The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 (30 page)

Read The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy 1933-1945 Online

Authors: Robert Gellately

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Law, #Criminal Law, #Law Enforcement, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #European, #Specific Topics, #Social Sciences, #Reference, #Sociology, #Race Relations, #Discrimination & Racism

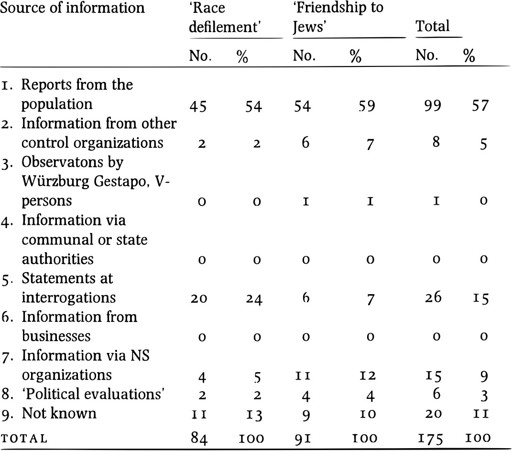

TABLE 3. Causes of Initiating Cases of 'Race Defilement' and 'Friendship to Jews' in the Wurzburg Gestapo (1933-1945)

Source: Wurzburg Gestapo case-files in StA W.

Besides pointing to a high degree of public co-operation with the Gestapo in enforcing racial/sexual policy, Table 3 also shows that the Gestapo's `own observations', at least when it came to enforcing racial/sexual segregation, were responsible for initiating less than i per cent of such cases, a figure which contrasts sharply with the general figure of i 5 per cent pointed to by Mann in Table 2, and underlines the importance of the Gestapo's reliance on information from external sources. That an additional 15 per cent of all such cases began with information gathered at interrogations, as indicated in Table 3, leads one to suspect that once someone was brought in for interrogation, incriminating information could be wrested from that person. Table 3 shows that various other 'control organizations', such as the SD and Kripo, participated less in enforcing racial policy than in the overall work of the Gestapo. While they helped initiate some 17 per cent of all cases (see Table 2), they contributed to tracking only 5 per cent of all the more specific cases of race transgression. From the Wiirzburg files it looks as though the SD and the Kripo were not nearly as active as is sometimes supposed.

On the other hand, as Table 3 indicates, the role of the Nazi Party and affiliates was greater in enforcing racial policies than in the general functioning of the Gestapo. While they initiated 6 per cent of all cases of the Gestapo, the Party and affiliates initiated 9 per cent of the cases in the Wurzburg files concerning enforcement of racial regulations. The Party was also responsible for an additional 3 per cent which began when it turned up incriminating evidence after being asked to conduct 'political evaluations'. Moreover, on the evidence of local Nazi Party files from several different areas, it would appear that many complaints were handled by the Party on its own and that it passed on only a portion to the Gestapo for 'executive' attentionarrest, interrogation, or imprisonment. Thus, for example, a letter of June 1936 from the Ochsenfurt propaganda office to Wurzburg Party headquarters reported that a hotel- and restaurant-owner dared to put up Jewish persons and to serve them food, even though local Nazis frequented the inn. Since technically nothing illegal had taken place, headquarters was asked what could be done, beyond recommending that the Nazi Party boycott that business."'

Apart from such internal complaints, however, countless private citizens went to local Party headquarters across the country to seek redress. The files from Eisenach in East Germany, for example, reveal a constant flow of complaints. Such documents reveal the NSDAP not merely as a source of information for the Gestapo but, up to a point, as an enforcer on its own. The scattered evidence also suggests that it was as prone to abuse for selfish ends as were the other authorities in Germany"

Paid informers or agents are conspicuous by their absence in Table 3. Perhaps there was enough volunteered information to make the use of agents superfluous. Rarely can it be shown that paid agents offered information about transgressions of racial policy. It may be that the Gestapo had to reserve planted informers of various kinds for the task of cracking the more tightly organized pockets of political resistance, such as those formed by the Com munist and Socialist parties. The absence of documents does not mean that agents were not more involved, but to attempt to say anything further would involve an intolerable amount of guesswork.

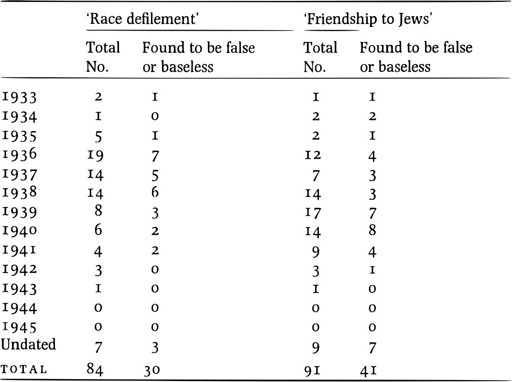

As might be expected, charges alleging 'race defilement' increased dramatically after the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, which specified the crime for the first time (although a number of charges of this type had been laid before those laws were in force: see Table 4). The table also indicates that the greatest number came in 1936; after that there was a gradual decline. The slack was more than taken up, however, by increases in the number of allegations for being 'friendly', sociable, or sympathetic to the Jews, as shown in the table. Indirectly, both sets of figures suggest that such relations were steadily broken off as they were uncovered, or soon disintegrated because of fear of being further denounced.

TABLE 4. Accusations of 'Race Defilement' and 'Friendship to Jews' in the Wurzburg Gestapo Case-Files (1933-1945)

Source: Wurzburg Gestapo case-files in StA W.

2. OPPONENTS OF NAZI ANTI-SEMITISM AND THE FALSELY ACCUSED

Gestapo case-files are records of named individual persons who came to the attention of the Gestapo. Some of these dossiers were created, for example, when the Gestapo had reason to suspect that a person had defied the regime's position on the 'Jewish question'. Not all of these suspicions led to arrests, although some did; others eventually found their way into court, but more were evidently not considered worth pursuing after an initial inquiry. A precise analysis of the percentage of Gestapo investigations which led to arrest, trial, and conviction, like several other important aspects of the history of police practice, is not yet available. Reading through the two collections of case-files which survive, one observes that some of the 'dossiers' are little more than a scrap of information which, after having been brought to police attention, was merely noted without any follow-up, because it was too inconsequential or vague. In every instance, as far as is known, a personal case-file on the suspect was established, alphabetized, and cross-referenced for internal police purposes. The Gestapo (not unlike the rest of the Nazified police) was receptive to all tip-offs, and this was especially so when it came to important 'opponents', such as the Jews, and the policies which were hard to enforce, such as 'race defilement'. On these occasions in particular the Gestapo was anything but fastidious about verifying accusations. An anonymous tip, for example, could lead not only to a demand that a suspect appear at police headquarters, but to an arrest, an extorted confession, and prolonged detention. By virtue of the power to impose 'protective custody' no more than a hint was needed to take someone into custody if a high-profile 'crime' was suspected-and violations of the Nuremberg Laws were of paramount concern. Given all these considerations, it is difficult to accept Sarah Gordon's decision to treat each of the 452 cases of 'race defilement' and 'friendship to Jews' in the Dusseldorf files as evidence of an actual rather than merely alleged 'offence'. If she is unable to defend this decision, it would also be impossible for her to sustain a claim based on this decision, namely that all 452 people were 'opponents' of Nazi anti-Semitism.12

Her subsequent

categorization of these 'opponents' (as 'high', 'middle', or 'low') would then be invalid as well.'

3

The files of the Dusseldorf Gestapo are not qualitatively different from those in Wiirzburg; thus, a careful reading of the dossiers in Wiirzburg should shed some light on what one might reasonably expect to find in the Dusseldorf files. In the Wiirzburg dossiers there are 91 cases in which there was some suspicion of 'behaviour friendly to the Jews'; 41 of these must be considered either as patently false or without any foundation (Table 4). With regard to the 84 `race defilement' cases, 30 of the accused individuals must also be regarded as having been charged baselessly. Table 4 also illustrates the dramatic reduction in opportunities for laying charges (false and otherwise) in this area of social life after the emigration and/or deportation of the Jews. Even so, some false accusations continued after there were hardly any Jews left to be very `friendly' with. (It was still possible, of course, to get into trouble by making an incautious remark about official policy.) The point is that on many occasions opposition to Nazi anti-Semitism was not involved.

Elise Pfister, a waitress in Wiirzburg, reported her employer in October 1938 because he allegedly said that Jews were welcome in his establishment so long as the other guests were not bothered. This turned out to be a false accusation-Pfister simply wanted to leave the firm-and the Gestapo concluded the case by saying that information from the woman 'should be treated with caution in the future'."

Leaving a position with a firm to better oneself without having to pay a penalty could be facilitated in this way, as other cases at the time also make clear.'

7

In October 1939 a forty-one-year-old Wurzburg landlady, Amalie Zettel, was denounced as a `friend to the Jews' by one of her tenants. While Zettel had purchased her house from an earlier Jewish owner, the transaction had been conducted according to the `Aryanization' procedures, as investigation revealed. It was just such a denunciation that Goring had said should be stopped, and the Gestapo concluded its report on the matter as follows: `The denouncer, Franzl Stock, is, according to reliable information, a tenant who, because of his anti-social behaviour in relation to the inhabitants of the house, has repeatedly given cause for complaints. After he had to be asked repeatedly for his monthly rent, he himself decided to lodge the allegation

about the house-owner.' There was no basis whatsoever to Stock's charges, and Zettel in turn opened proceedings against him.

"