The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 (2 page)

Read The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 Online

Authors: Robert Gellately

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Law, #Criminal Law, #Law Enforcement, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #European, #Specific Topics, #Social Sciences, #Reference, #Sociology, #Race Relations, #Discrimination & Racism

It would be impossible to name all those archivists who helped me, but I would like to make special mention of several. Dr Hermann Rumschottel pointed out where I could find important materials not only in Munich, but in other archives in Bavaria as well. In the Wiirzburg archive I received the kindest co-operation from Dr Siegfried Wenisch. His colleagues in the readingroom responded with good cheer (most of the time) to my repeated requests for more and more files. They never made me feel guilty about my Aktenhunger, and I thank them for indulging what Dominick LaCapra would call my archival fetishism. In the Dusseldorf archive I was warmly received by Dr Anselm Faust, who assisted my work. At the federal archives in Koblenz Dr Wilhelm Lenz has provided both help and encouragement, and his friendship and hospitality over the years make me look forward to a return visit to Koblenz.

Some of the material in Chapters 2 and 5 is also dealt with in an article 'The Gestapo and German Society: Political Denunciation in the Gestapo Case Files', which has been published in the Journal of Modern History (December 1988). Mary Van Steenberg, the managing editor of the journal, offered numerous suggestions for improving that piece and I want to record my gratitude here. One of the anonymous readers of the article asked several challenging questions. He turned out to be Gerald Feldman, and without wishing to hold him responsible for the views expressed in this book, I want to thank him for an especially probing analysis of the paper. The book's organization was influenced by his comments and queries.

At various times and places I have profited from discussions with colleagues. I owe thanks to Sarah Gordon for pointing out the importance of Gestapo case-files as social-historical sources, and for discussions at the very earliest stages of this project. As it has turned out, I have emphasized different themes and reached different conclusions, but I am sure we share common concerns about the history of racial persecution. I am grateful to my friend and colleague Gary Owens, who never failed to lend me a sympathetic ear as I struggled to find direction for this book. Lawrence Stokes of Dalhousie University has helped me from start to finish, and has been a constant source of information. Michael Kater of York University offered both criticism and encouragement on several occasions, and I certainly benefited from both. I am deeply indebted to Marie Fleming. I like to think my prose offered her a chance to hone her considerable abilities for spotting sloppy logic and dubious reasoning. She got plenty of practice in reading through the manuscript, and has saved me from countless infelicities.

I would also like to thank Tim Mason, William Allen, Rudy Koshar, Barbara Lane, Christopher Browning, Claudia Koonz, Kurt Duwell, Michael Geyer, Geoff Eley, Richard Bessel, Tom Childers, Jane Caplan, Marion Kaplan, Peter Hayes, Otto Dov Kulka, Hans Mommsen, Ulrich Herbert, Konrad Jarausch, Walter Struve, Eberhard Kolb, Reinhard Rurup, Lutz Niethammer, Detlev Peukert, Peter Alter, Gerhard Hirschfeld, Charles Maier, Czeslaw Luczak, Klaus Drobisch, Roland Flade, and Sybil Milton. I am grateful to John Was for improvements to the manuscript during copy-editing.

This book could not have been written without the support of Huron College and the financial assistance of grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Bonn) also provided funds at crucial times. It is a pleasure to acknowledge that support.

Official German guide-lines on accessibility to the archives, and especially Gestapo case-files, require that persons be referred to only in 'strictly anonymous forms'. Accordingly, the names of persons mentioned in the book from the Gestapo case-files and other archival sources have been changed. An exception has been made in Chapter 6, in the case of use Sonja Totzke, for reasons that will become evident. Members of the Gestapo and other Nazi officials of various kinds are not protected by the guide-lines and are referred to by their real names.

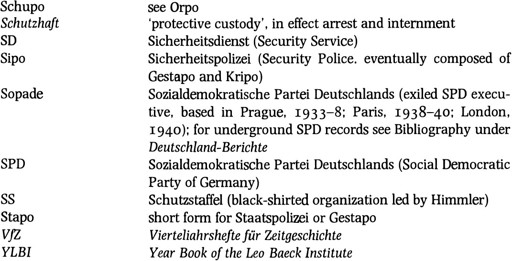

Abbreviations and Glossary

xiii

Introduction

1

1. THE GESTAPO

i. The Emergence of the Gestapo

21

2. Local Organization of the Gestapo and Police Network

44

II. GERMAN SOCIETY

3. Wurzburg and Lower Franconia before 1933

79

4. Anti-Jewish Actions in Lower Franconia after 1933

101

III. ENFORCING RACIAL POLICY

5. The Gestapo and Social Co-operation: The Example of Political Denunciation

130

6. Racial Policy and Varieties of Non-Compliance

159

7. Compliance through Pressure

185

8. 'Racially Foreign': Racial Policy and Polish Workers

215

Conclusion

253

Epilogue

262

Bibliography

267

Index

287

i. Bavaria, 1933 (excluding the Palatinate)

xv

2. Lower Franconia

xvi

i. Proceedings of the Dusseldorf Gestapo 1933-1945

47

2. Causes of the Initiation of a Proceeding with the Dusseldorf Gestapo (1933-1944)

135

3. Causes of Initiating Cases of `Race Defilement' and `Friendship to Jews' in the Wurzburg Gestapo (1933-1945)

162

4. Accusations of 'Race Defilement' and 'Friendship to Jews' in the Wizrzburg Gestapo Case-Files (1933-1945)

164

For archival abbreviations see the first section of the Bibliography.

MAP I Bavaria, 1933 (excluding the Palatinate)