The Guild of the Cowry Catchers, Book 1: Embers, Deluxe Illustrated Edition (3 page)

Read The Guild of the Cowry Catchers, Book 1: Embers, Deluxe Illustrated Edition Online

Authors: Abigail Hilton

Tags: #gay, #ships, #dragons, #pirates, #nautical, #cowry catchers, #abigail hilton, #abbie hilton, #fauns

“Go.”

Morchella lingered a moment, staring into the

empty pool. Outside, the sun was setting, playing streamers of

soft, colored light across the gently undulating water. “Thessalyn…

Gerard, you do not know it, but you have saved her life

tonight.”

The minstrels of Wefrivain are

quasi-religious figures, schooled in the old stories. Their role in

society is not only to entertain, but also to encourage religious

devotion.

—Gwain,

The Truth About Wyverns

Gerard found his friend and mount, a griffin

named Alsair, waiting for him outside the Priestess’s Sanctum.

Wordlessly, they walked through the Temple complex and then out

into the streets of Dragon’s Eye.

“Well?” demanded Alsair as they started into

the press of shelts coming and going in the late afternoon

rush.

Gerard shook his head.

“What did she say? What was it about?” Alsair

butted Gerard playfully with his beak. Their heads came to the same

height when they were both standing. “You can’t say nothing, not

after an audience like that.” They had been together since

childhood. Gerard’s silences were legendary, but Alsair had always

been good at making him talk, and when that failed, Alsair could

always fill the silences.

Gerard shook his head. “Not now.”

They were coming to the market. Throngs of

shelts hurried home as the day ended. They were mostly grishnards.

A few shavier fauns—pegasus shelts—moved furtively in the press.

They were probably the slaves of great houses. All the shelts—both

grishnard and faun—had long, tufted ears that flicked back against

their heads at the flies and the noise.

As Gerard and Alsair drew closer to the

docks, the numbers of non-grishnard shelts increased. A filthy

urchin, probably a pickpocket, darted across the road, and they saw

the flash of his red fox tail. “There goes a long-lost relative of

our dear admiral,” muttered Alsair nastily. “Shall we invite him to

the ship and ask their relation?”

Gerard did not honor this with a reply.

Silveo Lamire was a fox shelt. Rumor had it he’d risen to his post

from the slums around the docks.

“Did he do you a favor by trying to kill

you?” asked Alsair. “Was the priestess impressed with what you

could do with one row boat and a few rowers? Especially when you’d

been intentionally stranded among enemies?”

“We don’t know Lamire intentionally stranded

me,” said Gerard. He strongly suspected it, but he did not

know.

“Well I do,” said Alsair. “He locked me in

the hold.”

“Anyone could have done it, perhaps even by

accident.”

“You know as well as I do that Lamire ordered

it,” growled Alsair, “and someday, I’ll pay him back.” He made a

sharp clicking noise with his beak.

Gerard frowned. “Stay away from him, Alsair.

He’s afraid of griffins, and Lamire is the sort of shelt who gets

vicious when he’s frightened.”

They stopped in front of an inn—the grandest

on the waterfront, with high, arched ceilings reminiscent of some

noble’s audience hall. Two hulking grishnards loitered near the

entrance, making sure that none of the dock’s riffraff bothered the

patrons. Every shelt within was almost certainly a grishnard.

Alsair snickered. “Do you think they’d toss Lamire off the dock if

he came here without his insignia and bodyguard?”

“Probably.” Gerard pushed open the door. “I

don’t want to talk about him anymore.”

“But you haven’t,” complained Alsair. “Only I

have.”

“Hush.”

At the far end of the long, elegant common

room, someone was singing to the music of a harp. Her voice had the

haunting quality of doves at dawn or the high and lonely cry of a

falcon. She sang one of the temple songs about wyverns and their

coming to the islands of Wefrivain. She sang all the verses—the

very old ones, unfamiliar to most shelts. She sang of the terrible

wizards—shape-shifters, mind-parasites, slavers. They had come upon

the islands in ages past, and they brought fear and pain and death.

She sang of how the Firebird had sent the wyverns to free the

shelts of Wefrivain. The song might have been dry as dust in the

mouth of some temple harpist, but for her the song opened like a

flower.

“Go stretch your wings, friend,” Gerard told

Alsair. “Hunt on the ocean. I’ll envy you.”

Alsair snorted. “You won’t even

think

of me.”

But Gerard was already gone. He forced his

way through the crowd around the singer, using his height and broad

shoulders to muscle them aside.

She was a grishnard with glossy golden fur

and hair so pale it looked almost white in the lamplight. Her eyes,

too, were white, and they shone as though she saw visions and not

the crowd around her. In truth, she did not see them, for she was

blind.

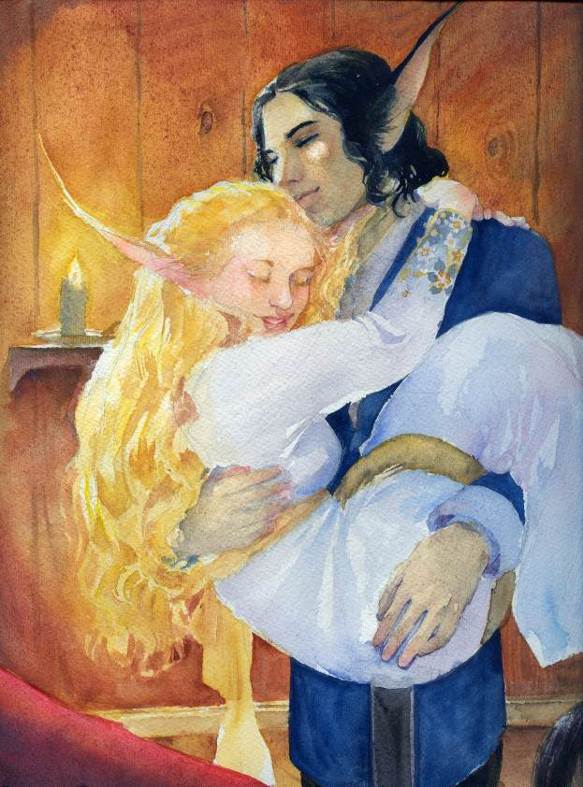

As the last notes of the song faded, Gerard

reached her and scooped her up in his arms, catching the harp with

one hand. Several shelts in the crowd protested, but Gerard ignored

them and carried her away. At the foot of the stairs, the innkeeper

met him with more protests. “My wife,” said Gerard, “has more than

filled your hall. She’s paid for our room ten times over. Good

night.”

Thessalyn nestled against his chest. “Did you

see her?” she whispered. “Did you see the Priestess?”

“I saw her,” said Gerard. He did not speak

again until he’d reached their room and unlocked the door. “I saw

her and I spoke to her. She is beautiful and terrible, as they say,

but she was not as beautiful as you.”

Thessalyn smiled and shook her head. She had

never seen her own beauty, for she had come sightless into the

world. Gerard had always found that a great paradox. “No one sees

like you do,” he’d told her once. “I think sometimes you have the

gift of prophesy.” She denied that, but she did not deny she had

the gift of song. Thessalyn had been born to one of the tenet

farmers on a little island holding of Holovarus. Many farmers would

have drowned a blind baby girl—a useless mouth in their world of

labor—but her father was gentle and soft-hearted, and music ran in

his blood.

By the age of five, it was apparent that she

had a great gift, and the family had struggled to save enough to

send her to the prestigious school of minstrels on Mance. They

found the money, but a recommendation was required from a reputable

source. The family boldly petitioned their lord, Gerard’s father,

to listen to the child and recommend her to the school. He did

both. He even paid for her books and supplies and finally for her

tuition when her family fell on hard times the next year.

Thessalyn charmed everyone, including her

teachers. She made her debut tour at fourteen and soon had a throng

of potential patrons, but she chose to return to her family seat.

Holovarus welcomed her as court minstrel. Her beauty, her

blindness, her imagination, and her splendid voice had made her one

of the most famous minstrels in Wefrivain, and little Holovarus

basked in the prestige she brought with her.

Her success made her a great asset to the

court and a worthy investment to the King. However, it did not make

her a suitable mate for the prince. If Gerard had been content to

dally with her, his father might have taken no notice, but marriage

was different. Thessalyn might be beautiful and talented, but she

worked for her living, and she brought no dowry. Gerard did not

like to think about that last year, so full of darkness and grief.

Thessalyn might be able to forgive the gods, and he did not

begrudge her the peace her faith brought her. She might talk of

higher purposes, but Gerard could never forgive what had happened

in the temple on Holovarus.

We’ve come far since that night,

he

reminded himself. It was ironic that he’d retreated into the Temple

Sea Watch, but Gerard thought of himself as a servant of the

Priestess, not of the wyverns. The Sea Watch offered an honorable,

if humble, escape from his family. His problems with his commanding

officer, Silveo Lamire, were nothing to the churning sea of

troubles he’d left on Holovarus.

Gerard set aside Thessalyn’s harp—a

confection of dark, curling wood, half as big as the girl who

played it. She nipped at his ear and he kissed her, but then set

her down gently on the bed and stretched out beside her. “You’re

tired,” she said, stroking his ink-black hair. “And worried. What’s

wrong, Gerard?”

He spoke in a near whisper. “Sing to me,

Thess. Please.”

So she sang, in a very soft voice, an

achingly sad lullaby for the child they had lost. (Thessalyn had

the gift of knowing when he did not wish to be cheered.) Yet, like

most of the songs she composed herself, the end was full of light

and distant shores and coming home. Gerard made her stop at last.

“I have to go.”

“Where?”

“To the dungeons. I have to help Silveo

Lamire interrogate prisoners.”

She stroked his cheek. “Why, love?”

“Because I am her Highness’s new captain of

Police.”

Thessalyn’s fingers stopped moving. A long

silence, then, “It is work that someone must do. The Police protect

us.”

“The Police drag shelts from their homes in

the middle of the night to pull out their fingernails in

basements,” snapped Gerard. He felt her tremble and regretted it at

once. “Forgive me. I didn’t come here to make you sad.”

“You are

good,”

said Thessalyn softly.

“Good things cannot be evil.”

Gerard sighed. “I don’t know about good. I

certainly am what I am, and I cannot seem to be otherwise. I will

do what I am able. Perhaps I can make the Police into something

more than an ugly threat. It’s no wonder their captains keep

disappearing.”

He stood and kissed her fingertips. “Thank

you, my dear.”

“I’ll be waiting for you,” said Thessalyn.

“However late you come.”

“Or whatever I’ve done in the meantime?”

“Or whatever you’ve done in your

lifetime.”

Those with paws eat those with hooves. Just

as pegasus are food for griffins, so fauns are food for grishnards.

This is right and natural.

—Morchella,

Sacred Text

As Gerard suspected, Silveo had already come

to have a look at the prisoners. Gerard found him in the hallway of

the temple dungeons, haranguing the unfortunate guard. “Have you

been living under a rock for the last ten years?” demanded Silveo.

“Do you not know who I am?”

“I know who you are, and I cannot allow you

to enter. The Priestess has forbidden you access to these

prisoners.”

“Can you let me in?” asked Gerard.

Silveo spun around to glare at him. He was a

silver-furred fox shelt with hair of the same color and pale blue

eyes. He was a vain creature with a plume of a tail, braided

frequently with ribbon or gold thread. His eyes were lined with

more kohl than Gerard thought seemly or necessary to reduce the

glare of the sun. In apparel, Silveo had the unfortunate tastes of

the newly wealthy. His clothes were frequently heavy with cloth of

silver, pearls, and exotic furs. Gerard’s taste for elegant

understatement seemed to annoy him.

In fact, nearly everything about Gerard

seemed to annoy Silveo. Fox shelts were one of the little races.

Adults stood no taller than a ten year old grishnard child. Silveo

had to look up at most grishnards, but with Gerard, he had to look

even higher. Gerard suspected this had been the original source of

Silveo’s enmity. However, they hadn’t taken long finding other

reasons to dislike each other.

Gerard spoke to the guard at the cell door.

“My name is Gerard Holovar, and I think you’re supposed to let me

interrogate the prisoners.”

“That is correct,” said the guard. “Her

Highness left instructions.”

Gerard glanced at Silveo’s confused

expression. “I have been made captain of Police,” he explained.