The Grand Alliance (130 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

The Grand Alliance

781

7. Please say what you are doing and how you

propose to overcome the growing difficulties of sending

reinforcements into Singapore. Also what has been

done about reducing number of useless mouths in

Singapore Island? What was the reply about supplies?

It is not possible to pursue the story to its conclusion in this volume. The tragedy of Singapore must presently unfold itself. Suffice it here to say that during the rest of the month the Indian Division fought a series of delaying actions against the enemy’s main thrust down the west coast of the peninsula. On December 17 the enemy invaded Penang, where, despite demolitions, a considerable number of small craft were seized intact. These later enabled him to mount repeated flank attacks made by small amphibious forces.

By the end of the month our troops, several times heavily engaged, were in action near Ipoh, a full hundred and fifty miles from the position they had first held, and by then the Japanese had landed on the peninsula at least three full divisions, including their Imperial Guard. In the air too the enemy had greatly increased his superiority. The quality of his aircraft, which he had speedily deployed on captured airfields, had exceeded all expectations. We had been thrown onto the defensive and our losses were severe. On December 16 the northern part of Borneo also was invaded, and soon overrun, but not before we had succeeded in demolishing the immense and valuable oil installations. In all this Dutch submarines took toll of the enemy ships.

The Grand Alliance

782

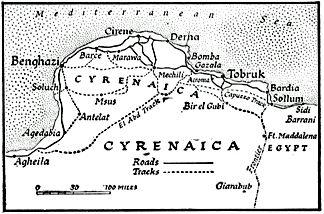

While we sailed the seas General Auchinleck’s battle in the Desert went well. The Axis army, skilfully evading various encircling manoeuvres, made good its retreat to a rearward line running southward from Gazala. On December 13 the attack on this position was launched by the Eighth Army.

This now comprises the 7th Armoured Division, with the 4th Armoured Brigade and support group, the 4th British Indian Division, the Guards Brigade (motorised), the 5th New Zealand Brigade, the Polish Brigade Group, and the 32d Army Tank Brigade. All these troops passed under the command of the XIIIth Corps Headquarters. The XXXth Corps had to deal with the enemy garrisons cut off and abandoned at Sollum, Halfaya, and Bardia, which were fighting stubbornly. The enemy fought well at Gazala, but their desert flank was turned by our armour, and Rommel began his withdrawal through Derna to Agedabia and Agheila. They were followed all the way by all the troops we could keep in motion and supplied over these large distances.

The Grand Alliance

783

With the first week in December came a marked increase in the hostile air power. The 1st German Air Corps was withdrawn from the Russian theatre and arrived in the Mediterranean. The German records show that their strength rose from 400 (206 serviceable) on November 15

to 637 (339 serviceable) a month later. The bulk went to Sicily to protect the sea route to North Africa, but over the desert dive-bombers, escorted by the highly efficient Me.

109 fighters, began to appear in increasing numbers. The supremacy which the Royal Air Force had gained in the first week of the battle no longer ruled. We shall see later how the revival of the enemy air power in the Mediterranean during December and January and the virtual disappearance for several months of our sea command was to deprive Auchinleck of the fruits of the victory for which he had struggled so hard and waited too long.

The Grand Alliance

784

Everyone in our party worked incessantly while the

Duke of

York

plodded westward, and all our thoughts were focused on the new and vast problems we had to solve. We looked forward with eagerness, but also with some anxiety, to our first direct contact as allies with the President and his political and military advisers. We knew before we left that the outrage of Pearl Harbour had stirred the people of the United States to their depths. The official reports and the press summaries we had received gave the impression that the whole fury of the nation would be turned upon Japan.

We feared lest the true proportion of the war as a whole might not be understood. We were conscious of a serious danger that the United States might pursue the war against Japan in the Pacific and leave us to fight Germany and Italy in Europe, Africa, and in the Middle East.

I have described in a previous chapter the enduring, and up to this point growing, strength of Britain. The first Battle of the Atlantic against the U-boats had turned markedly in our favour. We did not doubt our power to keep open our ocean paths. We felt sure we could defeat Hitler if he tried to invade the Island. We were encouraged by the strength of the Russian resistance. We were unduly hopeful about our Libyan campaign. But all our future plans depended upon a vast flow of American supplies of all kinds, such as were now streaming across the Atlantic. Especially we counted on planes and tanks, as well as on the stupendous American merchant-ship construction. Hitherto, as a non-belligerent, the President had been able and willing to divert large supplies of equipment from the American armed forces, since these were not engaged. This process was bound to be restricted now that the United States was at war with Germany, Italy, and above all Japan. Home needs would surely come first? Already, after Russia had been attacked, we had rightly sacrificed to aid the Soviet armies The Grand Alliance

785

a large portion of the equipment and supplies now at last arriving from our factories. The United States had diverted to Russia even larger quantities of supplies that we otherwise would have received ourselves. We had fully approved of all this on account of the splendid resistance which Russia was offering to the Nazi invader.

It had been none the less hard to delay the equipment of our own forces, and especially to withhold vitally needed weapons from our army fiercely engaged in Libya. We must presume that “America First” would become the dominant principle with our Ally. We feared that there would be a long interval before American forces came into action on a great scale, and that during this period of preparation we should necessarily be greatly straitened. This would happen at a time when we ourselves had to face a new and terrible antagonist in Malaya, the Indian Ocean, Burma, and India.

Evidently the partition of supplies would require profound attention and would be fraught with many difficulties and delicate aspects. Already we had been notified that all the schedules of deliveries under Lend-Lease had been stopped pending readjustment. Happily the output of the British munitions and aircraft factories was now acquiring scope and momentum, and would soon be very large indeed. But a long array of “bottlenecks” and possible denials of key items, which would affect the whole range of our production, loomed before our eyes as the

Duke of York

drove on through the incessant gales. Beaverbrook was, as usual in times of trouble, optimistic. He declared that the resources of the United States had so far not even been scratched; that they were immeasurable, and that once the whole force of the American people was diverted to the struggle results would be achieved far beyond anything that had been projected or imagined. Moreover, he thought the Americans did not yet realise their strength in the The Grand Alliance

786

production field. All the present statistics would be surpassed and swept away by the American effort. There would be enough for all. In this his judgment was right.

All these considerations paled before the main strategic issue. Should we be able to persuade the President and the American Service chiefs that the defeat of Japan would not spell the defeat of Hitler, but that the defeat of Hitler made the finishing-off of Japan merely a matter of time and trouble? Many long hours did we spend revolving this grave issue. The two Chiefs of Staff and General Dill with Hollis and his officers prepared several papers dealing with the whole subject and emphasising the view that the war was all one. As will be seen, these labours and fears both proved needless.

The Grand Alliance

787

14

Proposed Plan and Sequence of the

War

My Three Papers for the President

—

Part I, The

Atlantic Front

—

Hitler’s Failure and Losses in

Russia

—

My Ill-Founded Hopes of General

Auchinleck’s Victory in Cyrenaica

—

Possible

German Thrust Through the Caucasus — Urgent

Need to Win French North Africa

—

British and

American Reinforcements for North Africa

—

Request for American Troops in Northern Ireland

—

Request for American Bomber Squadrons to

Attack Germany from Great Britain

—

Possible

Refusal by Vichy to Co-operate in North Africa

—

The Consequential Anglo-American Campaign of

1942

— Our Relations with General de Gaulle —

The Spanish Problem

—

The Main Objectives of

1942

— Part II, The Pacific Front

—

Japanese

Naval Superiority — Their Resources a Wasting

Factor

—

Our Need to Regain Superiority at Sea

—

British Offer to America of the “Nelson” and the

“Rodney

” —

The Warfare of Aircraft-Carriers

—

Vital Need to Improvise — Danger of Creating Too

Large an American Army

—

My Assertion of the

Need for Large-Scale Operations on the Continent

—

Part III, The Campaign of

1943

— Possible

Situation at the Beginning of

1943

— West and

North Africa in Anglo

-

American Control — Turkey

Effectively in the Allied Front

—

A Footing Gained

in Italy and Sicily— Need to Prepare for Landings

in Western and Southern Europe

—

Major Assault

The Grand Alliance

788

in

1943

— Largely an Amphibious Operation

—

Continuous Preparation by Bombing of Germany

and Italy

—

Hope of Ending the War in

1943

or

1944

— Staff Concurrence with My Views — All

the Objectives Ultimately Achieved

—

A Fortunate

Delay in the Final Assault.

T

HE EIGHT DAYS’ VOYAGE, with its enforced reduction of current business, with no Cabinet meetings to attend or people to receive, enabled me to pass in review the whole war as I saw and felt it in the light of its sudden vast expansion. I recalled Napoleon’s remark about the value of being able to focus objects in the mind for a long time without being tired –

“fixer les objets longtemps sans être

fatigué.”

As usual I tried to do this by setting forth my thought in typescript by dictation. In order to prepare myself for meeting the President and for the American discussions and to make sure that I carried with me the two Chiefs of Staff, Pound and Portal, and General Dill, and that the facts could be checked in good time by General Hollis and the Secretariat, I produced three papers on the future course of the war, as I conceived it should be steered. Each paper took four or five hours, spread over two or three days. As I had the whole picture in my mind it all came forth easily, but very slowly. In fact, it could have been written out two or three times in longhand in the same period. As each document was completed after being checked, I sent it to my professional colleagues as an expression of my personal convictions. They were at the same time preparing papers of their own for the combined Staff conferences. I was glad to find that, although my theme was more general and theirs more technical, there was our usual harmony on principles and values. No differences were expressed which led to argument, and very few of the facts required correction. Thus, though nobody was committed in a The Grand Alliance