The German War (81 page)

Authors: Nicholas Stargardt

Berliners swimming near the remains of the Zoo bunker, 1945.

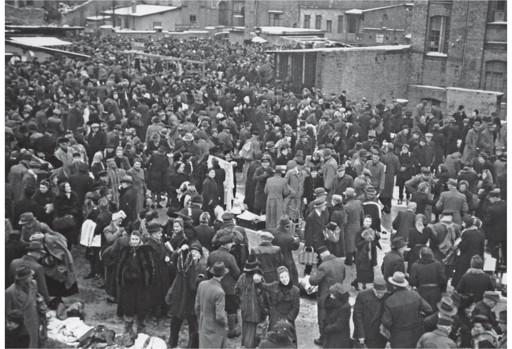

Black market in Berlin.

Missing children poster.

Cellar dwelling in Hamburg for two families, July 1947.

Liselotte Purper: rehabilitation of a war amputee.

As the bombing of the cities began again in the autumn of 1944, Lisa de Boor found strength in German culture. When she learned that the house in which Goethe was born had been destroyed, she told herself that the writer ‘can only be sought and found through what he gave to the world, through

Faust, Wilhelm Meister,

in

Poetry and Truth

and in the

West-East Divan.

All that cannot be destroyed by terror-flyers when one has already imbibed its substance, treasured it and brought it to life.’ Hoping for a quick defeat and the end of Nazism, as she had since 1939, she turned to her spiritual guide, Rudolf Steiner, who had founded his Anthroposophical Society on an esoteric reading of Goethe. For all her humanitarian internationalism, the Steiner quotes which she found apposite now had a strong ring of German nationalism: ‘It belongs to the most miraculous stroke of fate that the German always brings his inner strength, the power of his spirit, to fruition when the trends of the outward world are most unfavourable. As with her admiration for Hölderlin and Ernst Jünger, so here too de Boor found a sense of national identity in the words of a writer with no connection to National Socialism. On 25 November, she commemorated Remembrance Sunday by finally writing the poem she had long planned in memory of the German war dead:

Faust, Wilhelm Meister,

in

Poetry and Truth

and in the

West-East Divan.

All that cannot be destroyed by terror-flyers when one has already imbibed its substance, treasured it and brought it to life.’ Hoping for a quick defeat and the end of Nazism, as she had since 1939, she turned to her spiritual guide, Rudolf Steiner, who had founded his Anthroposophical Society on an esoteric reading of Goethe. For all her humanitarian internationalism, the Steiner quotes which she found apposite now had a strong ring of German nationalism: ‘It belongs to the most miraculous stroke of fate that the German always brings his inner strength, the power of his spirit, to fruition when the trends of the outward world are most unfavourable. As with her admiration for Hölderlin and Ernst Jünger, so here too de Boor found a sense of national identity in the words of a writer with no connection to National Socialism. On 25 November, she commemorated Remembrance Sunday by finally writing the poem she had long planned in memory of the German war dead:

Now gathering on the other side

The young, the beloved dead,

They went silently in black boats

And looked gravely back to this side,

At the fiery glow on our shores.

With no word of complaint, silently they went.

But their bright footprints remain

And words – their legacy – flutter,

Inwardly directing those who love them

To do their duty to the dead.

34

Although Marburg itself had not yet been bombed, Lisa de Boor knew that it was now only a matter of time before the war caught up with her too. She reread Thomas à Kempis and the last letter from a painter who had gone missing in action in Russia. Ever practical, she busied herself with drying fruit, and making up beds for the steady stream of friends fleeing from the west. As she waited for news of her daughter in Gestapo custody and met a mother whose own daughter had been killed while serving in a flak battery, Lisa asked herself, ‘What plans does the divine world have for the German people that it lays such heavy trials upon it?’

35

35

When Irene Guicking wrote to Ernst, her language was more homespun: ‘This war puts us through such a hard test.’ Frustrated by their separation, she found solace in the verse: ‘Let him be tested, who binds himself for ever.’ During the day, she had her hands full with their two small children but when she went to bed alone she had time to dwell on how much she missed him. She comforted herself with memories of their courtship but she could not conceal her fear: ‘I love you so. But then these painful thoughts fill me. You are a man. You love me above all. But all the same, how can you manage the desires which swirl in your head? I dare not think further. You are a man, after all.’ By contrast, her tone when she told Ernst that their flat in Giessen had been bombed was quite light: she and the children had long since moved to the relative safety of her parental home in Lauterbach.

36

36

On 4 and 5 November 1944, August Töpperwien’s home town of Solingen was bombed, the second raid destroying the town centre. Margarete wrote to her husband that she believed that 6,000 people had died; their house and furniture had survived largely intact. She and their 16-year-old son Karl Christoph had managed to reach the safety of the Lower Saxon countryside, humping their eiderdowns, rucksacks, suitcases and bags on overcrowded night trains and through waiting rooms full of exhausted soldiers and civilians. She was grateful simply to have ‘the hell of the west’ behind them, and found it incomprehensible ‘how people here cope with their overstrung nerves in the long run . . . Before each lunch we had to go to the cellar. And yet life goes on.’

37

37

As Liselotte Purper counted the ‘jewels’ of German cities destroyed by Allied air attacks – Strasbourg, Freiburg, Vienna, Munich, Nuremberg, Braunschweig, Stuttgart, ‘not to mention our Hamburg’ – she was filled with impotent rage at ‘the global criminal conspiracy’ which revealed ‘such a bottomless hatred, such a fanatical will to destroy as there never has been in the world. They know not what they do! . . . One day perhaps – if the veil of their senseless rage falls from their eyes – they may look with distress on what they have done.’ It was a different tone from her defiant letter of September, proclaiming that ‘Berlin remains Berlin’. ‘And us?’ she asked. ‘We are proud but powerless. If we had wings again . . .’

38

38

On the night of 12 September, the RAF returned to Stuttgart. In 31 minutes, they released 75 heavy mines, 4,300 high explosive bombs and 180,000 incendiaries over the old town centre, utterly destroying a 5-kilometre-square area. It was a repeat of the raids of 29 July, which had taken off many roofs and caused widespread fires in the city. This time, the heavy, late-summer air helped to ignite a firestorm in the steep-sided valley. As in Rostock, Hamburg and Kassel, many of those trying to flee were immolated by the flames. Many of the city’s air raid shelters rapidly overheated too. An estimated 1,000 people were killed, many of them from carbon monoxide gases seeping into the cellars of their blocks of flats where they had taken refuge.

39

39

The loss of France and Belgium meant that German forward fighter bases had become Allied airfields. With the loss of flak batteries and warning systems along the Channel coast, the British and American bomber fleets were now free to pick out targets that had never been hit before, and with little warning. From a strategic point of view, the bombing of the Ruhr, Hamburg and Berlin from March 1943 to March 1944 had marked the most important single phase of the bombing war. But the continued expansion of the British and American bomber fleets allowed them to carry fourteen times the payload of bombs and target them with six times the accuracy of 1941–42. Over half the total tonnage of bombs dropped on Germany rained down during the last eight months of the war.

40

40

The result was a death toll that stood no comparison with the previous phase of the air war. In Darmstadt, a firestorm was unleashed on the night of 11 September 1944, killing 8,494 people: their dead on this single night outstripped all the bombing casualties in Essen of the entire war. In Heilbronn, 5,092 were killed on the night of 5 December; on 16 December, some 4,000 lost their lives in Magdeburg. Over half the German civilians killed in the air war died after August 1944: 223,406 of an estimated 420,000 for the duration of the war.

41

41

Alongside the scale of the firestorms, the element of surprise accounted for a disproportionate number of the civilians killed in these raids. The populations of the cities which had been most frequently bombed, like Essen, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Kassel, Hamburg and Berlin, had had years to learn when it was dangerous to be out on the streets and where they could take shelter on their way to work. In Munich, Augsburg, Stuttgart, Vienna and Salzburg, people now had to adjust much faster, under far worse conditions. There was neither time nor materials to build new bunkers in cities that were being attacked for the first time. As the Allies targeted areas of the Reich which until now had served as centres of evacuation, Germans found that nowhere was truly safe.

As the air war worsened, rumours about Germany’s ‘new weapons’ centred on what was most obviously lacking – fighter planes. ‘The view is widespread and general that unless the enemy control of the air can be broken, no change in the fortunes of war can be brought about,’ ran a national report to the Propaganda Ministry in November. The rumours were not baseless: a squadron equipped with the Me 262 jet fighter was training at this time and even fought on a few occasions between August and November but, beset with chronic engine failures, it would not enter active service till the New Year. Engineers used all their skills in designing new models of jet aircraft, including Alexander Lippisch’s ramjet, the first model with a revolutionary delta wing. But Germany was now cut off from its Turkish and Portuguese supplies of chrome, wolfram and bauxite, so that production of high-grade steel alloys and aluminium could only continue from existing stocks. In early September, the USAAF carried out three devastating raids on synthetic oil plants, the Luftwaffe’s lifeline, setting the scene for a final shift in the strategic control of German airspace. Lack of aero fuel curtailed available flying time, which meant that new, under-trained pilots were sent into combat against overwhelming odds. In the second half of 1944, the Luftwaffe was effectively destroyed, losing 20,200 planes.

42

42

In this febrile atmosphere that veered precipitously between hope and helplessness, Goebbels launched a new propaganda offensive about ‘Bolshevik terror’. It had the same ingredients as the Katyn publicity of April and May 1943; except this time the victims were not Polish officers but German civilians. During the Soviet incursion into East Prussia in October 1944, two tank battalions had taken the small village of Nemmersdorf. They held it and its bridge for two days, 21–23 October, before retreating in the face of Wehrmacht counter-attacks. Most of the village’s 637 inhabitants got away, some of them waved through by Soviet troops after they had occupied the village. Some of the occupiers and occupied established normal relations – food was accepted with thanks and broken conversations were held – but elsewhere Germans were beaten, robbed, raped or killed. When German troops retook the village, Volkssturm men gathered the corpses of 26 civilians and laid them in an open grave in the village cemetery. The news spread like wildfire and, the next day, Heinrich Himmler’s personal physician, Professor Dr Karl Gebhardt, arrived along with several commissions from the Party, SS and police. On 25 October, a unit of military police arrived and conducted its own search, finding no further bodies. The 13 women, 5 children and 8 men were raised from the open grave and laid out on the ground so that they could be photographed, identified and examined by medical personnel. They found that, apart from the mayor, most of the men and women killed were elderly and had been executed by shots to the head. Although they suspected rape only in the case of one of the younger women, the photographers suggested otherwise, taking pictures of the female victims – who had already been moved at least twice – with their skirts raised and their stockings down. It was the kind of thing that Gebhardt, who combined serving as President of the German Red Cross with conducting experiments on female concentration camp prisoners, may well have ordered before the photographers arrived.

43

43

Other books

To Lie with Lions by Dorothy Dunnett

Twelve Hours by Leo J. Maloney

Thirty-Three Teeth by Colin Cotterill

Dead of Veridon by Tim Akers

Christmas With Tiffany by Carolynn Carey

Counterpart by Hayley Stone

Shadow of Perception by Kristine Mason

A to Z of You and Me by James Hannah

The Trouble with Marrying a Movie Star by Willett, ZN

The Night Eternal by Guillermo Del Toro, Chuck Hogan