The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest

Read The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Timothy Egan’s

T

HE

G

OOD

R

AIN

T

he secret of life in the Northwest runs in packs of silver; as with most mysteries, it lies just below the surface, evident to anyone who thinks it important enough to look. At Willamette Falls, this secret reveals itself in rare flashes amidst the industrial clutter of Oregon City. The river here is a beast of burden, powering the street lights of nearby Portland, grinding wood pulp to paper, settling into locks that lift ships on their way. Against this metallic frenzy a few chinook salmon hurry upstream, driven by a singular impulse to pass on the baton of life and then die. To the continued befuddlement of biologists, they return to the neighborhood of their youth after seeing the world. In the fall, as the ground goes cold and the fields die, they bring a dose of fertility in from the sea, carrying the collected natural history of the Willamette in their gene pool. Fornication, in the ritualized style of the Pacific salmon, is never more charitable—or fatal.

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, DECEMBER 1991

Copyright © 1990 by Timothy Egan

Maps copyright © 1990 by George Colbert

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1990.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Egan, Timothy.

The good rain : across time and terrain in the Pacific

Northwest / Timothy Egan.—1st Vintage departures ed.

p. cm.—(Vintage departures)

Originally published: New York : Knopf, 1990.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79471-0

1. Northwest, Pacific—Description and travel. 2. Northwest,

Pacific—History. 3. Landscape—Northwest, Pacific.

I. Title.

[F851.E28 1991]

979.5—dc20 91-50028

Author photograph by Joni Balter

v3.1

To my mother

,

who always said, Stay West

,

and then showed me why

The flora and fauna grew or died, flourished or failed, in complete disregard for man and his aims. A Man Can Make His Mark, did they tell me? Lies, lies. Before God I tell you: a man might struggle and labor his livelong life and make no mark! None! No permanent mark at all! I say it is true.

KEN KESEY

,

Sometimes a Great Notion

Contents

Introduction

Finishing Up With Grandpa

Chapter One

The Continental Heave

Chapter Three

Toe of the Empire

Chapter Seven

Friends of the Hide

Chapter Eight

Under the Volcano

Chapter Twelve

God’s Country Cancer

Acknowledgments

Writing may be a solitary pursuit, but building a book is collaborative. Support, both inspirational and informational, came from Joni Balter, Wallace Turner and Joel Connelly in Seattle. Through their writings, Bruce Brown, Bill Dwyer, Murray Morgan, Emmett Watson and the late William O. Douglas helped to point me in the right direction. I’m grateful to Carol Mann in New York for her superb job of editorial matchmaking. I would also like to thank my editors at the

New York Times

, particularly Soma Golden and Jon Landman, for allowing me the time to try and get it right. Finally, I owe my biggest debt to Ash Green at Knopf.

T.E.

Introduction

F

INISHING

U

P

W

ITH

G

RANDPA

A

ll summer long Grandpa remains in the basement, two pounds of cremated ash in a plain cardboard cylinder. I can’t get used to the idea of this odorless beige powder as the guy who taught me how to land brook trout with a hand-tied fly, the son of a Montana mineral chaser, the teller of campfire tales about hiding from the Jesuits with his schoolboy chum, a jug-eared kid named Bing Crosby. He had smoked himself to death, and near the end Grandpa couldn’t even take a pee without falling down and gasping for breath. He’d be lying on the bathroom floor of his house in Seattle, a plastic-tipped cigar clenched between his teeth, all that loose skin draped over a shrinking body. Fifty years of two packs a day, that’s what did it. Finally, the emphysema literally asphyxiated him. He was as old as the twentieth century when he died.

My job is to bury him. Something appropriate, my Granny

says, handing me the cylinder after the funeral. “Just throw him off the ferry or dump him into the Yakima River,” she says. “Whatever you think is best.”

This sends me to the map. He’d fished every stream of substance on both sides of the Cascade Mountains, and when the Winnebagos and ghetto blasters began to invade the trout haunts close to home, he went north to British Columbia in search of the adrenal surge that came every time a foot-long native cutthroat rose from the glacial chill to snap one of his tricolored nymphs. With his hip-waders, history books and flasks of Murphy’s, he wandered from the crest of the Canadian Rockies to the mean edge of the Pacific, following fish. As I think about what to do with him now, a river seems a logical last home. Like the chinook salmon that swim eight thousand miles from the Siberian shore to mate and then die in the same Cascade Mountain stream in which they were born, he needs to return, full cycle. But where, exactly?

Stumped for the time being, I set Grandpa on a stool in the basement of this tired house we are renting near Lake Washington. Joni and I live upstairs, but we have to pass through the basement in order to get outside. This means the what-to-do-with-Grandpa question is at least a twice-a-day nuisance. As the summer dries out and the pink glow off the western glaciers of Mount Baker disappears earlier and earlier, I begin to feel like a spiritual delinquent, holding up a long-planned reunion of body and soul.

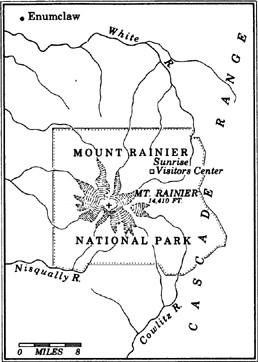

Mid-fall now, the leaves of the red maple out front are clinging to a thread of memory, and we know he has to go. A winter with Gramps in the basement will not do. On a Sunday in late October, one of those weekends when the jet stream is lacerating southeast Alaska but leaving this corner of continental America alone, we put Grandpa in the car and drive south, heading for Mount Rainier. I decide to take him to the apex of the Northwest, the blue hulk which has shadowed over both of us for so long. The volcano of Rainier, I conclude, is where he belongs.

The road follows the water, beginning in Seattle, where Lake Washington is fed by the Cedar River, a point which used to be the favorite summer camp for the salmon-fat Duwamish Indians. Now, it’s covered with Boeing barns stuffed with generic-green 737s and 757s. In his time, Grandpa could still fish the Cedar as it snaked toward the lake; he could take a ferry for a Sunday picnic in the park of Mercer Island; he could climb up the hills just east of the lake, the first swelling of the Cascades, and maybe see a cougar, or at least a few elk among the stands of hemlock and spruce. It’s all highway and cul-de-sac now: the Cedar River straightened

in parts by those orthodontists of nature, the Army Corps of Engineers; Mercer Island cut by ribbons of the most expensive freeway ever built and bridged by two of the world’s longest floating spans; and the hills shaved and shorn of their five-hundred-year-old trees to make way for the waves of California exiles seeking a slice of paradise in a metropolis where insider-trading is not yet required in order to afford a first mortgage.

We follow the Cedar for twenty miles or more, until Rainier comes into sudden view, rising nearly three vertical miles above the dairy farms of Enumclaw. Here the valley is wide and oddly level, as if the Corps has been here earlier, correcting some quirk of nature which didn’t match an Army engineer’s blueprint. The flat valley is Rainier’s own doing, the result of the largest mudflow ever known, a slide which eventually took with it the top two thousand feet of the mountain and spread a swath of broken basalt and clay for forty-five miles down the valley.

Past Enumclaw the road begins to climb, winding through fresh-shaved forest land, denuded in the modern style of the timber industry, and then picks up along the milky way of the White River. “Glacial piss” is what some fishermen call the White River—colder than a football trainer’s icepack, the color of thin milk. Into this river Grandpa will go, or pass through; its source, like most of the water in these parts, is high up on Rainier, locked in another molecular form.

An hour’s drive from Seattle we enter the national park, nearly 250 square miles of protected scenery, thanks in large part to those twin demons of turn-of-the-century timber barons, Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir. Roosevelt helped stir up populist sentiment, thundering against land-grabbers and tree-shavers; in turn, they named an elk after him. The prolific Muir, a naturalist who could massage a phrase as very few scientists can, provided the push from the pen. Muir’s name is attached to the 10,000-foot-high camp on the most popular climbing route to Rainier’s 14,410-foot summit. On summer weekends, Camp Muir is not unlike a small mining town on a roll, full of climbers laden with gear and seeking glory in higher ground. Old Man Muir, dragging around a beard that went past his navel, had a sense of humor not always evident among some of his modern-day followers. But he would most likely disapprove of the odd distinction the camp named after him has gained: it is the site of the world’s most expensive outhouse, a $50,000 solar shitter which uses high-altitude ultraviolet rays to cook and compost climbers’ waste.