The Ghost in My Brain (21 page)

Read The Ghost in My Brain Online

Authors: Clark Elliott

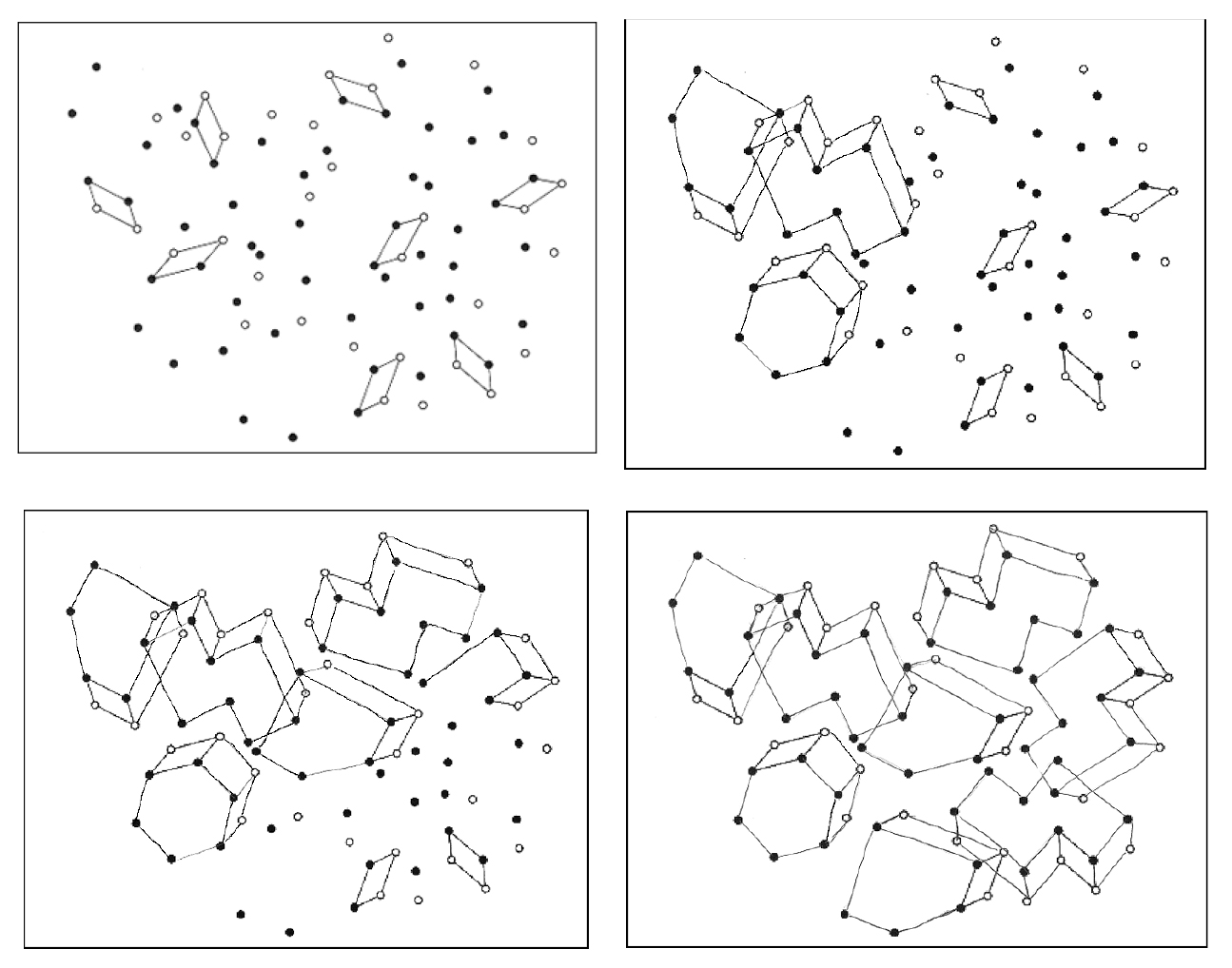

Figure 8:

3D Page of Dots Overlaid

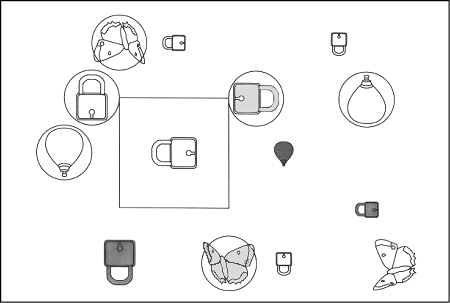

Figure 9:

Snippet of Butterflies Locks Balloons Rules

In the early exercises I was given explicit instructions. After a while I graduated to working out my own rules

based on what was implied in an example, and then following those rules to put the objects into correct sets.

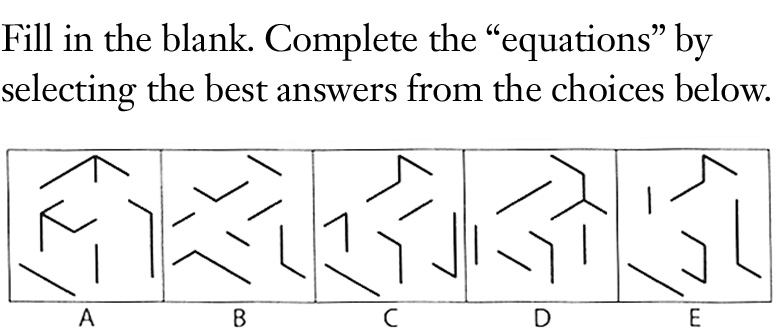

Figure 10:

Geometric Figure Equations

I also worked on making perfect copies of many 8.5 Ã 11 abstract line-drawn schematic pictures that contained parallel line segments, diagonals, circles, triangles, such as the one in

Figure 3

, and many other types of puzzles.

A difficult kind of geometry puzzle involved creating equations by adding and subtracting one figure from another (see

Figure 10

, above). These equations ultimately got very complex, with multiple operands.

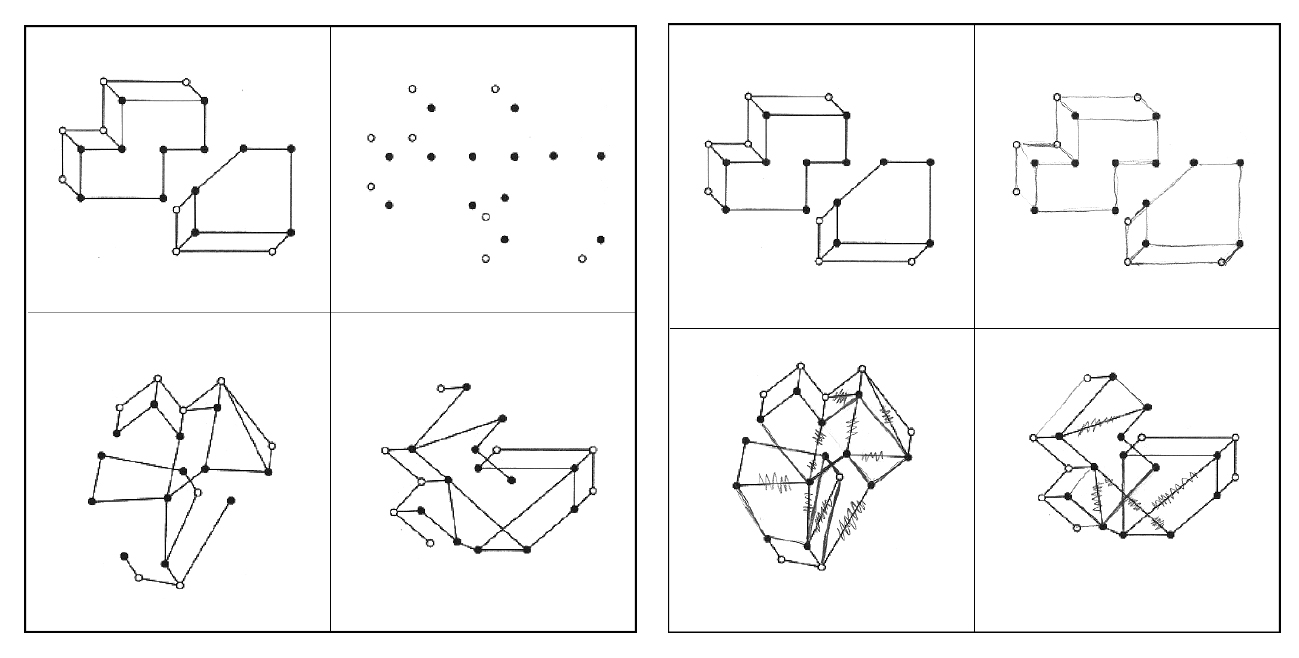

Sometimes I was given overlapping shapes where I had to remove errors by crossing out lines that connected the dots incorrectly (see

Figure 11

).

In all cases the exercises were hierarchical and methodical, were designed to address very specific weaknesses, and were used to bring my symbolic cognitive functioning within normal limits for various kinds of basic cognitive skill categoriesâthat is, importantly,

normal for a very high-functioning intellect.

Figure 11:

Shapes with Lines in the Wrong Places

When I was working on the intense 2D and 3D mental projections like those in

Figure 7

and

Figure 8

, Donalee wanted me to draw out the shapes, with pencil, as soon

as I found them among the cloud of dots. But in keeping with the way I had always studied, I did more than was asked of me. I wanted to get better as fast as possible, and I felt that the harder I worked on these exercises, the sooner I would get back to being myself. So instead of using a pencil, I did the whole of each exercise in my head. I would visualize each of the objects in my mind's eye, and then, keeping that object “alive” (so that I wouldn't accidentally reuse its dots for another shape), I moved on to the next object. In this way I would work through a whole page, often containing fifteen 2D or 3D figures, many of them overlaying one another. At the end I would be able to simultaneously see

all

of the objects rising out of the sea of seventy or more dots as I repeatedly moved from one shape to another in my mind's eye. This gave my eye-aiming systems and cognitive filters lots of guided exercise as I had to repeatedly return to each object to “refresh” the image of it in my mind.

*

Working through a single page of dots the first time might take me forty-five minutes of intense concentration. Because I hadn't actually drawn on the paperâvisualizing all the shapes only in my headâI was able to repeat the exercises many times each week. I would then note the number and types of the objects in a coded sequence on the bottom of the page, to later go over with Donalee.

I also took to working through the exercises in a different variation wherein I practiced

as though I were physically drawing the lines

, but without actually picking up a pencil to do so. That is, rather than simply staring at the page waiting for the shapes to “rise out of” the dots, I imagined I could feel my hand holding a pencil, drawing the objects.

I had always been naturally gifted at these kinds of intense symbolic-geometric visualizations as I worked out many kinds of problems, so this was normal mental exercise for me, and was in keeping with Donalee's belief in matching the exercises to baseline cognitive capabilities. I felt that for

my

brain the intensity of doing the many exercises completely in my head was the only way I could ever hope to restore the levels of reasoning I needed for my work as a professor. At times I would concentrate so hard on the exercises that it was as if I were in another world. It was intensely hard work,

but it felt right.

Yet Donalee was neither mollified nor persuaded. “I need you to actually

write down

your interpretation of the shapes!” she admonished. “I have to check for cognitive deficits in your work, and I need to see how you are drawing your lines. These give me clues about your brain state as you work.

“And look, an important part of the brain's work, as you have seen, is in using cognitive symbols to guide the motor control of your hands, arms, hips, back, and neck muscles. Need

I remind you that you've got a problem there?” She laughed. “We need you to be

physically

translating your inner vision, through your body, into the real world. My exercises are designed to work with these motor skills!”

Despite her objection, we compromised. I would work through the exercises in my own way by visualizing the shapes in my head, and imagining also, in a different version of each exercise, that I was physically drawing them with a pencil. I would do this many times for each exercise, but then, before I returned, I would use a real pencil to actually connect all the dots.

Working through the exercises felt

good

, but despite the great advances I had made, they were still debilitating. After working on themâespecially in the first two monthsâI often could not walk, or do much of anything, so I had to carefully portion out time to work on my homework while leaving enough resources to get through my still-challenging days.

ATTENTION DISORDER AND THE FOLLOWING OF RULES.

“Donalee,” I said at one of my visits two months after I had started with her, “I really don't want to be working on these annoying âfind the rule' exercises anymore. I figured them out right away, weeks ago, and they don't present any challenge to me.”

The exercises were maddening. Donalee was giving me long collections to work through. I had to flip to a page, read the instructions or tease out the rule, and then, using the instructions or the rule, isolate objects that did not match. It was not in my nature to put much effort into such essentially boring, rote work.

Donalee was adamant. “You have to keep working on them,” she replied. “You have a tendency toward attention difficulties.

It runs in your family. In your own case this weaknessâwhich you were able to manage prior to your brain injuryâhas now become problematic. So it's a brain area we've got to strengthen.”

She went on. “In my experience, people with attention difficultiesâespecially high-functioning peopleâalways find reasons why they shouldn't have to follow the rules. Their reasons take many forms, but often are some subset of âthese rules are stupid and it doesn't make any sense to follow them'âa variation on what you are telling me now.

“In fact, these tactics are mostly, unwittingly, used to mask the problem that attention-disordered people

cannot

follow the rules. They can't attend long enough to do so. Life would often be much easier, less chaotic, and more productive, if they could address their cognitive difficulties such that they could

learn to follow rules.

“I'm giving you these exercises so that you can identify the rules, and follow them. Just that. Not only do you have to attend to what the rules are, but you have to form the intention to follow them, and then rehearse, over and over again, the following of those rules. Whether you've figured them out, or agree with them, or they suit you, is irrelevant.”

*

I thought about this and, much to my chagrin, realized that she was right. I came from an intellectually high-functioning, iconoclastic family that generally questioned all rules, and followed them only “when it made sense” to do so. Neither of my parentsâeach of them a graduate of UC Berkeleyâwas good at following rules. My parents would happily expend three times

the energy to avoid following a “stupid” rule as it would have taken to simply “waste” the time following it.

“We need to end as much of the chaos in your life as possible,” Donalee said bluntly. “It is mentally exhausting for you. You will be needing all of your brain resources to lead a normal life.”

Surprisingly, but wonderfully, I found that working through Donalee's puzzles, building solid cognitive capabilities from the ground up, began to translate into real life.

The processes of determining relationships between symbols (such as

part-whole, belongs or doesn't belong, left-to-right ordering, same color/different color

) and of

figuring out the rule, then following it to the letter

were, essentially, the same when manipulating puzzle icons as they were when reasoning about the real world. In both cases the objects and problem-solving procedures got translated into the same internal iconic forms.

Because of all the practice visualizing objects and relationships in the dot puzzles, my ability to generally visualize symbols and relationships from real life gradually got better as well. My ability to figure out the rule in a real-life organizational task, then follow it, got better. My ability to organize visual scenes got better. My ability to balance background context and attentional focus got better. And, the complex 3D puzzles seemed to exercise a very important

spatial

part of my symbolic-reasoning system that I used to solve complex real-world problems.