goes to an event at the Dorchester again. It’s not fair on America.’

Back in Cambridge, Brigid Larmour was directing the Marlowe Society production that term,

Love’s Labour’s Lost.

This was the straight drama equivalent of the Footlights May Week Revue, a big-budget (by any standards) production mounted in the Arts Theatre, a splendid professional theatre with an alarming audience capacity of exactly 666. A combination of my persuasive rhetoric and Brigid’s natural charm succeeded in securing Hugh for his first Shakespearean role, that of the King of Navarre. I played the character with perhaps the best description in all of Shakespeare’s

dramatis

personae

: ‘Don Adriano de Armado, a fantastical Spaniard’. Only I wasn’t a fantastical Spaniard. For some reason, whenever I attempt Spanish it comes out as Russian or Italian, or a bastard hybrid of the two. I can manage a Mexican accent acceptably, so my Armado was an inexplicably fantastical Mexican. The major role of Berowne was played by a fine second-year actor called Paul Schlesinger, nephew of the great film director John Schlesinger.

The play opens with a long speech from the King in which he announces that he and the leading members of his court shall forswear the company of women for three years, dedicating themselves to art and scholarship. Hugh and Paul had one of those uncontrollable laughing problems. They only had to catch each other’s eye on stage and they would be unable to breathe or speak. For the first few rehearsals this was fine, but after a while I could see Brigid beginning to worry. By the time it came to the dress rehearsal it was apparent that Hugh would simply not be able to get out the words of the opening address unless either Paul was off stage, which made a nonsense of the plot, or some imaginative solution to the problem could be found. Threats and imprecations had proved useless.

‘I’m sorry,’ each said. ‘We’re trying not to laugh, it’s a chemical thing. Like an allergy.’

Brigid hit upon the happy notion of making

everyone

on stage in that scene, the King, Berowne, Dumain, Longaville and general court attendants, speak the opening lines together as a kind of chorus. Somehow this worked, and the giggling stopped.

At the first-night party I heard a senior academic and distinguished Shakespeare scholar congratulate Brigid on her idea of presenting the introductory speech as a kind

of communal oath. ‘A superb concept. It made the whole scene come alive. Really quite brilliant.’

‘Thank you, Professor,’ said Brigid without a blush, ‘it seemed right.’

She caught my eye and beamed.

The last term arrived. Another May Ball. Finals of the English tripos. The May Week Revue itself. Graduation. Farewell, Cambridge, hullo, world.

For the last Footlights Smoker before we began work on the show itself I recruited my old friend Tony Slattery, who fitted in with the greatest ease. He tore up the audience with guitar songs and extraordinary monologues of his own devising; one girl, according to the fatalistic janitor figure who looked after the premises, actually wet herself.

‘There’s such a thing,’ he said as he shook a canister of Vim over the damp cushion, ‘as

too

funny.’

I attempted to persuade Simon Beale to join us too, but he had enough singing and drama to fill his diary. I think he felt that comedy shows somehow weren’t quite him. With the addition of Penny Dwyer, with whom I had worked in Mummer productions and who could sing, dance, be funny and do just about anything, we had a cast to join me, Hugh, Emma and Paul Shearer for the big one, the May Week Revue that would go on to Oxford and then Edinburgh.

I wrote a monologue for myself based on Bram Stoker’s

Dracula

and a two-handed parody of

The Barretts of Wimpole Street

, in which Emma played Elizabeth, a bed-bound invalid, and I played Robert, her ardent suitor. Hugh

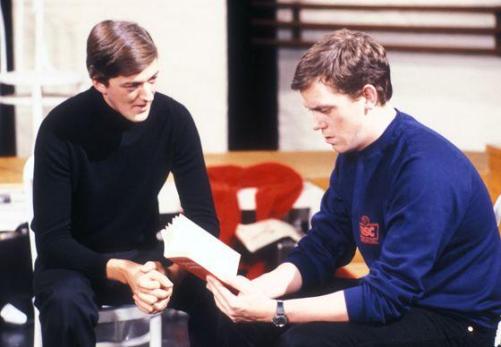

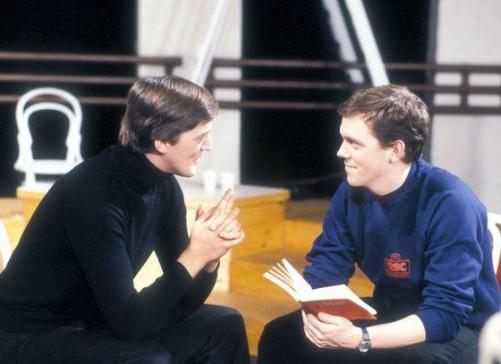

and I had both seen and found hilarious John Barton’s Shakespeare Masterclasses on television, in which he had painfully slowly taken Ian McKellen and David Suchet through the text of a single speech. We put together a sketch in which I did the same with Hugh. So detailed was the textual analysis that we never got further than the opening word, ‘Time’.

Hugh asked the previous year’s President, Jan Ravens, to direct us, and we began rehearsals in the clubroom. We put together a closing ensemble sketch, in which a ghastly kind of Alan Ayckbourn family playing after-dinner charades breaks down in animosity, revelation and disarray.

Performing the ‘Shakespeare Masterclass’ sketch with Hugh.

At some point we must have sat Finals and at another point I must have completed two dissertations, one on Byron’s

Don Juan

, another on aspects of E. M. Forster. I can remember neither, having knocked them both up in two frantic evenings: 15,000 words of drivel typed out at high speed.

When the news came that the English results were published I walked to the Senate House, against the walls of which huge notice-boards in wooden frames had been attached. I strained through the crowd of hysterical studentry and found my name in the Upper Second list. I had scored a dull, worthy and unexciting 2:1.

Peter Holland, a don from Trinity Hall who had supervised me for practical criticism and seventeenth-century literature, offered consolation.

‘They reread you for a First twice,’ he said. ‘You came very close. You got good Firsts in all your papers, top in Shakespeare again. But a 2:2 in the Forster dissertation and a Third in the Byron. That’s why they just couldn’t do it. Hard luck.’

The hurt was more to my pride than to my plans. To be honest, Cambridge was right, I had shown I could fly through written exams against the clock, but the serious work of a dissertation, which required the kind of originality, scholarship and diligence that I either didn’t possess or simply couldn’t be arsed to produce, exposed me for the plausible rogue that I was.

With Kim outside the Cambridge Senate House, celebrating our Tripos results. I was insanely in love with that Cerruti tie.

Hugh read Archaeology and Anthropology and got a far more amusing and likeable class of degree. He had been to one lecture, which gave him the material for a quite brilliant monologue about a Bantu hut, but otherwise had not disturbed his professors, written an essay or entered the faculty library. I think he would be the first to admit that you know more about Archaeology and Anthropology than he does.

The first night of our May Week Revue came. The show was called

The Cellar Tapes

, as much a reference to the underground Footlights clubroom in which it was born as to Bob Dylan’s

Basement Tapes

or any pun on Sellotape.

Hugh came on stage for the opening. ‘Ah, good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to the May Week Revue. We have an evening of entertainment, of – I got a Third by the way – sketch comedy, music and …’

We were under way. The Arts Theatre has one of the best auditoriums for comedy I know. Sitting in a spotlight with a leather book on my lap delivering the Dracula monologue, standing on stage with Hugh for the Shakespeare Masterclass, kneeling at the stricken Emma’s bedside, pouring tea for Paul Shearer in the MI5 recruitment sketch – all these moments were more pleasurable and thrilling in this theatre, on this occasion, before such an enthusiastic audience, than anything I had ever done before.

Hugh and I looked at each other after the curtain fell. We knew that, come what might, we had not disgraced the name of Footlights.

The Cellar Tapes

closing song. I fear we may have been guilty of embarrassing and sanctimonious ‘satire’ at this point. Hence the joyless expressions.

One night of the two-week run the word went round backstage that Rowan Atkinson had been spotted in the audience. I broke the habit of my (short) lifetime and peeped through at the house. There he was, there could be no mistake. Not the least distinctive set of features on the planet. We all performed with an extra intensity that may have made the show better or may, just as easily, have given it rather a hysterical edge – I for one was too excited to be able to tell. The great Rowan Atkinson watching us perform. Only a year and a half ago I had all but vomited with laughter at his show in Edinburgh. Since then

Not the Nine O’Clock News

had propelled him to major television stardom.

He came round backstage to shake our hands, a graceful and kindly act for a man so shy and private. My state of electrified enthralment stopped me from hearing a single word he said, although Hugh and the others told me afterwards that he had been charmingly complimentary about the evening.

Two nights later Emma’s agent, Richard Armitage, came.