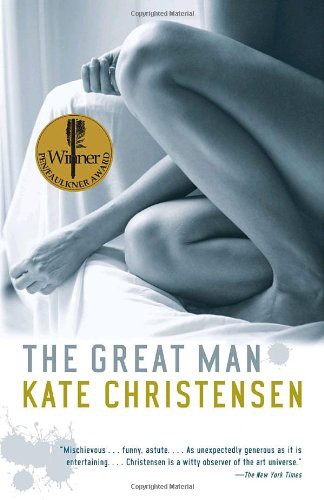

The Great Man

Authors: Kate Christensen

Contents

The New York Times, Thursday, August 9, 2001

The New York Times Book Review, September 16, 2007

For Lizzie

Perhaps being old is having lighted rooms

Inside your head, and people in them, acting

People you know, yet can’t quite name; each looms

Like a deep loss restored, from known doors turning,

Setting down a lamp, smiling from a stair, extracting

A known book from the shelves; or sometimes only

The rooms themselves, chairs and a fire burning,

The blown bush at the window, or the sun’s

Faint friendliness on the wall some lonely

Rain-ceased midsummer evening. That is where they live:

Not here and now, but where all happened once.

—Philip Larkin, “The Old Fools”

THE NEW YORK TIMES, THURSDAY, AUGUST 9, 2001

Influential Figurative Painter Oscar Feldman Dies at 78

By

GINA TSARKIS

Oscar Feldman, whose bold and innovative female nudes are among the most admired and influential artworks of recent years, died of a heart attack August 7 in the Riverside Drive apartment where he’d lived with his wife and son for many decades. He was 78.

Until the end of his life, Mr. Feldman was a dedicated and accomplished artist, and his paintings are often shown in museums and galleries. For decades, he worked every day in his studio on the Bowery. Mr. Feldman was admired both for his prodigious output and the steadfastness of his artistic aims. Throughout his artistic career, his primary, indeed only, subject was the female nude.

“The female body is the ultimate expression of truth and beauty,” he wrote. “I mean truth in all its ramifications: terror included, and death. Beauty likewise: There is a dead stinking creature in every perfect shell on the sand, and in many ways that is the whole point.”

Oscar Avram Feldman was born April 5, 1923, in New York City. The son of an Orthodox Jewish butcher, he grew up on Ludlow Street on the Lower East Side. He attended P.S. 137 and 65, then Seward High School. Mr. Feldman was a Brooklyn College student in the early 1940s, when Jackson Pollock and other artists created the stylistic revolution that came to be known as Abstract Expressionism. After graduating with a degree in art history in 1945, Mr. Feldman briefly attended the Art Students League, but dropped out halfway through his first year to work as a taxi driver and paint on his own. He rented a loft on the Bowery, which he kept as his studio when he married Abigail Rebecca Lebowitz in 1955 and moved to Riverside Drive. Their son and only child, Ethan Saul Feldman, was born in 1959 and was diagnosed with severe autism at the age of three.

Largely self-taught, Mr. Feldman chose deliberately not to follow the Abstract Expressionists’ path, preferring instead to work in the figurative vein that characterized his work until the end of his life. Mr. Feldman expressed admiration for Philip Guston alone of his near contemporaries. Mr. Guston abruptly abandoned abstraction for the cartoonlike, strangely passionate, rough drawings that shocked the art world in the 1960s.

Mr. Feldman’s nudes are characterized by the boldness of his brush strokes and palette. He painted women as complex and earthy, never idealized or purely sexualized. His treatment of skin in particular, or “flesh,” as he liked to call it, was notable for its range of colors and textures. “The flesh, not the eye,” he wrote, “is the portal to the soul.”

“Oscar Feldman’s work was bold and original and gives definition to those two words,” said Earl A. Powell, director of the National Gallery of Art. “His work was exciting, determined, and passionate. He made a huge contribution to postwar art.”

Hilton Kramer, the idiosyncratic and often lacerating art critic and editor of “The New Criterion,” has described Mr. Feldman’s work as “ballsy almost to the point of testicular obnoxiousness, going up to but never crossing that line.”

If not widely known to the general public, his paintings are prized by collectors and are housed in many leading museums, including the National Gallery of Art, the Hirshhorn Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. His full-size paintings routinely sell for more than $1 million.

Mr. Feldman led a life of relative isolation from the rest of the art world by choice. He also disavowed politics and any connection with the antiwar movement. In 1987, when he was honored by the Guggenheim Museum, he came to the reception wearing a guayabera shirt and work trousers spattered with paint. He was a larger-than-life figure, by all accounts opinionated, occasionally boisterous, visceral, with insatiable appetites of many kinds.

In 1976, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and he received a National Medal of Arts from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1986.

“When I think of art, I think of women,” he wrote, riffing on Agnes Martin’s famous lines. “Women are the mystery of life.”

He leaves behind his wife, Abigail, their son, Ethan, and his sister, the well-known abstract painter Maxine Elizabeth Feldman.

One

“It’s amazing how well you can live on very little money,” said Teddy St. Cloud to Henry Burke over her shoulder as she strode into the kitchen of her Brooklyn row house. She hoped he was noticing that her hips and waist were still girlishly slender, her step youthful, and that he’d describe her accurately instead of saying she was “gaunt but chipper,” like that sour-faced squaw with the crooked teeth from

The New Yorker

who’d written the profile of Oscar a few years ago. “I hope you’re a Reform Jew,” she added. “I got prosciutto.”

“I’m not Jewish,” he said after a second of displacement. They stood somewhat awkwardly together in the kitchen, not sure suddenly where to go now that their short walk down the hall had disgorged them into their destination. “But people often think—”

“Burke,” she said. “That’s not the Ellis Islandization of Berkowitz?”

“No,” said Henry. “It’s English.”

She leaned against the counter, her eyes fixed on some middle distance in her mind. She suspected that she looked much older in person than Henry had expected, but then, of course, she was seventy-four, and the person he’d no doubt been expecting, unconsciously, to meet was the young woman Oscar had fallen in love with. But she was proud of the fact that as old as she was, she still resembled her younger self. Her oval, narrow face had aged markedly, with shallow grooves running along both sides of her nose, slight hoods over her eyes, a subtle lengthening of the earlobes, a thinning of the lips, a network of extremely fine wrinkles around her eyes. But she held her small, well-shaped head very high, with the self-aware edge of mischief and manipulation Oscar had loved, eyes glittering foxily, as if she were about to snap out of her feigned concentration and laugh at her observer for being fooled into thinking she hadn’t been watching him all along. This air of expressive, confident intelligence, Oscar had told her, was one of the sexiest qualities about her, the electric flame that ran almost visibly soft and licking over her skin, hinting at interesting flare-ups. Then he had added that having incredible boobs didn’t hurt.

“Please sit down,” said Teddy; she intended it as a command. She wasn’t impressed by Henry. She guessed that he was forty or thereabouts. He looked like a lightweight, the kind of young man you saw everywhere these days, gutless and bland. He wore soft cotton clothing, a little rumpled from the heat and long drive in the car—she would have bet it was a Volvo. She could smell domesticity on him, the technologically up-to-date apartment on the Upper West Side, the ambitious, hard-edged wife—women were the hard ones at that age. Men turned sheepish and eager to please after about forty. Oscar had been the same way; he’d turned into a bit of a hangdog at around forty and hadn’t fully regained his chutzpah until he’d hit fifty or so, but even then, she had never lost interest in him, and she was still interested in him now, even though he was gone.

Henry chose a chair facing her and sat at the table.

“Look at this melon,” she said. “I asked my grocer to give it to me half price by letting him think it was a little soft. Well, it is, but just in one small spot.”

She began slicing the cantaloupe in half on a cutting board, holding the knife in her small square hand. Her kitchen was a long, narrow galley-shaped room with glass-fronted cupboards and an old-fashioned stove and refrigerator, a deep cast-iron sink. The room, like the rest of the house, felt as if she were only temporarily inhabiting it. It had no particular odor. Most old houses were clogged with the olfactory remnants of years of living, the memories of long-ago meals, hidden mold, the strong scent of people. This wasn’t the house she had lived in when she and Oscar were together, but the one she’d bought after his death five years ago, after selling the other one. This one had lost its history when the family who’d owned it for decades had moved out with all their stuff and Teddy had moved in with hers. Somehow, during the transfer, everything had discharged its freight of sediment, the walls of the house, her furniture and belongings, and now it all just smelled clean and impersonal. None of Oscar’s paintings hung on these walls: Oscar had never given her one.

“So,” she said abruptly from the sideboard. “What can I tell you about the great man?”

“Well,” said Henry, caught slightly off guard. “I was thinking we would start at the beginning. For now, just talk about him. We’ll get down to the nitty-gritty of dates and times later. Maybe start with how you met him, how the two of you fell in love—”

“Wine?” she said with a glint of aggression. She reached into the refrigerator, the corkscrew already in her other hand. “It’s a Sancerre, but not as expensive as it tastes, by far.” She wrested the cork from its hole with a faintly savage twist of her wrist. She had been expecting someone Jewish like Oscar, someone ballsy, someone fun to banter and flirt with, not this twerp in rumpled khakis.

“Sure,” he said with a puzzled sidelong look up at her.

“Henry,” she said as she set his glass down with a snap in front of him, “let’s establish one thing right now. This discussion is nonnegotiable. If you won’t listen to what I have to say, you can drink your wine and eat a little melon and then you get up and leave. You’ve clearly arrived with some preconceived notions, and if you can’t shake them loose out of your head like a lot of…moths, then I have nothing to say to you.”

Henry blinked. “I have no preconceived notions,” he said. “I’m here to listen.”

“I want to see a flock of moths rising from your head,” she said. “I’m going to roll the melon with prosciutto now, and when I next turn around, I want to see white fluttery little things rising from your hair and flying out the window.”

She flung open the casement window over the sink and the room was immediately crowded with the sounds of tree leaves, birdsong, and the shouts of kids in a nearby backyard. Her back was turned to him. She could feel her body quivering like an arrow aimed at someone’s heart as she worked.

“You’re right about this wine,” he said. “It’s delicious.”

“No man should ever use the word

delicious,

” she said.

“Teddy,” he said clearly.

She turned slowly to stare at him. Had he actually just called her by her nickname? They looked at each other blank-faced for an instant, and she imagined that he was also wondering this same thing.

“Claire,” they both corrected at once.

“Yes?” she said.

“Talk to me about Oscar,” he said. He took another taste of wine.

“The great man,” said Teddy with a private inner smile, “was the biggest human baby in all of history. That’s no secret: We all know how his women propped him up, me and his wife, Abigail, and sister, Maxine, and our daughters, not to mention every woman he met at an opening or on a train. He couldn’t live without a woman around to look at and probe, by which I mean fuck but also investigate thoroughly.”

Henry picked up his pen and glanced at his notebook but didn’t write anything down.

“He couldn’t live without a woman around,” she repeated. She knew he wanted dates, knew his monomaniacal, orderly biographer’s mind was lying in wait, biding its time, until it could spring forth like an anteater’s tongue and cleanly extract the facts of her history with Oscar like a swath of ants from an anthill. She felt herself resist this with everything she had. No fact, no date—“Oscar Feldman first met Claire St. Cloud on October 7, 1958,” for example—could convey anything of what had really gone on between them. “He saw women as the most powerful beings on earth. You can see it in his portrait of our daughter Ruby as a baby, the girl child with the knowing eyes of a brutal queen. He could catch that complex expression in a baby girl without undercutting her cuteness, without forgetting she was just a baby. But he wasn’t Picasso.”

She looked at him for a reaction. He smiled a little.

“Well, obviously no one is Picasso,” she went on. “That’s not what I meant. My point is, Oscar had no fear of women’s power; he thrived on it. He got off on how strong the women in his life all were; it turned him on; he sucked on the nipples of all of us. That’s where his strength came from. He went right to the source, and it always flowed. His electricity outlets. I think we all liked Oscar, really

liked

him, not only loved him—all of us in our own different ways, even his sister, Maxine, with whom he never got on at all. I think she secretly liked him, too.”

“What’s the difference?” he interjected. “Love, like.”

“I imagine,” she went on as if he hadn’t interrupted, “that Picasso was erotic catnip, with his fear and arrogance and his cold sexual eye. But he didn’t really like women, and I don’t imagine women really liked him, although they may have felt no end of passion for him, the feckless need to conquer or submit. Oscar was needy and soulful, and he liked women without fear. He respected us; he let us be as powerful as we were capable of being. But he wasn’t pussy-whipped, as the excellent expression goes, not by me, not by his wife, not by his mother when she was alive, although he adored her, too. He was fully independent of us. He came and went as he pleased and didn’t let us control him…. No, he was anappreciator. I liked him right back, more than I’ve ever liked anyone else, my own children included.”

She stopped for a moment to think. This time, Henry didn’t interrupt her. “Well, we women don’t always like our children, not always; we love them with that primal mother instinct, and we love our power to take care of them, but sometimes we don’t like them somewhere deep inside. I sometimes felt it toward my twin girls—I couldn’t help it—maybe because I had them both at once, so it was intensified, and of course their father was no help whatsoever; I did it all alone. Which is completely preferable, please don’t misunderstand me. I didn’t want any help from Oscar. This way, I had all the power; I was in control. It was a fair trade-off, I thought. You haven’t written anything down yet.”

“Some women go off the opposite edge,” said Henry. “My wife adores our baby son beyond all reason. I worry sometimes that she’ll eat him alive. This morning, she kissed him with the predatory zeal of a succubus.”

Teddy smiled at him, appreciating the phrase. “We all adore our babies beyond reason; it’s the way we’re made. And I didn’t say I thought

all

women harbor a small amount of dislike for their children; obviously, I couldn’t possibly know that.”

“Abigail Feldman talked at length to me a few days ago about Ethan,” he said. “How it feels to love someone who can’t express love back…She talked about how pure her love for him has always been, untainted by resentment of any kind.”

“That’s love, Henry. You’re not making the distinction. He’s so deeply autistic he’s locked up in his own mind; it’s impossible to dislike someone who isn’t fully there. Dislike requires presence.”

“She was very open with me. You are, too. I appreciate that. I had expected it to be much harder to get you all talking.”

“Then you didn’t know Oscar. He always got us all to spill everything, hold nothing back, so we’re well trained.”

“In that case,” said Henry gingerly but with a daring expression, as if he thought he was about to cross a line, “since the subject has been brought up, Maxine suggested to me that the reason Oscar stayed with you was that he felt displaced. That when Ethan was born, of course all Abigail’s energy and time went to her son. Maxine suggested that Oscar replaced her with you.”

“Did she say that?” asked Teddy, hoping she sounded calm; she’d never liked Oscar’s sister one bit, and knew it had always been mutual. It enraged her that this version of her affair with Oscar might make it into Henry’s book in any form. “I’m not surprised that Maxine would draw such a crude, wrongheaded, idiotic conclusion about why Oscar loved me.”

“It’s understandable that someone might draw such a conclusion…. It seems like elementary psychology, doesn’t it?”

“I was right,” Teddy snapped. “Those moths are eating into your brain. Burrowing into the wet gray folds and gouging tunnels.” She stopped and looked hard at him, something working in her expression. “I bet,” she said, “you’re one of those failed painters who think they can redeem themselves if they pay homage to Saint Oscar. And I bet you’re projecting your own sexual frustration onto Oscar.”

Henry coughed, probably with surprise.

“Here, have some melon,” she said. “Trust me, the prosciutto is some of the best in Brooklyn.”

“You were right about the wine, I’ll give you that,” he said.

“I’m always right,” she said. “It would be much easier for both of us if you just accepted that now and proceeded accordingly. Oscar came to me, in short, because I was exciting. I always liked Abigail, by the way, when I met her at openings and so forth, but I never thought she had much juice. Oscar married her to please his family. He took up with me to please himself.”

“Fair enough,” said Henry.

She imagined he was probably thinking he should appease her, or else he was feeling sorry for her for just being Oscar’s mistress all those years, and never his wife.

“Fair enough,” he repeated.

Nettled, she turned to the window to look out at the pale blue Brooklyn sky, crisscrossed by wires and leaf-filled branches.

“This prosciutto is perfect,” Henry blurted through a mouthful of cantaloupe. “I was going to say ‘delicious,’ but I was afraid you’d stab me.”

“It’s such a precious word,” said Teddy. “No one should use it to refer to anything but food, and even then, with caution. My dearest, oldest friend uses it to describe her grandchildren, the summer morning, a cello sonata on ‘Evening Music,’ and the way her bare feet feel on the sands of Shelter Island. I can’t believe she’s still my friend, but we were college roommates, and then we raised our children together.”

“Lila Scofield,” said Henry, taking another piece of melon.

Teddy laughed. “You are diligent,” she said. She stood there, her hands on her hips, looking at him. She wore a straight ankle-length off-white skirt, a long-sleeved white crew-necked T-shirt, and white sneakers without socks. In these plain and timeless clothes, she had a fresh, oddly modern angularity, a wiry strength. Her bones, revealed now by the paring down age seemed to confer on some women, were long and elegant, her chin-length hair shot through with a glinting silver that only heightened her aura of indestructible glamour.