The Gathering Storm: The Second World War (72 page)

Read The Gathering Storm: The Second World War Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Western, #Fiction

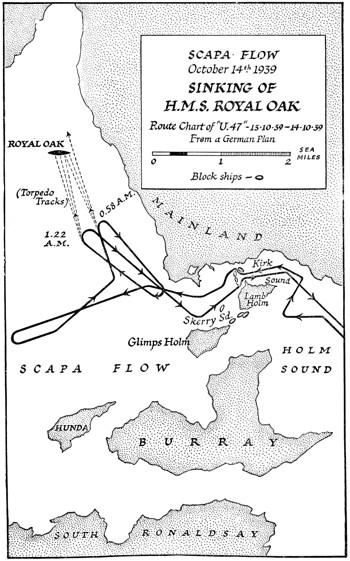

An account based on a German report written at the time may be recorded:

At 01.30 on October 14, 1939, H.M.S.

Royal Oak,

lying at anchor in Scapa Flow, was torpedoed by

U 47

(Lieutenant Prien). The operation had been carefully planned by Admiral Doenitz himself, the Flag Officer [submarines]. Prien left Kiel on October 8, a clear bright autumn day, and passed through Kiel Canal – course N.N.W., Scapa Flow. On October 13, at 4

A.M

., the boat was lying off the Orkneys. At 7

P.M

. – Surface; a fresh breeze blowing, nothing in sight; looming in the half darkness the line of the distant coast; long streamers of Northern Lights flashing blue wisps across the sky. Course West. The boat crept steadily closer to Holm Sound, the eastern approach to Scapa Flow. Unfortunate it was that these channels had not been completely blocked. A narrow passage lay open between two sunken ships. With great skill Prien steered through the swirling waters. The shore was close. A man on a bicycle could be seen going home along the coast road. Then suddenly the whole bay opened out. Kirk Sound was passed. They were in. There under the land to the north could be seen the great shadow of a battleship lying on the water, with the great mast rising above it like a piece of filigree on a black cloth. Near, nearer – all tubes clear – no alarm, no sound but the lap of the water, the low hiss of air pressure and the sharp click of a tube lever.

Los!

[Fire!] – five seconds – ten seconds – twenty seconds. Then came a shattering explosion, and a great pillar of water rose in the darkness. Prien waited some minutes to fire another salvo. Tubes ready. Fire. The torpedoes hit amidships, and there followed a series of crashing explosions. H.M.S.

Royal Oak

sank, with the loss of 786 officers and men, including Rear-Admiral H. E. C. Blagrove [Rear-Admiral Second Battle Squadron].

U 47

crept quietly away back through the gap. A blockship arrived twenty-four hours later.

This episode, which must be regarded as a feat of arms on the part of the German U-boat commander, gave a shock to public opinion. It might well have been politically fatal to any Minister who had been responsible for the pre-war precautions. Being a newcomer I was immune from such reproaches in these early months, and moreover, the Opposition did not attempt to make capital out of the misfortune. On the contrary, Mr. A. V. Alexander was restrained and sympathetic. I promised the strictest inquiry.

On this occasion the Prime Minister also gave the House an account of the German air raids which had been made on October 16 upon the Firth of Forth. This was the first attempt the Germans had made to strike by air at our Fleet. Twelve or more machines in flights of two or three at a time had bombed our cruisers lying in the Firth. Slight damage was done to the cruisers

Southampton

and

Edinburgh

and to the destroyer

Mohawk.

Twenty-five officers and sailors were killed or wounded; but four enemy bombers were brought down, three by our fighter squadrons and one by the anti-aircraft fire. It might well be that only half the bombers had got home safely. This was an effective deterrent.

The following morning, the seventeenth, Scapa Flow was raided, and the old

Iron Duke,

now a demilitarised and disarmoured hulk used as a depot ship, was injured by near misses. She settled on the bottom in shallow water and continued to do her work throughout the war. Another enemy aircraft was shot down in flames. The Fleet was happily absent from the harbour. These events showed how necessary it was to perfect the defences of Scapa against all forms of attack before allowing it to be used. It was nearly six months before we were able to enjoy its commanding advantages.

* * * * *

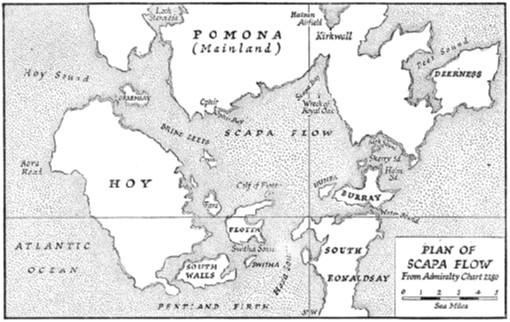

The attack on Scapa Flow and the loss of the

Royal Oak

provoked instant reactions in the Admiralty. On October 31, accompanied by the First Sea Lord, I went to Scapa to hold a second conference on these matters in Admiral Forbes’ flagship. The scale of defence for Scapa upon which we now agreed included reinforcement of the booms and additional blockships in the exposed eastern channels, as well as controlled minefields and other devices. These formidable deterrents would be reinforced by further patrol craft and guns sited to cover all approaches. Against air attack it was planned to mount eighty-eight heavy and forty light A.A. guns, together with numerous searchlights and increased barrage-balloon defences. Substantial fighter protection was organised both in the Orkneys and at Wick on the mainland. It was hoped that all these arrangements could be completed, or at least sufficiently advanced, to justify the return of the Fleet by March, 1940. Meanwhile, Scapa could be used as a destroyer-refuelling base; but other accommodation had to be found for the heavy ships.

Experts differed on the rival claims of the possible alternative bases. Admiralty opinion favoured the Clyde, but Admiral Forbes demurred on the ground that this would involve an extra day’s steaming each way to his main operational area. This in turn would require an increase in his destroyer forces and would necessitate the heavy ships working in two divisions. The other alternative was Rosyth, which had been our main base in the latter part of the previous war. It was more suitably placed geographically, but was more vulnerable to air attack. The decisions eventually reached at this conference were summed up in a minute which I prepared on my return to London.

1

* * * * *

On Friday, November 13, my relations with Mr. Chamberlain had so far ripened that he and Mrs. Chamberlain came to dine with us at Admiralty House, where we had a comfortable flat in the attics. We were a party of four. Although we had been colleagues under Mr. Baldwin for five years, my wife and I had never met the Chamberlains in such circumstances before. By happy chance I turned the conversation onto his life in the Bahamas, and I was delighted to find my guest expand in personal reminiscence to a degree I had not noticed before. He told us the whole story, of which I knew only the barest outline, of his six years’ struggle to grow sisal on a barren West Indian islet near Nassau. His father, the great “Joe,” was firmly convinced that here was an opportunity at once to develop an Empire industry and fortify the family fortunes. His father and Austen had summoned him in 1890 from Birmingham to Canada, where they had long examined the project. About forty miles from Nassau in the Caribbean Gulf there was a small desert island, almost uninhabited, where the soil was reported suitable for growing sisal. After careful reconnaissance by his two sons, Mr. Joseph Chamberlain had acquired a tract on the island of Andros and assigned the capital required to develop it. All that remained to grow was the sisal. Austen was dedicated to the House of Commons. The task, therefore, fell to Neville.

Not only in filial duty but with conviction and alacrity he obeyed, and the next six years of his life were spent in trying to grow sisal in this lonely spot, swept by hurricanes from time to time, living nearly naked, struggling with labour difficulties and every other kind of obstacle, and with the town of Nassau as the only gleam of civilisation. He had insisted, he told us, on three months’ leave in England each year. He built a small harbour and landing-stage and a short railroad or tramway. He used all the processes of fertilisation which were judged suitable to the soil, and generally led a completely primitive open-air existence. But no sisal! Or at any rate no sisal that would face the market. At the end of six years he was convinced that the plan could not succeed. He came home and faced his formidable parent, who was by no means contented with the result. I gathered that in the family the feeling was that though they loved him dearly they were sorry to have lost fifty thousand pounds.

I was fascinated by the way Mr. Chamberlain warmed as he talked, and by the tale itself, which was one of gallant endeavour. I thought to myself, “What a pity Hitler did not know when he met this sober English politician with his umbrella at Berchtesgaden, Godesberg, and Munich, that he was actually talking to a hard-bitten pioneer from the outer marches of the British Empire!” This was really the only intimate social conversation that I can remember with Neville Chamberlain amid all the business we did together over nearly twenty years.

During dinner the war went on and things happened. With the soup an officer came up from the War Room below to report that a U-boat had been sunk. With the sweet he came again and reported that a second U-boat had been sunk; and just before the ladies left the dining-room he came a third time reporting that a third U-boat had been sunk. Nothing like this had ever happened before in a single day, and it was more than a year before such a record was repeated. As the ladies left us, Mrs. Chamberlain, with a naïve and charming glance, said to me, “Did you arrange all this on purpose?” I assured her that if she would come again we would produce a similar result.

2

* * * * *

Our long, tenuous blockade-line north of the Orkneys, largely composed of armed merchant-cruisers with supporting warships at intervals, was of course always liable to a sudden attack by German capital ships, and particularly by their two fast and most powerful battle cruisers, the

Scharnhorst

and the

Gneisenau.

We could not prevent such a stroke being made. Our hope was to bring the intruders to decisive action.

Late in the afternoon of November 23, the armed merchant cruiser

Rawalpindi,

on patrol between Iceland and the Faroes, sighted an enemy warship which closed her rapidly. She believed the stranger to be the pocket battleship

Deutschland

and reported accordingly. Her commanding officer, Captain Kennedy, could have had no illusions about the outcome of such an encounter. His ship was but a converted passenger liner with a broadside of four old six-inch guns, and his presumed antagonist mounted six eleven-inch guns besides a powerful secondary armament. Nevertheless, he accepted the odds, determined to fight his ship to the last. The enemy opened fire at ten thousand yards and the

Rawalpindi

struck back. Such a onesided action could not last long, but the fight continued until, with all her guns out of action, the

Rawalpindi

was reduced to a blazing wreck. She sank some time after dark with the loss of her captain and two hundred and seventy of her gailant crew. Only thirty-eight survived, twenty-seven of whom were made prisoners by the Germans, the remaining eleven being picked up alive after thirty-six hours in icy water by another British ship.

In fact it was not the

Deutschland,

but the battle cruiser

Scharnhorst

which was engaged. This ship, together with the

Gneisenau,

had left Germany two days before to attack our Atlantic convoys, but having encountered and sunk the

Rawalpindi

and fearing the consequences of the exposure, they abandoned the rest of their mission and returned at once to Germany. The

Rawalpindi’s

heroic fight was not therefore in vain. The cruiser

Newcastle,

near-by on patrol, saw the gun-flashes, and responded to the

Rawalpindi’s

first report, arriving on the scene with the cruiser

Delhi

to find the burning ship still afloat. She pursued the enemy and at 6.15

P.M

. sighted two ships in gathering darkness and heavy rain. One of these she recognised as a battle cruiser, but lost contact in the gloom, and the enemy made good his escape.

The hope of bringing these two vital German ships to battle dominated all concerned, and the Commander-in-Chief put to sea at once with his whole fleet. When last seen the enemy was retiring to the eastward, and strong forces, including submarines, were promptly organised to intercept him in the North Sea. However, we could not ignore the possibility that having shaken off the pursuit the enemy might renew his advance to the westward and enter the Atlantic. We feared for our convoys, and the situation called for the use of all available forces. Sea and air patrols were established to watch all the exits from the North Sea, and a powerful force of cruisers extended this watch to the coast of Norway. In the Atlantic the battleship

Warspite

left her convoy to search the Denmark Strait and, finding nothing, continued round the north of Iceland to link up with the watchers in the North Sea. The

Hood,

the French battle cruiser

Dunkerque,

and two French cruisers were dispatched to Icelandic waters, and the

Repulse

and

Furious

sailed from Halifax for the same destination. By the twenty-fifth fourteen British cruisers were combing the North Sea with destroyers and submarines co-operating and with the battle-fleet in support. But fortune was adverse, nothing was found, nor was there any indication of an enemy move to the west. Despite very severe weather, the arduous search was maintained for seven days.