The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris (40 page)

Read The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris Online

Authors: David Mccullough

Tags: #Physicians, #Intellectuals - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Artists - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Physicians - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris, #Americans - France - Paris, #United States - Relations - France - Paris, #Americans - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #France, #Paris (France) - Intellectual Life - 19th Century, #Intellectuals, #Authors; American, #Americans, #19th Century, #Artists, #Authors; American - France - Paris - History - 19th Century, #Paris (France) - Relations - United States, #Paris (France), #Biography, #History

Raoul Rigault dead in the gutter.

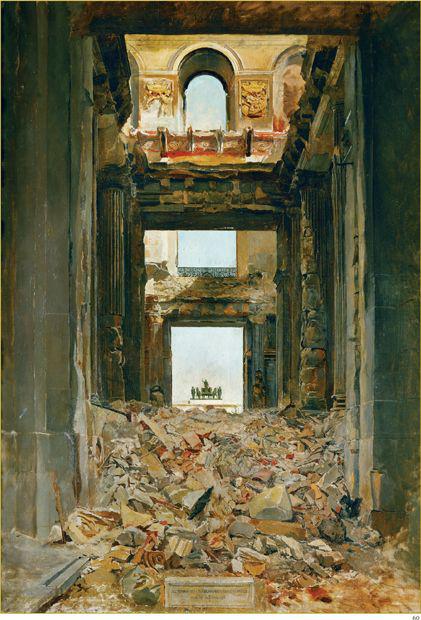

The Ruins of the Tuileries Palace

by Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier.

Along the great boulevards new apartments would rise—whole apartment blocks of white limestone—none more than six stories high and in a uniform Beaux-Arts architectural style, with high French windows and cast-iron balconies. Sidewalks were to be widened. Streets and boulevards would be lined with trees and glow at night with 32,000 new gas lamps. Gaslight everywhere would turn night into day, making Paris truly

la ville lumière.

And with the boulevards came such novelties as newspaper kiosks, public urinals, and cafés with their tables and chairs set outside on the sidewalks.

The emperor directed that the Bois de Boulogne, the vast woodland west of the city, must become a public park surpassing that of any city, and include a magnificent approach, the avenue de l’Impératrice—the avenue of the Empress. Miles of new walking paths, flower beds, lakes, and a waterfall were part of the plan. And other, smaller parks were to be developed, such as the beautiful Parc Monceau.

“At every step is visible the march of improvement,” Haussmann wrote proudly in his diary. But the gulf between the rich and the poor grew greater, and as Haussmann himself acknowledged, over half the population of Paris lived still “in poverty bordering on destitution.”

The Louvre would be completed at last. New libraries were built. A new Palais de Justice would rise on the Île-de-la-Cité, and in time an all new Hôtel Dieu. For all that was lost to demolition on the Île-de-la-Cité, an essential part of the plan was to keep it the heart of the city, and much of historic importance was spared. With most of the dense slums removed, the glorious façade of Notre-Dame would stand in a wash of open light and in full view as it never had.

Les Halles, a great new central market, with cast-iron girders and a skylight roof, would go up, and as a kind of architectural crescendo, the grandest, most exuberant expression of the Second Empire opulence, a new Théâtre de l’Opéra at the head of a new avenue de l’Opéra, was to be the surpassing centerpiece of the new Paris.

Clouds of dust and mountains of rubble became part of the scene. Traffic would be brought to a halt on the rue de Rivoli by the accidental shattering of a water main. The removal of paving stones on the Place du Panthéon revealed an ancient underground cavity very like the cata-combs. With the demolition of an old convent, the skeletons of eleven nuns were exhumed, some still retaining parts of their woolen habits. Workers were badly injured or killed in accidents.

To be sure, not all were pleased with the transformation. When a character in an English novel of the time,

The Parisians

by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, asked, “Is there not something drearily monotonous in these interminable perspectives?” more than a few readers nodded in agreement.

“How frightfully the way lengthens before one’s eyes!” the same character, a French

vicomte

, continued.

In the twists and curves of the old Paris one was relieved from the pain of seeing how far one had to go from one spot to another; each tortuous street had a separate idiosyncrasy; what picturesque diversities, what interesting recollections—all swept away!

Mon Dieu!

And what for?

The cost of it all, exceeding even the most extravagant expenditures of times past, was to be met with some government funds and a great deal of borrowed money. By 1869 some 2.5 billion francs would be spent, forty times the cost of Louis-Philippe’s improvements. Such an investment, it was promised, would be more than compensated for by increasing prosperity. “When building flourishes, everything flourishes in Paris,” went an old saying. And with order and prosperity the people might continue to forget the loss of their essential liberties.

Contrary to what many assumed, neither the emperor nor Haussmann profited personally from the project, though certainly others close to the emperor did, and handsomely, including the American dentist Thomas Evans. Acting on “inside” information, Evans purchased land that would rise thirty times above what he paid for it. He would, as well, build his

own grand mansion on the broad new boulevard leading from the Place de l’Étoile, where the Arc de Triomphe stood, to the entrance of the Bois de Boulogne.

That the final splendor achieved would make Paris more appealing than ever, few had any doubt.

The number of visitors was already increasing noticeably in the early 1850s. Railroad service to and from the rest of Europe and French ports on the Channel was by now well established, clean, and efficient. At sea, larger and ever-finer steamships were crossing from America on regular schedules year-round, and offering comforts on board unimaginable only a few years earlier. The change was dazzling.

American steamers like the

Atlantic, Pacific

, and

Arctic

of the Collins Line were appropriately called “floating palaces.” The

Arctic

, as an example, offered accommodations for 200 first-class passengers, a grand dining salon, a gentlemen’s smoking room, a gentlemen’s barber shop. Interiors were richly embellished with satinwood and gilded ceilings, plush armchairs, oversized mirrors, marble-topped tables. On the

Pacific

, where the décor was equally resplendent, five especially large staterooms were designated bridal suites, and the wine cellar carried more than 3,000 bottles.

Such ships were steam-heated for winter travel and featured indoor plumbing. Ice rooms carried as much as forty tons of ice. Fresh fish, fruits, and vegetables were staples. The cooking was comparable to that of the best restaurants. There were no steerage passengers aboard such vessels, and first-class passage was predictably high-priced, about $150 one way. (For an additional $24 one could bring a dog.) “God grant the time will come when all mankind shall be as luxuriantly cared for at home as they are when they go abroad,” wrote a New York correspondent describing life aboard the

Arctic

.

The great majority of those crossing the Atlantic in both directions still traveled by sailing ships, and by far the greatest number of those passengers were headed in the opposite direction from Americans bound for France. They were sailing for America in steerage, fleeing famine in Ireland

and revolution in Europe—over 200,000 Irish in the peak year of 1851, and even more, 350,000, from Germany in 1853 and 1854.

Still, the number of Americans who could afford to travel by luxury steamships and enjoy comparable accommodations once abroad, was steadily on the rise, and even more were now giving the idea serious consideration. In 1851, largely because of interest in the Great Exposition at London’s Crystal Palace, the

Pacific

put out from New York carrying 238 passengers, a new steamliner record for a single crossing.

Many who were headed for London went on to Paris, and increasingly the more affluent of them brought their families. No longer was it uncommon, as in the time of James Fenimore Cooper, to see a husband and wife come aboard with three or four young children, as well as a servant or two.

Among the earliest of such couples were Robert and Katherine Cassatt of Pennsylvania, who in the summer of 1851 embarked on an extended sojourn abroad, stopping first in London before moving on to Paris with their three young children, Alexander, Lydia, and Mary. In Paris they settled in for an extended stay at the Hôtel Continental, and seven-year-old Mary was to remember the day of Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état the rest of her life. It would also be said that her interest in painting began then, which would appear to make her the youngest American thus far to have come under the spell of the arts in Paris.

Two years later, in the spring of 1853, another notable but very different American family began its time abroad.

The year before, in 1852, a new novel titled

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

by an unknown author had caused the greatest stir of anything published in America since Thomas Paine’s

Common Sense

. The book had since become a sensation in Britain as well, and its author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, unknown no longer, was on her way to England in the “hope of doing good” for the cause against slavery, as she had told her friend Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

In Britain,

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

had been acclaimed for having accomplished greater good for humanity than any other book of fiction. Over

half a million British women had signed a petition against slavery. In Paris, where the Stowes were also headed, publishers were still scrambling to finish translations, but George Sand, writing in

La Presse

, had already called Mrs. Stowe “a saint. Yes—a saint!”

Traveling with her were her husband, the preacher-scholar Calvin Stowe, her younger brother, Charles Beecher, also a preacher, and three of her in-laws, but none of her children. They crossed on the steamship

Canada

, and for Hatty, as she was known in the family, it was, at age forty-one, her first time at sea.

The author’s British tour was long and exhausting. Having taken no part in the antislavery movement prior to writing her book, she suddenly found herself the most influential voice speaking on behalf of the enslaved people of America. From the day her ship docked at Liverpool, crowds awaited her at every stop of the tour through England and Scotland. Husband Calvin was so undone by it all that he gave up and went home.

By the time Hatty reached Paris, in the first week of June, she craved only some peace and privacy, and wanted her presence in the city kept as quiet as possible. Rather than staying at one of the fashionable hotels, she moved into a private mansion on the narrow rue de Verneuil in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, as the guest of an American friend, Maria Chapman, known as “the soul” of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society.

“At last I have come into a dreamland,” Hatty wrote. “I am released from care. I am unknown, unknowing. …”

With her time all her own, she used it to see everything possible, starting the next day, a Sunday, with church service at the Madeleine, her first “Romish” service ever. She usually went accompanied by her brother Charles, whose energetic, good-humored companionship she relished. For nearly three weeks she moved about Paris unnoticed, a small, fragile-looking woman of no apparent importance—“a little bit of a woman,” as she said, “about as thin and dry as a pinch of snuff, never very much to look at in my best days.”

She was tireless and saw everything that so many Americans had seen before her, but took time to look hard and to think about what she saw. Hatty was a natural “observer,” wrote Charles, “always looking around on

everything.” And for all that others had had to say on the same subjects, there was a freshness, an originality in what she wrote.