Read The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia Online

Authors: Peter Hopkirk

Tags: #Non-fiction, #Travel, ##genre, #Politics, #War, #History

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia (46 page)

In the spring of 1858, Nikolai Khanikov, a Russian agent, crossed the Caspian and reached Herat, from where he intended to proceed secretly to Kabul and make overtures on behalf of his government to Dost Mohammed. As it happened, the Afghan ruler had just concluded an alliance with the British, towards whom he was feeling particularly well disposed since they had ejected the Persians from Afghanistan without so much as setting foot there themselves. He no doubt remembered too the painful consequences for himself, twenty years earlier, of his dallying with Captain Vitkevich, the last Tsarist agent to visit Kabul. And now he had witnessed the defeat of the Russians on the Crimean battlefield by the British and their allies, not to mention the failure of St Petersburg, for the second time in eighteen years, to come to the assistance of its Persian friends. There was little question in Dost Mohammed’s mind as to which of the two rivals was the more powerful, and therefore worth remaining on good terms with. The one thing he most desired, moreover, was Herat, which the Russians were never likely to bestow upon him as this would finish them for ever with the Persians.

Khanikov was sent packing, without even seeing Kabul, despite the wild rumours then circulating in the capital that the British in India had all been slaughtered. Considering also the intense pressure that Dost Mohammed found himself under from the more fanatical of his followers to be allowed to join the uprising against the infidels, the British had good reason to feel profound gratitude towards the ruler they had once removed forcibly from his throne. For at a time when they were fighting for their very survival against the ‘enemy within’, the intervention of the Afghans would have been a stab in the back which would most likely have proved decisive. Dost Mohammed was to receive his reward some years later. In 1863, when he led his troops against Herat, the British raised no objection. They would have preferred the country to remain divided, lest under a less friendly successor to the ageing Dost Mohammed a united Afghanistan should prove a threat to India. As it was, just nine days after his victory, the old warrior died, happy in the knowledge that he had restored order to his kingdom, and regained control over this long-lost province. But what he did not know was that history would repeat itself with uncanny precision, and that within fifteen years Britain and Afghanistan would be at war again. A lot, however, was destined to happen before that.

The suppression of the Mutiny, which had been achieved by the spring of 1858, was to have the most far-reaching consequences for India. It was to lead to a massive shake-up in the way the country was ruled, and to mark the end of the East India Company’s two and a half centuries of sway over 250 million people. At the time of the outbreak, India was still nominally run from the Company’s headquarters in Leadenhall Street in the City of London, albeit with ever-increasing interference from Downing Street and Whitehall as improved communications made this easier. In August 1858, in an attempt to resolve the deep resentments and antagonisms which had led to the Mutiny, the British government passed the India Act, abolishing the powers of the Company and transferring all authority to the Crown. A new Cabinet post – that of Secretary of State for India – was created, and the old Board of Control, together with its powerful President, was abolished. In place of the Board an Advisory Council of fifteen members was appointed, eight of whom were chosen by the Crown and the others, initially, by the Company. At the same time the Governor-General was given the additional title of Viceroy of India, being the personal representative of the Queen.

There were radical changes too in the organisation of India’s armed forces, then forming one of the largest armies in the world. A fresh start was obviously called for to restore the confidence of the sepoys in their officers and vice versa. The higher ranks of the Company’s Army had long been filled with ageing, time-serving officers (of whom General Elphinstone had been merely one), in whose abilities and leadership the troops had little confidence. Worse, during the disastrous retreat from Kabul, many of the officers had deserted their men so as to make their own escape, leaving them to a chilling fate at the hands of the Afghan soldiery. Significantly, those native regiments which had fought in Afghanistan were among the first to join the Mutiny. Now, just as the East India Company ceased to exist, so too did its once formidable army. The regiments, both European and native, were transferred to the newly formed Indian Army, which was under the ultimate authority of the War Office in London. All artillery was henceforth placed under European control.

Altogether the Mutiny had been a close-run thing, and the nightmare experienced by the British during it served only to intensify their paranoia over Russian interference in India’s affairs. Nonetheless, the enemy within had been crushed, and India was to remain relatively quiet for the rest of the century. But beyond the frontiers it was a very different matter. By defeating the Russians in the Crimea, the British had hoped not merely to keep them out of the Near East, but also to halt their expansion into Central Asia. As things turned out, it was to have quite the opposite effect.

THE CLIMACTIC YEARS

‘Whatever be Russia’s designs upon India, whether they be serious and inimical or imaginary and fantastic, I hold that the first duty of English statesmen is to render any hostile intentions futile, to see that our own position is secure, and our frontier impregnable, and so to guard what is without doubt the noblest trophy of British genius, and the most splendid appanage of the Imperial Crown.’

Hon. George Curzon, MP,

Russia in Central Asia,

1889.

Henry Pottinger (1789–1856), who as a subaltern explored the approach routes to India disguised as a horse-dealer and a holy man

Arthur Conolly (1807–42), who first coined the phrase The Great Game’ and who was later beheaded in Bokhara. Seen here in Persian disguise

General Yermolov (1772–1861), conqueror of the Caucasus. His men wept when he was later disgraced

General Paskievich (1782–1856), who replaced Yermolov and continued Russia’s ruthless drive southwards

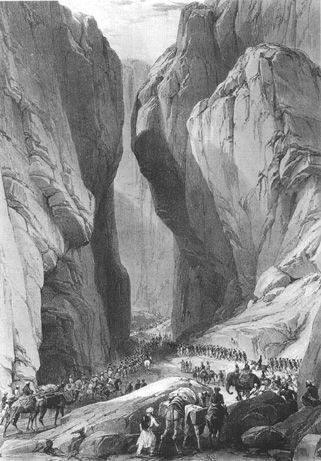

British troops entering the Bolan pass in 1839 on the way to Kabul. The Bolan and Khyber passes, it was feared, could also bring Russian troops into India

The British advance into Afghanistan in 1839. Ghazni, the last enemy stronghold before Kabul, falls after the gates are blown open by Lieutenant Henry Durand