The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (76 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

And finally there was morale to be considered. Early in the month rumors of the Declaration of Independence seeped into the army. There was no large-scale jubilation, but when official word came to headquarters

____________________

10 | Ward, I, 196-201; Freeman, |

11 | GW Writings |

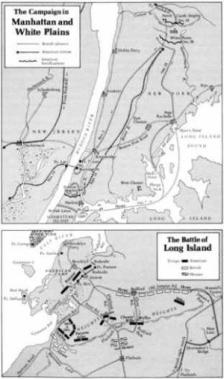

on July 9, Washington ordered the troops mustered and had the Declaration read aloud. In the next few weeks he himself issued orders -- exhortations in everything but name -- reminding his men of the great cause. they were engaged in, the defense of the blessings of liberty. Not only did American rights ride on the performance of the army, but so did the natural rights of man. Near the end of August, Washington had occasion to repeat with even greater passion these calls for patriotic action. For at dawn on the 22nd, Howe began to transport a large force from Staten Island to Gravesend Bay, Long Island. Clinton and Cornwallis led the first of these troops, light infantry, grenadiers, and Colonel Carl von Donop's corps of Hessians. Four frigates covered the landing, and flatboats, bateaux, and galleys carried the soldiers to the bay. By mid-day Howe had put 15,600 men ashore, supported by forty fieldpieces; and on August 25, he sent in General Philip von Heister, a veteran of the Seven Years War, with two brigades of Hessian grenadiers.

12

Washington at first underestimated the size of the enemy's force on Long Island. Nor was he certain of Howe's intentions, believing for two or three days following the landing that nothing more than a feint to draw off his troops from New York City was intended. Once he, Washington, committed himself to Long island, Howe might slip in by water and take a city stripped of defenders. These concerns are understandable but may seem hard to reconcile with Washington's purposes on Long Island and his sense of how New York City should be defended. He had decided to fortify Brooklyn Heights because he recognized that it commanded the southern tip of Manhattan just as the Dorchester Heights had commanded Boston. Hence he felt compelled to divide his army even though General Howe controlled the water and might use this control to keep the Americans separated on the two islands. Washington's problem was almost unsolvable, given his lack of naval strength.

13

To hold Brooklyn Heights, he dug in around Brooklyn Village, anchoring his right on the southwest at Gowanus Creek in salt marshes and swinging his line to the north to Wallabout Bay, where salt marshes gave protection. Out from this line about a mile stretched the Heights

____________________

12 | Freeman, |

13 | Ward, I, 213-14. My account of the Battle of Brooklyn, including the preliminaries discussed here and in the following paragraphs, owes much to Ward's thorough treatment and perhaps even more to Freeman's account. Washington letters in |

of Guan, a range of hills from 100 to 150 feet in height, covered by heavy brush and woods. The side away from Brooklyn, the south side, rose abtuptly to a height of eighty feet in places and was thought to be impassable by troops in formation because of the rise and the dense woods. The woods would also prevent horse-drawn artillery from being moved up into the hills. Four passes breached the Heights of Guan -the coastal pass near Gowanus on the American right, Flatbush about a mile to the east, Bedford Pass another mile farther to the east, and Jamaica Pass almost three miles beyond.

Washington's knowledge of this terrain probably was not detailed, but he had grasped its tactical possibilities before the British landed. The decision to defend the Heights of Guan made sense presumably because Howe would have to string his army out on a line to counter the Americans, thereby reducing the importance of his overwhelming numbers. Should he be allowed to concentrate his forces against Brooklyn Heights, he would inevitably overrun the smaller American army. But if Washington's tactics were intelligent, his dispositions of his troops were not, for he failed to secure his left flank. To some extent, perhaps, General Sullivan was at fault here; the center and left -- Flatbush, Bedford, and Jamaica passes -- were his responsibility, and he left Jamaica, on the eastern end of the line, undefended except for a guard of five men.

The day after Howe's landing, Washington in unhappy ignorance of the state of American troops on Long Island sent over six more regiments and issued an order, amounting to a principled appeal, calling on his soldiers to "acquit yourselves like men." Though most of Washington's exhortation resorted to the "cause" -- "the hour is fast approaching, on which the Honor and Success of this army, and the safety of our bleeding Country depend" -- it contained equal portions of threats, invocations of recent history, and instructions on how to behave under fire: "Remember officers and soldiers, that you are Freemen, fighting for the blessings of Liberty -- that Slavery will be your portion, and that of your posterity, if you do not acquit yourselves like men: Remember how your Courage and Spirit have been despised, and traduced by your cruel invaders; though they have found by dear experience at Boston, Charlestown [a reference to Bunker Hill] and other places, what a few brave men contending for their own land, and in the best of causes can do, against base hirelings and mercenaries."

14

____________________

14 | GW Writings |

The "base hirelings and mercenaries" were the Hessians, of course. The general had ideas about how his soldiers should deal with them -and their British employers: "Be cool, but determined; do not fire at a distance, but wait for orders from your officers." Washington so doubted the courage of his troops that he ordered that men who attempted to "skulk" or "lay down," or who "retreated without Orders" should be instantly shot down. He was hopeful that "no such Scoundrel will be found in this army; but on the contrary, every one for himself resolving to conquer, or die, and trusting to the smiles of heaven upon so just a cause, will behave with Bravery and Resolution: Those who are distinguished for their Gallantry, and good Conduct, may depend upon being honorably noticed, and suitably rewarded: And if this Army will but emulate and imitate their brave Countrymen, in other parts of America, he has no doubt they will, by a glorious Victory, save their Country, and acquire to themselves immortal Honor."

15

The mention of Charlestown, or Bunker Hill, and Boston was shrewd, calculated to conjure up visions of redcoats first tumbled in bloody piles and then sailing out of the harbor with defeat rusting their mouths. Washington himself could never resist an appeal for gallantry in battle nor what inevitably followed it -- "immortal Honor" -- and set this standard for his troops, though doubtless with few expectations.

16

Howe probably contented himself with less fervent demands on his troops. We know that he did not ordinarily talk about the "cause"; he was not altogether sure whether he was engaged in anything nearly so grand as a cause. He sometimes praised his troops' bravery to their faces, and then urged them to look to their bayonets for the real work, a thoroughly professional recommendation. Now on Long Island he did what he often did so well -- nothing. Nothing on the day after the landing, nor on the next day, the 24th, nor on the 25th.

17

Late on August 26, he at last moved. With Clinton in the van with dragoons and light infantry, Cornwallis in reserve with grenadiers, two regiments of foot and artillery, and Percy and himself with the main body, Howe set his army moving by back roads to Jamaica Pass. Clinton reached it by three in the morning, seized the five startled Americans, and the British poured through. By daybreak the British were on the Bedford Road headed west behind the American lines on the Heights

____________________

15 | Ibid., |

16 | Washington's appeals to his troops throughout the war, however, do not reflect disillusionment. |

17 | Diary of Fredefick Mackenzie |

of Guan. They marched quietly and carefully, sawing rather than chopping down trees where they had to widen the road so that wagons and fieldpieces might be drawn along. Sawing would make less noise they thought, and they did not want to be discovered until the American army had been trapped.

18

They need not have worried. About the time Clinton reached Jamaica Pass, General James Grant created a diversion at the other end of the line, the American right, by sending troops up the Gowanus Road. Smallscale skirmishing began sometime around three in the morning, and William Alexander, "Lord" Stirling, the American commander at this part of the defenses, began to prepare for a major attack. At the center of the line Heister's Hessian gunners shelled Flatbush Pass about the same time in order to bold Sullivan, who commanded the American troops there and at Bedford Pass, in place. All this worked beautifully. By nine in the morning Howe's forces had reached Bedford Village and announced themselves with heavy fire. This signal sent Heister's jaegers through Bedford Pass and over the ridge. Sullivan's outposts collapsed almost immediately, and within the hour his army had been overrun from the flank and front.

Stirling's troops on the right -- principally William Smallwood's Marylanders and Colonel John Haslet's Delaware Continentals, raw and untried as they were -- fought bravely. They had never fought anyone before; they could not have learned much about the terrain on Long Island, having been boated over only the day before, but they stood and slugged it out for two hours. Soon they were joined by Pennsylvanians and by Yankees from Connecticut. Stirling did not deploy them behind trees and rocks, but stood them up in the open and had them fight European fashion. By late morning they were almost surrounded. Stirling then sent most of his command across the Gowanus Creek, through the "impassable" marshes into Brooklyn. To cover the rear he held a part of Smallwood's Maryland regiment in place and stayed with these soldiers himself. Just before noon, with Cornwallis now at his rear and on his left flank, Stirling with the Marylanders, 250 strong, attacked, assaulting Cornwallis's grenadiers six times until he and his force were finally broken by overwhelming British fire. By noon on August 27 it was all over. Howe had cleared the Heights of Guan and pressed Washington's shattered command back into Brooklyn Village.

Howe did not exploit his advantage, despite the eagerness of his soldiers

____________________

18 | Ward, I, 216-30, for this paragraph and the three following. |