The Grim Ghost (2 page)

The kitchen door was already open, but there was no cooling breeze inside. Pliny moved out and sat on a bench in the shade of a tree.

Augusta took a silver goblet, stepped into the dark, chilly larder and dipped it into a barrel of cool ale. She carried it into the garden. Pertinax followed.

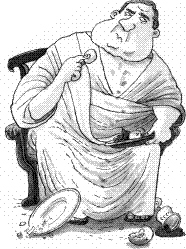

“There you go, master,” the cook smiled. “Stop worrying. Remember, when I was a girl I helped cook for the Emperor Vitellius. What a man! What an eater! We made banquets like yours three or four times every day. That man was a glutton. He lived for food.”

Pliny sipped at the ale and nodded. “I have heard the stories about him. He died when I was just six years old, so I never met him. But he was famous for his eating.”

“Famous and foul,” said Augusta. “It was murder cooking for him, I can tell you.”

“Why, Grandma?” Pertinax asked.

“Because it was a waste.”

“Didn’t he like your food?”

“He liked it

too

much,” Augusta sighed.

Pliny nodded. “They say he would eat and eat till his stomach was full. Then he would take a large bowl and push a long feather into his mouth. He’d tickle the back of his throat till he threw the food back up. When his stomach was empty, he’d start eating all over again.”

“What a wicked waste,” Augusta moaned. “The slaves would have enjoyed that food. Or the poor people of Rome.”

Pliny snorted. “Of course it wasn’t just the poor people who hated his habits. He used the Roman navy to sail the world and find him new treats. At one feast, they say he had 2,000 fish and 7,000 birds.”

“Parrots?” Pertinax asked.

“Probably,” Pliny nodded. “I wasn’t there.”

“But

I

was,” Augusta reminded him. “Vitellius was very fond of the rarest foods, like pike livers, pheasant brains and flamingo tongues.

“In the end, the Roman people became tired of his silly ways – they sent an army to kill him.

“Vitellius tried to hide in a cupboard at the temple. They dragged him out, hacked him to death and threw his body into the River Tiber.”

Pliny chuckled. “His fat corpse must have made a fine feast for the fish. The pike had their revenge. Ha!”

Pertinax looked at the parrots on the table, and then up at Master Pliny. “My grandma says you want to eat the parrot heads,” he said, shyly. “Why?”

“Sorry, sir,” Augusta said. “The boy doesn’t understand. Food has to

look

exciting as well as taste delicious. It has to look so exciting that the guests

talk

about it. Parrot heads add a lot of colour to a feast. Now, excuse me, sir, we should get back to the kitchen.”

“Leave the boy here for a while,” her master said. “He is good company.”

Augusta bowed and went back into the scorching kitchen.

“But you can’t

eat

parrot heads,” Pertinax argued. “You can’t chew the feathers – and the beak would break your teeth!”

Pliny sipped his ale and smiled. “The guests use a small spoon to scoop out the boiled brains and eat them.”

“Is that why we have so many birds in cages in the kitchen? Will they all have their brains eaten?” Pertinax asked.

“No,” Pliny said. “Remember what your grandmother said about exciting food? Well, when the wild boar has cooled, we’ll pop a dozen birds inside the empty boar and stitch it up. When the slaves carve open the boar at the feast, the birds will fly out!”

“Old fat-guts Vitellius would have enjoyed that,” the boy said.

“I’m sure he’ll be there tonight,” Pliny murmured.

“But he’s dead!”

“His spirit still lives on. When we die, our spirit remains, you know.”

Pertinax shivered. “Ghosts? I’ve heard of them. But they join the gods on their mountain, don’t they?”

Pliny blew out his cheeks. “Not all of them. Some stay behind and are doomed to haunt this earth. In fact there was one in this very garden…”

Pertinax gasped. “Have you seen it? Have you seen the ghost, Master Pliny?”