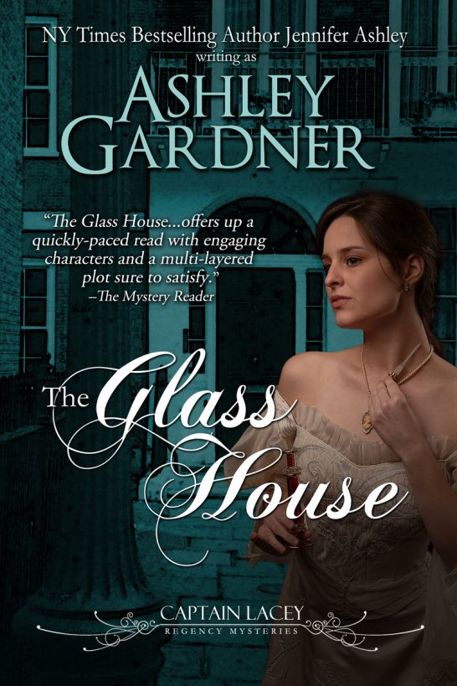

The Glass House

Authors: Ashley Gardner

Tags: #Suspense, #Murder, #Mystery, #England, #london, #Regency, #law courts, #english law, #barristers, #middle temple

The Glass House

by Ashley Gardner

Book 3 of the Captain Lacey Regency Mysteries

The Glass House

Copyright 2005 and 2011 by Jennifer Ashley (Ashley

Gardner)

All rights reserved.

Excerpt from

The Sudbury School Murders

copyright 2011 Jennifer Ashley

Published 2011 by Jennifer Ashley (Ashley

Gardner)

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the author.

This book is a work of fiction. The names,

characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer's

imagination or have been used fictitiously and are not to be

construed as real. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead,

actual events, locales or organizations is entirely

coincidental.

* * * * *

Chapter One

The affair of The Glass House began quietly

enough one evening in late January, 1817. I passed the afternoon

drinking ale at The Rearing Pony, a tavern in Maiden Lane near

Covent Garden, in a common room that was noisy, crowded, and

overheated. Sweating men swapped stories and laughter, and a

barmaid called Anne Tolliver filled glasses and winked at me as she

passed.

I first learned of anything amiss when I left

the tavern to make my way home. It was eight o'clock, the winter

night outside was black and brutally cold, and rain came down. A

hackney waited at a stand, white vapor streaming from the horse's

nostrils while the coachman warmed himself with a nip from a

flask.

I walked as quickly as I could on the slick

cobbles, trying to retain the warmth of ale and fire I’d left

behind in the public house. My rooms in Grimpen Lane would be dark

and lonely, and Bartholomew would not be there.

Since Christmas, Bartholomew, the tall,

blond, Teutonic-looking footman to Lucius Grenville, had become my

makeshift manservant, but tonight he had returned to Grenville's

house to help prepare for a soiree. That soiree would be one of the

finest of the Season, and everyone who was anyone would be

there.

I too had an invitation, and I would attend,

though I much preferred to visit Grenville when he was not playing

host. Grenville was the most sought-after gentleman in society,

being the foremost authority on art, music, horses, ladies, and

every other entertainment embraced by the London

ton

. He was

also vastly wealthy and well-connected, having plenty of peers of

the realm in his ancestry. His manners, his dress, his tastes were

carefully copied. In public, he played his role of man-about-town

to the hilt, employing cool sangfroid and a quizzing glass, one

glance through which could humble the most impudent aristocrat.

I had come to know the man behind the façade,

a gentleman of intelligence and good sense, who was well read and

well traveled and possessed a lively curiosity that matched my own.

People wondered why Grenville had shown interest in me, a half-pay

cavalry officer who had passed his fortieth year. Though I had good

lineage, I had no wealth, no connections, no prospects.

I knew Grenville was kind to me because I

interested him, and I relieved the ennui into which he, one of the

most wealthy men in England often lapsed. He enjoyed hearing tales

of my adventures, and he'd helped me investigate several murders

and mysterious events in the past year.

I could not fault Grenville his generosity,

but I could not repay it either. His charity often grated on my

pride, but in the last year, I had come to regard him as a friend.

If he wished me to attend the crush at his home, I would oblige him

and go, though I would have to endure a night of rude stares at me

and my fading regimentals.

Hence, I enjoyed myself sitting in the

friendly, noisy tavern before I had to venture to Mayfair and face

London's elite.

At least my lodgings had become something

less than dismal since Bartholomew's arrival. Grenville had lent

him to me and paid for his keep, because the lad wanted to train to

be a valet, the pinnacle of the servant class. Therefore, I now had

someone to mix my shaving soap, brush my suits, keep my boots

polished, and talk to me while we chewed through the beefsteak and

boiled potatoes he fetched from the nearby public house.

I suspected Grenville's purpose in sending

Bartholomew to me was twofold--first, because Grenville felt sorry

for me, and second, because he wanted to keep an eye on me. With

Bartholomew reporting to him, Grenville would be certain not to

miss any intriguing situation into which I might land myself.

Bad fortune for him that Grenville had chosen

to call Bartholomew home to help him tonight.

My rooms lay above a bakeshop in the tiny

cul-de-sac of Grimpen Lane, which ran behind Bow Street. The

bakeshop was a jovial place of warm, yeasty breads, coffee, and

banter when it was open. Mrs. Beltan let the rooms above it cheap,

and I'd found her to be a fair landlady. The shop was closed now,

Mrs. Beltan home with her sister, the windows dark and empty.

As I reached to unlock the outer door that

led to the stairs, a voice boomed at me out of the darkness.

"Happily met, Captain."

I recognized the strident tones of Milton

Pomeroy, once my sergeant, now one of the famous Bow Street

Runners. The light from windows in the house opposite shone on his

pale blond hair and battered hat, the dark suit on his broad

shoulders, and his round and healthy face.

In the Thirty-Fifth Light Dragoons during the

Peninsular War, Pomeroy had been my sergeant. In civilian life,

he'd retained his booming sergeant's voice, his brisk sergeant's

attitude, and his utter ruthlessness in pursuit of the enemy. The

enemy now were not the French, but the pickpockets, housebreakers,

murderers, prostitutes, and other denizens of London.

"A piss of an evening," he said jovially.

"Not like the Peninsula, eh?"

Weather in Iberia had been both hot and cold,

but usually dry, and the summers could be fine. Tonight especially,

I longed for those summer days under the sweltering sun. "Indeed,

Sergeant," I said.

"Well, I've not come to jaw about the

weather. I've come to ask you about that little actress what lives

upstairs from you."

I regarded him in surprise. "Miss

Simmons?"

"Aye, that's the one. Seen her about?"

"Not for a week or so."

Marianne Simmons, a blond young woman with a

deceptively childlike face and large blue eyes, eked out a living

playing small parts at Drury Lane theatre. She lived in the rooms

above mine and stretched her meager income by helping herself to my

candles, coal, snuff, and other commodities. I let her, knowing she

might go without otherwise.

Marianne often disappeared for long stretches

at a time. I had once tried to inquire where she went on her

sojourns, but she only fixed me with a cold stare and told me it

was none of my business. I assumed Marianne found a protector

during these absences, temporarily at least. In the past, she'd

always returned within a month, proclaiming her general disgust at

men and asking whether she could share my supper.

"Well, then, sir," Pomeroy went on. "Can you

come along with me and look at a corpse from the river? It might

very well be hers."

I stopped in shock. "What? Good God."

"Pulled out of the Thames not half hour ago

by a waterman," Pomeroy said. "She looked like your actress, so I

thought I'd fetch you to make sure."

My blood went cold. Marianne and I had our

differences, but I certainly didn’t wish so terrible a death on

her. "There's nothing to tell you who she is?"

"Not a thing, so the Thames River gent says.

She's not been dead long. A few hours or more, I should say.

Officer of the Thames River patrol sent for the magistrate, who

sent for me."

So explaining, Pomeroy led me out of Grimpen

Lane and Russel Street and down to the Strand. My walking stick

rang on the cobbles as I strove to match Pomeroy's long stride and

tried to stem my rising worry.

I doubted Marianne would try to do away with

herself; she had a brisk attitude toward life, no matter that it

had not dealt her very high cards. She was not a brilliant actress,

but the gentlemen of her audience liked her bright hair, pointed

face, and round blue eyes.

But accidents happened, and people fell into

the river and drowned all too often. I wondered, if the dead woman

proved to be Marianne, how on earth I would break the news to

Grenville.

We walked east on the Strand and entered

Fleet Street through one of the pedestrian arches of Temple Bar.

The road curved with the river that flowed a few streets away,

though the high buildings hid any aspect of it.

Fleet Street was the haunt of barristers and

journalists, the latter of which were never my favorite sort of

people. We fortunately saw none of them tonight. I supposed they

had retreated to pubs like the one I'd just left, their day's work

finished. Still I kept a wary eye out for one starved-looking

journalist called Billings, who last summer had taken to roasting

me in the newspapers for my involvement in the affair of Colonel

Westin.

We walked all the way down the Fleet to New

Bridge Street, then to Blackfriar's Bridge and a slippery staircase

that led to the shore of the Thames. As we descended away from the

stone houses, the wind took on a new chill.

The river lay cold and vast at the bottom of

the steps, lapping softly at its banks and smelling of rotting

cabbage. Lights roved the middle of the river, barges and small

craft strolling upriver or back down to the ships moored at the

Isle of Dogs or farther east in Blackwall and Gravesend.

A circle of lanterns huddled about ten yards

from the staircase. "Saw her bobbing there," a thin voice was

saying. "Told young John to help me fish her out. Dead as a toad

and all bloated up."

As Pomeroy and I crunched over the shingle

toward them, a man on the gravel bank turned. "Pomeroy."

"Thompson," Pomeroy boomed. "This is Captain

Lacey, the chap I told you about. Captain, Peter Thompson of the

Thames River patrol."

I shook hands with a tall man who had graying

hair and a sunken face, long nose, and thin mouth. He was muffled

in a greatcoat that hung on his bony frame, and his gloves were

frayed. But though his features were cadaverous, his eyes were

strong and clear.

The Thames River patrol skimmed up and down

the river from the City to Greenwich, watching over the great

merchant ships that docked along the waterway. Their watermen

picked up flotsam from the river, either turning it in for reward

or selling it. When they found bodies, they sent for the Thames

River officers, although I suspected that some of the less

scrupulous sold the poor drowned victims to resurrectionists,

unsavory gentlemen who collected bodies to sell to surgeons and

anatomists for dissection.

Thompson asked me, "Pomeroy said the woman

might be an acquaintance of yours."

"Perhaps." I steeled myself for the

possibility. "May I see her?"

"Over here." Thompson pointed a finger in his

shabby glove to the thin gathering of men and lanterns.

I stepped past the waterman who smelled of

mud and unwashed clothes into the circle of light. They had laid

the woman out on a strip of canvas. Her gown, a light pink muslin,

was pasted to her limbs, the sodden cloth outlining her thighs and

curve of waist, her round breasts. Her face was gray, bloated with

water. A wet fall of golden hair, coated with mud, covered the

stones beside her.

She had been small and slim, with a girlish

prettiness. Her hands were tiny in shredded gloves, and her feet

were still laced into beaded slippers. Although her coloring and

build were similar, she was not Marianne Simmons.

I exhaled in some relief. "I do not know her.

She isn’t Miss Simmons."

"Hmph," Pomeroy said. "Thought it was her. Ah

well."

Thompson said nothing, looking neither

disappointed nor elated.

I went down on one knee, supporting my weight

on my walking stick. "She had no reticule, or other bag?"

"Not a thing, Captain," Thompson replied.

"Although a reticule might have been washed down river. No cards,

nothing on her clothes. I imagine she was a courtesan."

I lifted the hem of her skirt and examined

the fabric. "Fine work. This is a lady's dress."

"Might have stolen it," Pomeroy

suggested.

"It fits her too well." I dropped the skirt

and ran my gaze over the gown. "It was made for her."

"Or her lover sent her to a dressmaker,"

Thompson said.

I looked at the young woman’s neck and

wrists, which were bare. "No jewels. If she had a protector, she

would wear the jewels he bought her."