The Gathering Storm: The Second World War (75 page)

Read The Gathering Storm: The Second World War Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Western, #Fiction

5. What can they do against this? Obviously nets would be put across; but wreckage passing down the river would break these nets, and except at the frontier, they would be a great inconvenience to the traffic. Anyhow, when our mine fetched up against them, it would explode, breaking a large hole in the nets, and after a dozen or more of these explosions the channel would become free again, and other mines would jog along. Specially large mines might be used to break the nets. I cannot think of any other method of defence, but perhaps some may occur to the officers entrusted with this study.

6. Finally, as very large numbers of these mines would be used and the process kept up night after night for months on end, so as to deny the use of the waterway, it is necessary to bear in mind the simplification required for mass production.

The War Cabinet liked this plan. It seemed to them only right and proper that when the Germans were using the magnetic mine to waylay and destroy all traffic, Allied or neutral, entering British ports, we should strike back by paralysing, as we might well do, the whole of their vast traffic on the Rhine. The necessary permissions and priorities were obtained, and work started at full speed. In conjunction with the Air Ministry we developed a plan for mining the Ruhr section of the Rhine by discharge from airplanes. I entrusted all this work to Rear-Admiral FitzGerald, serving under the Fifth Sea Lord. This brilliant officer, who perished later in command of an Atlantic convoy, made an immense personal contribution. The technical problems were solved. A good supply of mines was assured, and several hundred ardent British sailors and marines were organised to handle them when the time should come. All this was in November, and we could not be ready before March. It is always agreeable in peace or war to have something positive coming along on your side.

| 8 |

Surface Raiders — The German Pocket Battleship

—

Orders of the German Admiralty

—

British Hunting Groups

—

The American Three-Hundred-Mile Limit

—

Offer of Our Asdics to the United States

—

Anxieties at Home

—

Caution of the “Deutschland” — Daring of the “Graf Spee”

— Captain Langsdorff’s Manoeuvres — Commodore Harwood’s Squadron off

the Plate — His Foresight and Fortune

—

Collision on December

13

— Langsdorff’s Mistake — The “Exeter” Disabled — Retreat of the German Pocket Battleship

—

Pursuit by “Ajax” and “Achilles”

—

The “Spee” Takes Refuge in Montevideo

—

My Letter of December

17

to the Prime Minister

—

British Concentration on Montevideo

—

Langsdorff’s Orders from the Fuehrer

—

Scuttling of the “Spee”

—

Langsdorff’s Suicide

— End of the First Surface Challenge to British Commerce

—

The “Altmark”

—

The “Exeter”

—

Effects of the Action off the Plate

—

My Telegram to President Roosevelt.

A

LTHOUGH

it was the U-boat menace from which we suffered most and ran the greatest risks, the attack on our ocean commerce by surface raiders would have been even more formidable could it have been sustained. The three German pocket battleships permitted by the Treaty of Versailles had been designed with profound thought as commerce-destroyers. Their six eleven-inch guns, their twenty-six-knot speed, and the armour they carried had been compressed with masterly skill into the limits of a ten-thousand-ton displacement. No single British cruiser could match them. The German eight-inch-gun cruisers were more modern than ours, and if employed as commerce-raiders, would also be a formidable threat. Besides this, the enemy might use disguised heavily armed merchantmen. We had vivid memories of the depredations of the

Emden

and

Koenigsberg

in 1914, and of the thirty or more warships and armed merchantmen they had forced us to combine for their destruction.

There were rumours and reports before the outbreak of the new war that one or more pocket battleships had already sailed from Germany. The Home Fleet searched but found nothing. We now know that both the

Deutschland

and the

Admiral Graf Spee

sailed from Germany between August 21 and 24, and were already through the danger zone and loose in the oceans before our blockade and northern patrols were organised. On September 3, the

Deutschland,

having passed through the Denmark Straits, was lurking near Greenland. The

Graf Spee

had crossed the North Atlantic trade route unseen and was already far south of the Azores. Each was accompanied by an auxiliary vessel to replenish fuel and stores. Both at first remained inactive and lost in the ocean spaces. Unless they struck, they won no prizes. Until they struck, they were in no danger.

The orders of the German Admiralty issued on August 4 were well conceived:

Task in the Event of War

Disruption and destruction of enemy merchant shipping by all possible means…. Enemy naval forces, even if inferior, are only to be engaged if it should further the principal task….

Frequent changes of position in the operational areas will create uncertainty and will restrict enemy merchant shipping, even without tangible results. A temporary departure into distant areas will also add to the uncertainty of the enemy.

If the enemy should protect his shipping with superior forces so that direct successes cannot be obtained, then the mere fact that his shipping is so restricted means that we have greatly impaired his supply situation. Valuable results will also be obtained if the pocket battleships continue to remain in the convoy area.

With all this wisdom the British Admiralty would have been in rueful agreement.

* * * * *

On September 30, the British liner

Clement,

of five thousand tons, sailing independently, was sunk by the

Graf Spee

off Pernambuco. The news electrified the Admiralty. It was the signal for which we had been waiting. A number of hunting groups were immediately formed, comprising all our available aircraft carriers, supported by battleships, battle cruisers, and cruisers. Each group of two or more ships was judged to be capable of catching and destroying a pocket battleship.

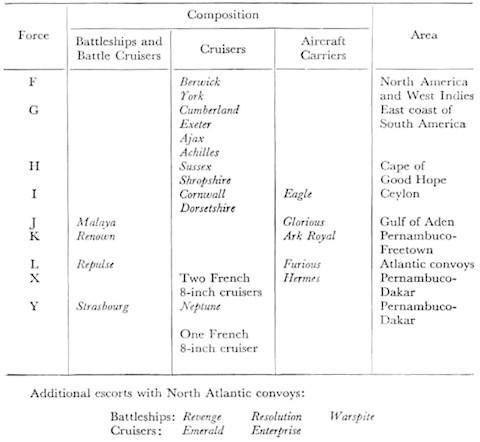

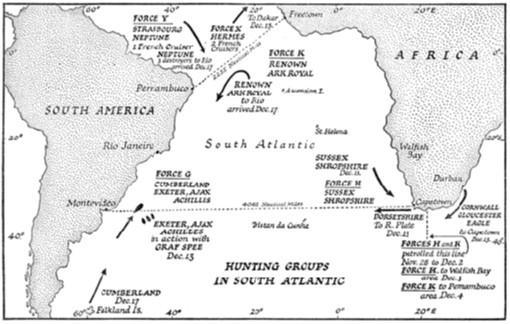

In all, during the ensuing months the search for two raiders entailed the formation of nine hunting groups, comprising twenty-three powerful ships. We were also compelled to provide three battleships and two cruisers as additional escorts with the important North Atlantic convoys. These requirements represented a very severe drain on the resources of the Home and Mediterranean Fleets, from which it was necessary to withdraw twelve ships of the most powerful types, including three aircraft carriers. Working from widely dispersed bases in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, the hunting groups could cover the main focal areas traversed by our shipping. To attack our trade the enemy must place himself within reach of at least one of them. To give an idea of the scale of these operations, I set out the full list of the hunting groups at their highest point on page 514.

* * * * *

Organisation of Hunting Groups — October

31, 1939

At this time it was the prime objective of the American Governments to keep the war as far from their shores as possible. On October 3, delegates of twenty-one American Republics, assembled at Panama, decided to declare an American security zone, proposing to fix a belt of from three hundred to six hundred miles from their coasts within which no warlike act should be committed. We were anxious to help in keeping the war out of American waters – to some extent, indeed, this was to our advantage. I therefore hastened to inform President Roosevelt that, if America asked all belligerents to respect such a zone, we should immediately declare our readiness to fall in with their wishes – subject, of course, to our rights under international law. We should not mind how far south the security zone went, provided that it was effectively maintained. We should have found great difficulty in accepting a security zone which was to be policed only by some weak neutral; but if the United States Navy was to take care of it, we should feel no anxiety. The more United States warships there were cruising along the South American coast, the better we should be pleased; for the German raider which we were hunting might then prefer to leave American waters for the South African trade route, where we were ready to deal with him. But if a surface raider operated from the American security zone or took refuge in it, we should expect either to be protected, or to be allowed to protect ourselves from the mischief which he might do.

At this date we had no definite knowledge of the sinking of three ships on the Cape of Good Hope route which occurred between October 5 and 10. All three were sailing homeward independently. No distress messages were received, and suspicion was only aroused when they became overdue. It was some time before it could be assumed that they had fallen victims to a raider.

The necessary dispersion of our forces caused me and others anxiety, especially as our main Fleet was sheltering on the west coast of Britain.

First Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff. | 21.X.39. |

The appearance of

Scheer

off Pernambuco and subsequent mystery of her movements, and why she does not attack trade, make one ask, did the Germans want to provoke a widespread dispersion of our surplus vessels, and if so, why? As the First Sea Lord has observed, it would be more natural they should wish to concentrate them in home waters in order to have targets for air attack. Moreover, how could they have foreseen the extent to which we should react on the rumour of

Scheer

in South Atlantic? It all seems quite purposeless, yet the Germans are not the people to do things without reason. Are you sure it was

Scheer

and not a plant, or a fake?

I see the German wireless boast they are driving the Fleet out of the North Sea. At present this is less mendacious than most of their stuff. There may, therefore, be danger on the east coast from surface ships. Could not submarine flotillas of our own be disposed well out at sea across a probable line of hostile advance? They would want a parent destroyer perhaps to scout for them. They should be well out of our line of watching trawlers. It may well be there is something going to happen, now that we have retired to a distance to gain time.

I should be the last to raise those “invasion scares,” which I combated so constantly during the early days of 1914/15. Still, it might be well for the Chiefs of Staff to consider what would happen if, for instance, twenty thousand men were run across and landed, say, at Harwich, or at Webburn Hook, where there is deep water close inshore. These twenty thousand men might make the training of Mr. Hore-Belisha’s masses very much more realistic than is at present expected. The long dark nights would help such designs. Have any arrangements been made by the War Office to provide against this contingency? Remember how we stand in the North Sea at the present time. I do not think it likely, but is it physically possible?