The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (37 page)

Read The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris Online

Authors: David Mccullough

Tags: #Physicians, #Intellectuals - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Artists - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Physicians - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris, #Americans - France - Paris, #United States - Relations - France - Paris, #Americans - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #France, #Paris (France) - Intellectual Life - 19th Century, #Intellectuals, #Authors; American, #Americans, #19th Century, #Artists, #Authors; American - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris (France) - Relations - United States, #Paris (France), #Biography, #History

The autumn of 1851 was particularly beautiful—like Indian summer at home, wrote a correspondent for the

New York Times

. The air was “soft and hazy, the sunlight rich and mellow.” The misery of so many was “crouching out of sight” no less than ever, off in the narrow, crooked streets, and being out of sight, was “as usual out of mind.” The well-dressed, well-fed populace filled the boulevards. The fashionable avenue of the ChampsÉlysées was as crowded as on the finest days of spring.

There was talk, of course, of political unrest, of hidden plots and coups d’état, and it seemed to matter not at all to the Parisians.

They eat, drink, and make merry, and make the most of the passing day. Future probabilities or possibilities are not allowed to interfere with the pleasures of present possession. This way of taking life is wise enough—for, remember, it is French life.

On the first day of December 1851, Louis Napoleon sent for his American dentist friend, Thomas Evans, who on arriving at the Élysée Palace found the president more than ordinarily affectionate toward him. There were, however, Evans later wrote, moments when it seemed the president had something he wished to talk about, yet did not.

At a formal reception at the palace that evening, he stood greeting his guests in his usual calm, attentive way, showing no sign that anything out of the ordinary might be on his mind. About ten he excused himself and went behind closed doors to join a small coterie of trusted fellow conspirators. As they gathered about his desk, he opened a bundle of secret papers bearing a single code word, “Rubicon.”

Soon after midnight, in the first hours of December 2, 1851, the surprise coup was under way.

Before daybreak more than seventy political figures, generals, and journalists had been roused from their beds and arrested. By dawn troops lined the boulevards and occupied the National Assembly, the railroad depots, and other strategic points. Proclamations put up on the walls of buildings proclaimed the National Assembly dissolved. The constitution

Louis Napoleon had taken an oath to uphold had been done away with and a new constitution called for.

Everything had been considered. Soldiers posted at newspaper offices kept them from opening. Even the ropes of church bells had been cut so they could not be used to summon protest.

In a matter of hours, Louis Napoleon had made himself dictator. Later that morning he rode through Paris on horseback without incident. Not for another two days did protest flare, and it was quickly, decisively crushed, leaving hundreds dead.

Two weeks later, in a national referendum, the country voted overwhelming approval of Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état.

Many were outraged. The American minister, William Rives, felt so incensed he refused to attend the president’s diplomatic receptions until gently reproved from Washington by Secretary of State Daniel Webster. Victor Hugo, who had thought well of the president at the beginning, fled to Belgium that he might speak his mind freely about “Napoleon the Little.” “On 2 December, an odious, repulsive, infamous, unprecedented crime was committed,” he wrote.

The author of this crime is a malefactor of the most cynical and degraded kind. His servants are the comrades of a pirate. … When France awakes she will start back with a terrible shudder.

Hugo would remove himself further to the English Isle of Guernsey, where he would live in exile for fifteen years.

The usual bustle of Paris resumed yet again, crowds in the streets taking up the familiar pace of business and pleasure. Many of those arrested were released. Newspapers resumed publication, though by a new decree anyone found propagating false news would be immediately arrested, which in effect meant no real freedom of the press.

Political discord and violence had been put to rest at last, it seemed, and for the greater part of the population, even in Paris, that was sufficient for now. When the words

Liberté

,

Égalité

,

Fraternité

were removed from the façades of public buildings, there was hardly a word of protest.

The following October, Louis Napoleon, age forty-four, was proclaimed Emperor Napoleon III, and the close of the year 1852 marked the official beginning of the Second Empire. To a large part of the nation, however, it was not until a bright morning in January 1853, when, at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, he married the beautiful Spanish countess Eugénie-Marie de Montijo—and France once again had both an emperor and an empress—that the Second Empire was truly under way.

As for what he intended to do with his power, the new emperor was emphatically clear on one thing above all. He would make Paris more than ever the most beautiful city in the world and solve a number of intolerable problems in the process.

The great appeal of the city had long been what man built there. There was nothing stunning about its natural setting—no mountain ranges on the horizon, no dramatic coastline. The river Seine, as Emma Willard and other Americans had noted, was hardly to be compared to the Hudson, not to say the Ohio or the Mississippi. The “genius of the place” was in the arrangements of space and architecture, the perspectives of Paris. Now far more—almost unimaginably more—was to be built, and the perspectives to become infinitely longer.

No time was taken up with extended discussion. The emperor disliked discussion. He put a new prefect of the Seine in charge, a career civil servant and master organizer named Georges-Eugène Haussmann, and the choice proved decisive. On the day Haussmann was sworn in, the emperor showed him a map on which he had drawn in blue, red, yellow, and green pencils what he wanted built, and “according to their degree of urgency.”

The work would go on for nearly twenty years. Haussmann liked to call himself a “demolition artist,” and from the way great, broad swaths were cut through whole sections of the city, and entire neighborhoods leveled with little apparent regard for their history or concern for their inhabitants, it seemed to many that headlong destruction was truly his main purpose. On the Île-de-la-Cité, the historic center of Paris, the ancient

slums clustered close to Notre-Dame would be leveled. Streets that Victor Hugo knew and wrote about in

Notre-Dame de Paris

totally disappeared. The Hôtel Dieu would be demolished without the least hesitation. “I could never forget the sinister air of that bit of river wedged between two hospital complexes with a covered walkway between them, polluted with evacuations of every kind from a mass of patients eight hundred strong or more,” Haussmann wrote. A resident population of some 15,000 people on the Île-de-la-Cité would be reduced to 5,000.

Broad avenues were to radiate from the Arc de Triomphe like the spokes of a colossal wheel. North from la Cité would run the new boulevard de Sébastopol, and south, the boulevard Saint-Michel. In a long east-west arc on the Left Bank, back from the river, a broad thoroughfare, the new boulevard Saint-Germain, would cut through the heart of the old Latin Quarter.

Haussmann was vigorous and opinionated, a broad-shouldered man, six feet two, who could be ruthless with anything or anyone standing in his way—as often said, just the sort who might succeed in such an ambitious and difficult task.

With its population now more than a million people and still growing, the city had urgent need of modern improvements. Its problems were many and serious. The old tangle of medieval Paris, the crowding, the filth, squalor, foul air and water could be ignored no longer if only for the physical health of the people. It was not that no notable progress had been accomplished in recent years. Much had been done for the betterment of city life under Louis-Philippe. But far more was needed.

The plan was to improve public health and reduce crime, improve the flow of traffic and commerce, provide better sanitation with a vast new sewer system, improve the city’s water supply, and provide more open space and clean air, as well as years of employment for tens of thousands of workers. It was true that straight, wide streets would be less suitable for building barricades and better for the rapid deployment of troops, or for directing artillery fire, as critics often said. But a free flow of traffic and a sense of grandeur were far more important to the planners. The making of a more splendid city was always the paramount objective. The longest of the boulevards planned, the rue Lafayette, was to run three miles in a

perfectly straight line. Eventually seventy-one miles of new roads would be built.

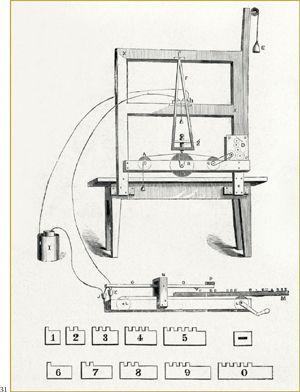

Samuel F. B. Morse’s first telegraph.

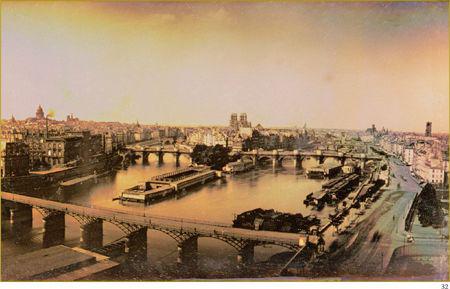

Early daguerreotype of Paris, with the Pont des Arts in the foreground, the Pont Neuf and the towers of Notre-Dame in the distance.

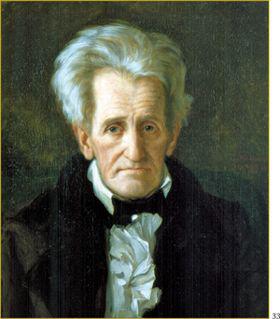

Andrew Jackson

by George P. A. Healy. Painted in Tennessee only days before Jackson’s death in 1845. Jackson was one of several prominent Americans painted by Healy at the request of King Louis-Philippe of France.