Read The Good Girls Revolt Online

Authors: Lynn Povich

Tags: #Gender Studies, #Political Ideologies, #Social Science, #Civil Rights, #Sociology, #General, #Discrimination & Race Relations, #Conservatism & Liberalism, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Political Science, #Women's Studies, #Journalism, #Media Studies

The Good Girls Revolt (15 page)

In July, Lester Bernstein promised to come up with some suggestions for better recruitment but when we met again in September, he said that after talking it over with some of his colleagues, he had thought better of it. At the same meeting, executive editor Bob Christopher said that if

Newsweek

were forced by law to set up a recruitment program, the editors would simply make up a list of resources and then ignore it. Kermit Lansner, clearly exasperated with the whole process, insisted that

Newsweek

didn’t need to change its recruitment policies. “Writers come to the magazine over the transom,” he said, “and women aren’t coming. We can’t do anything if they’re not interested.” We told him to go out and look for them. Then, for a good ten minutes, he lamented that actually nobody wanted to come to write for

Newsweek

anymore. In the end, management never gave us an explanation of what efforts, if any, they had made to find a woman for the last five writing slots filled by men.

We did have some success getting women into the reporting ranks. After a summer internship in Chicago, Lala Coleman became a correspondent in San Francisco in the fall of 1970. Sunde Smith was promoted from Business researcher to reporter in the Atlanta bureau and Mary Alice Kellogg went to the Boston bureau. Ruth Ross, an experienced black reporter who had left

Newsweek

to start

Essence

magazine, returned to the New York bureau in 1971. We also got our first female foreign bureau chief when Jane Whitmore, a reporter in Washington, was given that position in Rome in 1971. Management also started hiring men as researchers and finally, after ten years as head researcher in the Foreign department, assistant editor Fay Willey was promoted to associate editor.

But there were casualties. When Trish Reilly, one of the most talented young women on staff, was sent to the Atlanta bureau for a summer internship in 1970, the move terrified her. “I was such a depressive, anxiety case,” she recalled. “I was horrified at the thought of being shipped off someplace but I couldn’t say anything because the women were being set free.” The most helpful person was the bureau’s Girl Friday, Eleanor Roeloffs Clift. Eleanor, whose parents ran a deli in Queens, New York, had dropped out of college and gotten a job at

Newsweek

in 1963 as a secretary to the Nation editor. She was later promoted to researcher and transferred to Atlanta in 1965, when her husband found work there. “Eleanor was the office manager but she ran the bureau,” said Trish. “She gave out the assignments, she did everything, including some reporting.” Indeed, when some of the New York women called Eleanor to say she should stop doing reporting until the editors gave her a raise and a promotion, Eleanor refused and continued her dual roles.

One night Trish was in Birmingham, Alabama, covering a school desegregation story. “I was staying in a crummy Holiday Inn all alone with the Coke machine running outside my door,” she recalled. “I thought, ‘If I have to do this the rest of my life, I will slit my wrist.’ To another woman this would have been a shining moment—covering desegregation in Birmingham! But it totally threatened who I was, being given this adult responsibility, and I was miserable and I couldn’t tell anyone.”

Trish returned to New York after the summer and was offered a permanent spot as a reporter in the Los Angeles bureau. This sent her into a tailspin. “It was announced that I was going to LA and I couldn’t face it,” she remembered. “I told Rod [Gander] I couldn’t go. I knew if you turned down a promotion it was the end of your career, but that was fine. I just wanted to be a researcher.” The only person she confided in was Ray Sokolov, a close friend. Ray told her the editors were bewildered by the fact that Trish had turned down the offer, and they didn’t like it. “Apparently the editors were surprised that a lot of women hadn’t come forward to be reporters and writers,” she later said. “But I understood that because I was one of those women. The women’s movement helped me accept the fact that women were equal to men as intellectuals, but it didn’t change who I was inside. A lot of women were prepared socially and emotionally for it, but for those of us who were traditional women, you couldn’t switch off overnight just because we won a lawsuit.” In fact, Trish thought many of us were too abrasive and too ambitious. “I just didn’t think girls should behave like that—take a man’s job,” she later said. “I found it a little improper.”

Little did she know that some of us “ambitious” types were as conflicted about pushing ourselves forward as she was. I constantly struggled with confidence issues. In 1970, Shew Hagerty, who had promoted me, moved to another department and the new editor was my old boss, Joel Blocker. Since working for Blocker as a secretary in the Paris bureau, I had been writing for nearly a year in New York. But Blocker still saw me as a secretary and told me quite clearly that I would have to prove to him that I could write. Week after week over the next eighteen months, nearly every story I handed in was heavily edited or rewritten. I was so miserable I started looking for another job and thought about leaving journalism. Though I didn’t think the lawsuit was the reason he was punishing me, it didn’t help. I was barely holding on to my job.

By the fall of 1971, a year after the editors committed to “actively seek” women writers,

Newsweek

had hired three women—Barbara Bright, Susan Braudy, and Ann Scott, a researcher at

Fortune

—and nine men. Three

Newsweek

staffers, Pat Lynden, Mary Pleshette, and Barbara Davidson, a Business researcher, had failed their writing tests. The women’s panel was fed up. In October, we reported our frustrations to our colleagues. Furious at management’s intransigence, we once again decided to hire a lawyer. Since Eleanor Holmes Norton could no longer represent us, we were directed to a new clinic on employment rights law at Columbia Law School. One of the teachers was twenty-seven-year-old Harriet Rabb, who agreed to represent us.

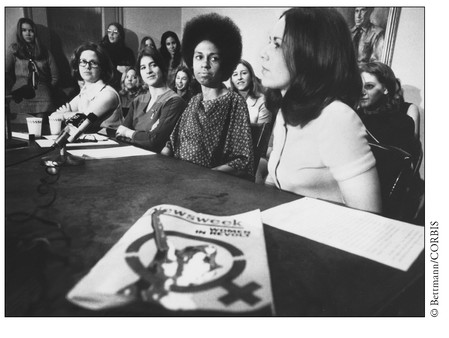

Good girls revolt:

When

Newsweek

published a cover on the new women’s movement on March 16, 1970 (above), forty-six staffers announced we were suing the magazine for sex discrimination (seated from left: Pat Lynden, Mary Pleshette, our lawyer, Eleanor Holmes Norton, and Lucy Howard. I am standing in the back, to the left of Eleanor Holmes Norton).

The Ring Leaders:

When Judy Gingold (top left, in1969) learned that the all-female research department was illegal, she enlisted her friends Margaret Montagno (top right) and Lucy Howard (bottom, with Peter Goldman in 1968) to file a legal complaint.

On the job:

Reporter Pat Lynden had written cover stories for other major publications (with writer David Alpern in 1966).

Covering fashion:

I was the only woman writer at the time of the suit (with designer Halston and Liza Minnelli in 1972).

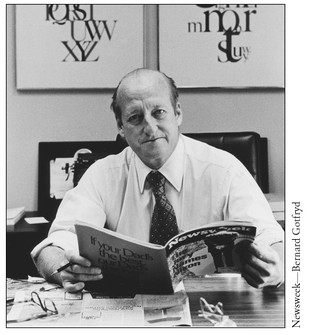

The “Hot Book:”

Editor-in-chief Osborn Elliott transformed

Newsweek

in the Sixties. He called the gender divide a “tradition,” but became a convert to our cause (1974).

When

Newsweek

owner Katharine Graham (with husband, Philip Graham, in 1962) heard about our lawsuit, she asked, “Which side am I supposed to be on?”