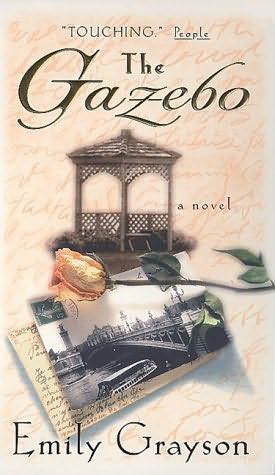

The Gazebo: A Novel

Read The Gazebo: A Novel Online

Authors: Emily Grayson

The

Gazebo

Emily Grayson

To my children

With many thanks to

Lisa Queen and Claire Wachtel

for all their help and encouragement

T

HE MAN WITH

the silver hair had been standing in the doorway even before she knew he was there. How long, she couldn’t say. Abby just looked up, and there he was, not knocking. He hadn’t asked for her at the front desk, or someone would have called her. He hadn’t asked for directions down the hall to her office, or someone would have accompanied him. Instead, he’d simply found her, as if he knew his way around the place, and then he stood there, as if he were willing to wait forever.

“Yes?” she said to him, bending back to the work on her desk.

“Forgive the interruption,” the man said.

“But I have something that may interest you.”

“I’m sorry. I’m very busy.” Abby kept reading the printout of a page proof and entering

her corrections into the computer on the edge of her desk. She didn’t want to appear impolite, but this was a newspaper; there were deadlines. Show up unannounced in the editor’s office and you couldn’t expect her undivided attention. “So,” she said, checking, typing, “can this wait?”

“I’m afraid not,” he said.

She glanced up. The man in her doorway was wearing a light linen jacket and setting a very worn but well–made briefcase down on the floor. He didn’t seem to be from around here, yet she couldn’t be sure. Abby hesitated, then returned to her work.

“This will take only a minute,” he went on.

“You

are

Abby Reston, aren’t you?”

She nodded, not looking up.

“I have a story I’d like you to know about,” he said. “Something you might be interested in printing in the

Ledger

. A human interest story, I guess.”

It was just as she’d thought. The

Ledger

was an institution of sorts in these parts, dating back to the middle of the previous century, and since she’d taken over as editor six months earlier Abby had often found herself

on the receiving end of a faithful reader’s suggestion for a “wonderful” article: missing wedding rings, the death of a beloved schnauzer, feuds between neighbors. Usually, what someone thought was perfect for a newspaper turned out to be too personal, too particular, or simply not interesting enough. “You should talk to one of our reporters,” Abby told him. “I can put you in touch with—”

“No,” the man said, interrupting.

Abby glanced up again.

“It’s a story that needs to be written by someone who can really write. I think this story is for you to write,” he continued. “Maybe I could tell it to you, and then you can decide.”

She looked at the computer screen, its cursor blinking impatiently, then at the unmoving man in the doorway. “If you can say what it’s about in a sentence or two,” she said.

The man nodded. “It’s a love story,” he said.

“Well, we could use more of those in the world,” said Abby. She leaned back in her chair, its wooden joints heaving slightly.

“It’s about myself,” he continued. “I’m sorry, I haven’t even given you my name. It’s Martin Rayfiel.”

He seemed to be studying her for a response. She shook her head slightly, gave a mild shrug. “Should I know you?”

He smiled, almost to himself. “Not really,” he said. “It’s just that the name sometimes used to get a reaction around here.” Then he drew himself straight, getting down to business. “I’ll make this quick.” He took a breath and began. “Every year at dusk on May twenty–seventh, I meet the woman I love in the gazebo in the town square. It’s the only time we have a chance to be together.” He inclined his chin in the direction of Abby’s screen window. She turned in her chair to follow his gaze across the street to the town square, and across the town square to the gazebo, where a small boy was sitting with his mother, unhappily submitting to her efforts to clean his face with a wet wipe.

“Once a year,” she said, and he nodded. Not a wife, then, Abby thought. A lover? But then why tell Abby? And why ask Abby to tell the world—or Longwood Falls, anyway? He’d succeeded in beginning to arouse her curiosity, but that was nothing, Abby knew; it was her job to be curious. The question was

whether anyone else would care about this apparently private annual event. Abby peered down at the day–at–a–glance calendar on her desk. “Tomorrow’s the twenty–seventh,” she said to him.

He nodded again. “Claire and I have been meeting on May twenty–seventh at the gazebo for quite some time. Actually, we’ve been doing it for fifty years. And we never missed a year.”

Fifty years

. Abby had only just turned thirty–five; she could barely imagine being alive for such a long time, let alone having loved someone for so long. She looked again at this man, closely, as if for the first time. Martin Rayfiel was not young, but his appearance was striking, and young in its own way. His hair was slightly long and shot through with silver, brushed back off his face as though with an impatient hand. He was probably in his late sixties, around the age her father would have been, she realized, and then when she tried to picture Martin Rayfiel as a much younger man, his silver hair an uninterrupted black, his long features unlined, his slender hands tracing the face of a young woman—when she

tried to picture him as a young man just falling in love—it was her father’s face that came to mind. And then it wasn’t, because Abby couldn’t imagine her father, however much he’d loved her mother up to the moment of his death seven months earlier, in the grip of something approximating passion.

“Excuse me? Abby?” It was Kim, the newspaper’s combination classified ad saleswoman and receptionist, suddenly hovering behind Martin Rayfiel in the office doorway. She was a small, overly caffeinated young woman in a pink headband, and she was shifting from foot to foot. Martin stepped aside, and Kim said, “I have to get those forms in by this afternoon?”

At the moment, Abby couldn’t remember what forms Kim was talking about, but she quickly apologized and told Kim that of course she’d be right with her. “I’m sorry,” Abby said to Martin. “I’d like to hear the rest, but …” and she gestured toward Kim, her computer, the obediently waiting cursor.

“That’s all right,” Martin Rayfiel said softly. “We’ll just chalk it up to bad timing on my part.” This, too, seemed to amuse him in some private way. “Well, thank you. I tried anyway.

You’ve been very gracious, and I appreciate it.” He bowed his head once, and then he picked up his briefcase and walked out the door, slipping away as quietly as he had come.

Abby wanted to call out to him, but what would she say? Even if she could find the time to hear the rest of his story, she still didn’t know whether she would want it for the newspaper. Yet it didn’t feel right to let him leave without saying something to this man who had experienced love for half a century and wanted to tell everyone about it. It wasn’t until Kim had laid out the paperwork on the desk and left the office, and Abby had turned back toward the window and watched Martin Rayfiel disappear across the town square, passing the gazebo without a glance, his linen suit lifting as if a simple spring breeze might carry him to another county, that Abby knew what she wished she’d called out to him.

“Happy anniversary,” she said.

The next day Abby Reston went about the business of putting together another edition of the

Longwood Falls Ledger

. She oversaw a staff meeting, wrote an editorial on the debate over

school taxes, edited copy, drank too much coffee, forgot to eat lunch, pulled herself from the depths of a late–afternoon blood–sugar low with the help of two Almond Joys, hated herself a little for eating two candy bars instead of the salad she’d stashed in the office mini–fridge that morning, and finally, at promptly 5

P.M.

, pressed the key on the computer that dispatched the May 28, 1999, edition of the paper off to the printer and into the world.

Which made today May 27. Abby got up from her desk and stretched her arms above her head, feeling something inside her lightly pop and crack. For the first time all day she thought about the enigmatic man who had paid her a visit the previous afternoon, and she thought about the one day a year that, for some reason, he and a woman named Claire were able to see each other. Abby glanced out the window at the white gazebo in the distance, as if Martin and Claire might have materialized there. But then she remembered:

dusk

, he’d said. It wasn’t quite dusk yet, and even if it were, Abby didn’t know what it was she hoped she might find outside her window except two people in love—not exactly an uncommon

sight on the lawn of a town square.

So she got up and left the office, quickly walking the three blocks to her small clapboard house on Alder Lane. It was a luxury to be able to visit her daughter during the workday—something she’d never been able to do when she was a magazine editor in New York City. Now she let herself into her house, where Miranda, who was six, was sitting at the kitchen table, being served a plate of chicken nuggets in the shapes of various dinosaurs by the housekeeper, Mrs. Frayne.

“Mommy, look. Triceratops,” Miranda announced, holding up a piece of chicken, and then she leaned across the table to embrace her mother. Abby inhaled the sweetness of her daughter: a chocolate milk smell, and a fruity children’s shampoo.

Miranda talked of school, and Abby listened. Miranda’s class had visited a dairy farm that day, and each child had personally given a tug at the udders of an oblivious cow, a fact that had Miranda chattering away. Abby sat down and leaned forward, her elbows on her knees, as if she was studying her daughter’s face, memorizing it for the long evening ahead

at the office. Miranda had her father’s coloring, the Irish setter shade of brown hair and dark brown eyes. It was an odd punishment to be reminded of Sam whenever she looked at Miranda, but there it was, unavoidable.

Abby had never thought it would be easy to raise a child alone, but she hadn’t realized how hard it would be to continually

leave

Miranda. There were always good–byes: another meeting Abby had to run, another deadline. It had been just as bad in New York City, and the only times she and her daughter had a chance to really be together were on weekends, or at night after Mrs. Frayne went home to the apartment she rented in a house two blocks away, when they would sprawl across Abby’s big bed and talk for a long time. Abby would braid Miranda’s hair and softly read to her. There was no pleasure as intense as this one, she would think to herself.

But now she had only a little while to catch a glimpse of Miranda and hear about her day, and then it was time to get back to the office. She touched her daughter’s shoulder and got ready to leave. “See you, Mom,” Miranda said, smiling, and then immediately dipped her

head down to continue reading a book about a girl and her pet chameleon.

“Oh, Abby?” said Mrs. Frayne. “I almost forgot. Someone called before, from New York City, said his name was Nick, and that he just wanted to say hi and see how you and Miranda were doing.”

“Nick the doctor?” said Miranda, looking up and appearing interested, and Abby nodded.

Nick Kelleher had left a few messages since she’d moved here, and they’d spoken twice, briefly, catching each other up on their lives, flirting in a light way, but she had never given him any real encouragement, never let him think that she was interested in him. Still, for some reason, he kept calling.

“He sounded nice,” Mrs. Frayne said wistfully.

“He

is

nice,” said Abby, and then she turned and headed for the door, abruptly ending the conversation. “See you later,” she said to her housekeeper and her daughter before they had a chance to say anything more about Nick.

But on her way back to the newspaper, the sky growing dim, the workday ending for

most people though not for her, dusk really arriving, Abby paused on the green. It was true that she had to get back to work, but maybe this

was

work, she reminded herself: a story she’d been invited to write, the story of Martin Rayfiel and a woman named Claire. A love story, he’d said.

Abby selected a bench near the gazebo—not so close that she would seem intrusive, but close enough so that in a little while she would discreetly be able to observe the … what? Reunion? Rendezvous? The gazebo seemed an unlikely setting for something illicit: open and airy and more than a little old–fashioned. But maybe that was why they’d chosen it. Who would suspect that two people meeting in the most public place in town were trying to hide something? In fact, as she studied it now, Abby realized how little she’d ever thought about the gazebo. It was simply

there

. She had never before examined the delicacy of its architecture, the gingerbread wood painted white—an octagon, she noticed, counting—or the roof coming to a point that punctuated the sky beyond. It was an evocative if frivolous structure, yet apparently it had meaning to at least two people.

Abby leaned back against the bench and began her vigil. She saw a heavy, elderly woman in a cardigan and too much bright makeup, and she hoped this wasn’t Claire. It wasn’t; the woman kept walking. Good, Abby thought. Then another woman, red–haired and pretty and wearing a zippered jogging suit, approached and actually sat in the gazebo, but she looked too young to have been meeting Martin there for fifty years. In a moment the woman was joined by two other women friends, both of them in jogging suits, too, and the three of them stood, did a few leg stretches, and jogged off together. Then no one approached the gazebo.

The streetlights around the square popped on all at once, followed a moment later by the antique lamps along the lanes in the square. It was an appealing setting, and all of Longwood Falls, New York, was like that: idyllic in many ways, safe and intimate and scenic, full of greenery and ponds and winding roads lined by low fences. Yet in the end it had not been enough to hold her here. Like so many of her friends the summer after high school graduation, Abby Reston had boarded a southbound

train to New York City with barely any regret.

Now she was back. When her father died of a sudden heart attack last fall, Abby had returned home for the funeral, and to help her mother. She’d brought Miranda and their housekeeper, and a few days evolved into a few weeks. Then she ended up staying on, moving back here, and taking over her father’s job as editor of the

Ledger

, settling herself and her daughter and even their housekeeper, who hadn’t loved the city anyway, into this very different life. Her coworkers said she worked excessively, and of course, they were right. Some of it was simply learning to readjust to the pace of a small town again. At the women’s fashion magazine in Manhattan where she’d worked as a features editor, midnight closings were common, almost an excuse for a frenzied slumber party atmosphere of pizza and wine and complaints and exhaustion. Mrs. Frayne had often had to stay very late in the apartment back then, and Abby would give her cab fare and send her home in the dead of night. “You work too much,” the housekeeper had bluntly said as she shrugged into her coat at 1

A.M.

, a comment that would

be echoed again and again by various people. But some of Abby’s approach to work was hereditary. It was a trait she had inherited from her father, and sometimes, sitting behind the same heavy birch desk that Tom Reston had occupied for forty years, Abby couldn’t help wondering if her father had found solace where she did, in moments of quiet efficiency and the formidable accumulation of facts.