The Gathering Storm: The Second World War (79 page)

Read The Gathering Storm: The Second World War Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Western, #Fiction

* * * * *

Almost at this very moment (as we now know), German eyes were turned in the same direction. On October 3, Admiral Raeder, Chief of the Naval Staff, submitted a proposal to Hitler headed “Gaining of Bases in Norway.” He asked, “That the Fuehrer be informed as soon as possible of the opinions of the Naval War Staff on the possibilities of extending the operational base to the North. It must be ascertained whether it is possible to gain bases in Norway under the combined pressure of Russia and Germany, with the aim of improving our strategic and operational position.” He framed, therefore, a series of notes which he placed before Hitler on October 10.

In these notes [he wrote] I stressed the disadvantages which an occupation of Norway by the British would have for us: the control of the approaches to the Baltic, the outflanking of our naval operations and of our air attacks on Britain, the end of our pressure on Sweden. I also stressed the advantages for us of the occupation of the Norwegian coast: outlet to the North Atlantic, no possibility of a British mine barrier, as in the year 1917/18…. The Fuehrer saw at once the significance of the Norwegian problem; he asked me to leave the notes and stated that he wished to consider the question himself.

Rosenberg, the Foreign Affairs expert of the Nazi Party, and in charge of a special bureau to deal with propaganda activities in foreign countries, shared the Admiral’s views. He dreamed of “converting Scandinavia to the idea of a Nordic community embracing the northern peoples under the natural leadership of Germany.” Early in 1939, he thought he had discovered an instrument in the extreme Nationalist Party in Norway, which was led by a former Norwegian Minister of War named Vidkun Quisling. Contacts were established, and Quisling’s activity was linked with the plans of the German Naval Staff through the Rosenberg organisation and the German Naval Attaché in Oslo.

Quisling and his assistant, Hagelin, came to Berlin on December 14, and were taken by Raeder to Hitler, to discuss a political stroke in Norway. Quisling arrived with a detailed plan. Hitler, careful of secrecy, affected reluctance to increase his commitments, and said he would prefer a neutral Scandinavia. Nevertheless, according to Raeder, it was on this very day that he gave the order to the Supreme Command to prepare for a Norwegian operation.

Of all this we, of course, knew nothing. The two Admiralties thought with precision along the same lines in correct strategy, and one had obtained decisions from its Government.

* * * * *

Meanwhile, the Scandinavian peninsula became the scene of an unexpected conflict which aroused strong feeling in Britain and France, and powerfully affected the discussions about Norway. As soon as Germany was involved in war with Great Britain and France, Soviet Russia in the spirit of her pact with Germany proceeded to block the lines of entry into the Soviet Union from the west. One passage led from East Prussia through the Baltic States; another led across the waters of the Gulf of Finland; the third route was through Finland itself and across the Karelian Isthmus to a point where the Finnish frontier was only twenty miles from the suburbs of Leningrad. The Soviet had not forgotten the dangers which Leningrad had faced in 1919. Even the White Russian Government of Kolchak had informed the Peace Conference in Paris that bases in the Baltic States and Finland were a necessary protection for the Russian capital. Stalin had used the same language to the British and French Missions in the summer of 1939; and we have seen in earlier chapters how the natural fears of these small states had been an obstacle to an Anglo-French Alliance with Russia, and had paved the way for the Molotov-Ribbentrop Agreement.

Stalin had wasted no time; on September 24, the Esthonian Foreign Minister had been called to Moscow, and four days later his Government signed a Pact of Mutual Assistance which gave the Russians the right to garrison key bases in Esthonia. By October 21, the Red Army and air force were installed. The same procedure was used simultaneously in Latvia, and Soviet garrisons also appeared in Lithuania. Thus, the southern road to Leningrad and half the Gulf of Finland had been swiftly barred against potential German ambitions by the armed forces of the Soviet. There remained only the approach through Finland.

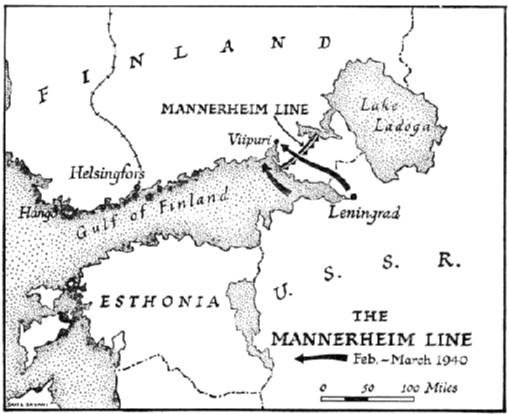

Early in October, Mr. Paasikivi, one of the Finnish statesmen who had signed the Peace of 1921 with the Soviet Union, went to Moscow. The Soviet demands were sweeping; the Finnish frontier on the Karelian Isthmus must be moved back a considerable distance so as to remove Leningrad from the range of hostile artillery. The cession of certain Finnish islands in the Gulf of Finland; the lease of the Rybathy Peninsula together with Finland’s only ice-free port in the Arctic Sea, Petsamo; and above all, the leasing of the port of Hango at the entrance of the Gulf of Finland as a Russian naval and air base, completed the Soviet requirements. The Finns were prepared to make concessions on every point except the last. With the keys of the Gulf in Russian hands the strategic and national security of Finland seemed to them to vanish. The negotiations broke down on November 13, and the Finnish Government began to mobilise and strengthen their troops on the Karelian frontier. On November 28, Molotov denounced the Non-Aggression Pact between Finland and Russia; two days later, the Russians attacked at eight points along Finland’s thousand-mile frontier, and on the same morning the capital, Helsingfors, was bombed by the Red air force.

The brunt of the Russian attack fell at first upon the frontier defences of the Finns in the Karelian Isthmus. These comprised a fortified zone about twenty miles in depth running north and south through forest country deep in snow. This was called the “Mannerheim Line,” after the Finnish Commander-in-Chief and saviour of Finland from Bolshevik subjugation in 1917. The indignation excited in Britain, France, and even more vehemently in the United States, at the unprovoked attack by the enormous Soviet Power upon a small, spirited, and highly civilised nation, was soon followed by astonishment and relief. The early weeks of fighting brought no success to the Soviet forces, which in the first instance were drawn almost entirely from the Leningrad garrison. The Finnish Army, whose total fighting strength was only about two hundred thousand men, gave a good account of themselves. The Russian tanks were encountered with audacity and a new type of hand-grenade, soon nicknamed “The Molotov Cocktail.”

It is probable that the Soviet Government had counted on a walk-over. Their early air raids on Helsingfors and elsewhere, though not on a heavy scale, were expected to strike terror. The troops they used at first, though numerically much stronger, were inferior in quality and ill-trained. The effect of the air raids and of the invasion of their land roused the Finns, who rallied to a man against the aggressor and fought with absolute determination and the utmost skill. It is true that the Russian division which carried out the attack on Petsamo had little difficulty in throwing back the seven hundred Finns in that area. But the attack on the “Waist” of Finland proved disastrous to the invaders. The country here is almost entirely pine forests, gently undulating and at the time covered with a foot of hard snow. The cold was intense. The Finns were well equipped with skis and warm clothing, of which the Russians had neither. Moreover, the Finns proved themselves aggressive individual fighters, highly trained in reconnaissance and forest warfare. The Russians relied in vain on numbers and heavier weapons. All along this front the Finnish frontier posts withdrew slowly down the roads, followed by the Russian columns. After these had penetrated about thirty miles, they were set upon by the Finns. Held in front at Finnish defence lines constructed in the forests, violently attacked in flank by day and night, their communications severed behind them, the columns were cut to pieces, or, if lucky, got back after heavy loss whence they came. By the end of December, the whole Russian plan for driving in across the “Waist” had broken down.

Meanwhile, the attacks against the Mannerheim Line in the Karelian Peninsula fared no better. North of Lake Ladoga a turning movement attempted by about two Soviet divisions met the same fate as the operations farther north. Against the Line itself a series of mass attacks by nearly twelve divisions was launched in early December and continued throughout the month. The Russian artillery bombardments were inadequate; their tanks were mostly light, and a succession of frontal attacks were repulsed with heavy losses and no gains. By the end of the year, failure all along the front convinced the Soviet Government that they had to deal with a very different enemy from what they had expected. They determined upon a major effort. Realising that in the forest warfare of the north they could not overcome by mere weight of numbers the superior tactics and training of the Finns, they decided to concentrate on piercing the Mannerheim Line by methods of siege warfare in which the power of massed heavy artillery and heavy tanks could be brought into full play. This required preparation on a large scale, and from the end of the year fighting died down all along the Finnish Front, leaving the Finns so far victorious over their mighty assailant. This surprising event was received with equal satisfaction in all countries, belligerent or neutral, throughout the world. It was a pretty bad advertisement for the Soviet Army. In British circles many people congratulated themselves that we had not gone out of our way to bring the Soviets in on our side, and preened themselves on their foresight. The conclusion was drawn too hastily that the Russian Army had been ruined by the purge, and that the inherent rottenness and degradation of their system of government and society was now proved. It was not only in England that this view was taken. There is no doubt that Hitler and all his generals meditated profoundly upon the Finnish exposure, and that it played a potent part in influencing the Fuehrer’s thought.

All the resentment felt against the Soviet Government for the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact was fanned into flame by this latest exhibition of brutal bullying and aggression. With this was also mingled scorn for the inefficiency displayed by the Soviet troops and enthusiasm for the gallant Finns. In spite of the Great War which had been declared, there was a keen desire to help the Finns by aircraft and other precious war material and by volunteers from Britain, from the United States, and still more from France. Alike for the munition supplies and the volunteers, there was only one possible route to Finland. The iron-ore port of Narvik with its railroad over the mountains to the Swedish iron mines acquired a new senti mental if not strategic significance. Its use as a line of supply for the Finnish armies affected the neutrality both of Norway and Sweden. These two states, in equal fear of Germany and Russia, had no aim but to keep out of the wars by which they were encircled and might be engulfed. For them this seemed the only chance of survival. But whereas the British Government were naturally reluctant to commit even a technical infringement of Norwegian territorial waters by laying mines in the Leads for their own advantage against Germany, they moved upon a generous emotion, only indirectly connected with our war problem, towards a far more serious demand upon both Norway and Sweden for the free passage of men and supplies to Finland.

I sympathised ardently with the Finns and supported all proposals for their aid; and I welcomed this new and favourable breeze as a means of achieving the major strategic advantage of cutting off the vital iron-ore supplies of Germany. If Narvik was to become a kind of Allied base to supply the Finns, it would certainly be easy to prevent the German ships loading ore at the port and sailing safely down the Leads to Germany. Once Norwegian and Swedish protestations were overborne for whatever reason, the greater measures would include the less. The Admiralty eyes were also fixed at this time upon the movements of a large and powerful Russian ice-breaker which was to be sent from Murmansk to Germany, ostensibly for repairs, but much more probably to open the now-frozen Baltic port of Lulea for the German ore ships. I, therefore, renewed my efforts to win consent to the simple and bloodless operation of mining the Leads, for which a certain precedent of the previous war existed. As the question raises moral issues, I feel it right to set the case in its final form as I made it after prolonged reflection and debate.