The Happiness Project (33 page)

Read The Happiness Project Online

Authors: Gretchen Rubin

I’d read about a “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” class that claimed to be able to change the way in which people processed visual information so anyone could learn to draw. Perfect. I figured that, as with laughter yoga, I’d be able to find a “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” class in Manhattan, and sure enough, the class was offered by the program’s principal New York instructor, right in his own apartment in SoHo. I “indulged in a modest splurge,” signed up, and for five days took the subway downtown for a day that started at 9:30

A.M

. and ended at 5:30

P.M

.

Novelty and challenge bring big boosts in happiness. Unfortunately, novelty and challenge also bring exhaustion and frustration. During the class, I felt intimidated, defensive, and hostile—at times almost panicky

with anxiety. I felt drained each night, and my back hurt. I’m not sure why it was so stressful, but trying to follow the instructor’s directions, squint, measure against my upheld thumb, and draw a straight line on a diagonal, was physically and even emotionally taxing. One person in our little class had a kind of breakdown and quit after three days. Yet it was also tremendously gratifying to learn something new—to partake of the atmosphere of growth.

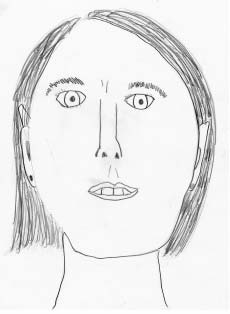

I drew this self-portrait on the first day of class. Later, when I showed it to a friend, she said, “Come on, admit it. Didn’t you do a bad job on purpose, to make any progress you made look more dramatic?” Actually, nope. This was my best effort.

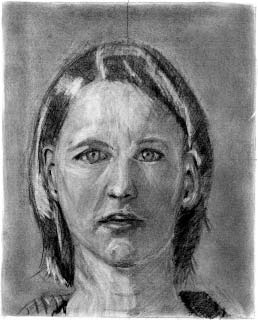

I drew this self-portrait on the last day of class. My instructor helped me with all the hard parts, and it doesn’t actually resemble me very much, but it does look like a portrait of a person.

Drawing exercised an unaccustomed part of my brain, but apart from that, just the fact that I was taking a class boosted my mindfulness. Being in a different neighborhood at an unusual time of day heightened my awareness of my surroundings; New York City is so beautiful, so endlessly compelling. The rhythm of the day was very different from my typical schedule. I enjoyed meeting new people. Plus—the class worked! I drew my hand, I drew a chair, I drew a self-portrait that, although it didn’t look much like

me,

did look like an actual person.

The drawing class was a good illustration of one of my Secrets of Adulthood: “Happiness doesn’t always make you

feel

happy.” Activities that contribute to long-term happiness don’t always make me feel good in the short term; in fact they’re sometimes downright unpleasant.

From drawing, I turned to music—another dormant part of my mind. According to research, listening to music is one of the quickest, simplest ways to boost mood and energy and to induce a particular mood. Music stimulates the parts of the brain that trigger happiness, and it can relax the body—in fact, studies show that listening to a patient’s choice of music during medical procedures can lower the patient’s heart rate, blood pressure, and anxiety level.

Nevertheless, one of the things that I’ve accepted about myself, as part of “Being Gretchen,” is that I don’t have much appreciation for music. I

wish

I enjoyed music more, but I don’t. Every once in a while, though, I fixate on a song I really love—recently I went through an obsession with the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ “Under the Bridge.”

The other day, while writing in a coffee shop, I overheard a song that

I love but had forgotten about: Fatboy Slim’s “Praise You.” I went home, loaded it onto my iPod, and listened to it that night while I was cleaning my office. This song flooded me with tender feelings for Jamie. Yes, we have gone through the hard times and the good! Yes, I have to praise him like I should! This would have been a good activity for February, the month of marriage.

I thought again about Jung playing with blocks to recapture the passionate engagement of his boyhood. When I was little, I used to dance around the room to my favorite music. I was too young to read, so I asked my mother to mark the record of

The Nutcracker Suite

so I’d be able to find it. But I stopped dancing when I got older. Maybe I should try dancing around the room again.

I didn’t want anyone walking in on me while I was doing it, and it took a long time before I had an opportunity. I hadn’t realized before how rare it was for me to be home alone. Finally, one Sunday afternoon, I told Jamie I was going to stay behind when he took the girls around the corner to visit his parents. After the apartment was empty, I went into our bedroom, turned off the lights, lowered the blinds, and put my iPod into an iPod speaker base. I had to squelch thoughts of self-criticism—that I was a bad dancer or looked goofy.

It was fun. I did feel goofy, but I also felt energized and exhilarated.

I started thinking more about music. I thought I’d accepted the fact that, as part of “Being Gretchen,” I didn’t really like music, but in fact, the truth was slightly different: I thought I didn’t like music, but in fact, I didn’t approve of my own taste—I wished I liked sophisticated music, like jazz or classical or esoteric rock. Instead, my taste ran mostly to what might play on a lite FM station. Oh, well. Be Gretchen.

Listening and dancing to music absolutely boosted my feelings of mindfulness. I felt much more aware of music during the day; as I worked in a diner, I really

heard

Abba singing “Take a Chance on Me” over the loudspeaker. This heightened responsiveness to my environment made me

feel more present in the moment. Instead of tuning music out, I made music a bigger part of my experience.

KEEP A FOOD DIARY.

I also wanted to apply the principles of mindfulness in a much less elevated context: my eating habits. Studies show that merely being conscious of eating makes people eat more healthfully, and one way to encourage yourself to eat more mindfully, experts agree, is to keep a food diary. Without a record, it’s easy to overlook what you eat without noticing it—grabbing three Hershey’s Kisses every time you pass a coworker’s desk throughout the day or eating leftovers from other people’s plates as you clear the kitchen table. In one study, dieters who kept a food diary lost twice as much weight as dieters who didn’t bother.

I’d felt guilty for a long time about my mediocre eating habits, and I wanted to eat more healthfully, plus I wanted to lose a few pounds without going on a diet (hardly an original goal—almost seven out of ten Americans say they’re trying to eat healthfully to lose weight). Making notes about the food I ate sounded easy enough, and I figured that, of all my various resolutions, this would be one of the easier ones to keep. I bought myself a little notebook.

“I keep a food diary,” a friend told me at lunch soon after, when I mentioned my latest resolution. She showed me her calendar, which was crammed with tiny writing detailing her daily intake. “I update it every time I eat.”

“They say that keeping a food diary helps you eat better and lose weight,” I said, “so I’m giving it a try.”

“It’s a great thing to do. I’ve been keeping mine for years.”

Her recommendation reassured me that the food diary was a good idea. My friend was thin and fit, plus she was one of the healthiest (if also one of the most eccentric) eaters I knew. I’d just heard her order lunch.

“I’d like the Greek salad, chopped, no dressing, no olives or stuffed grape leaves, plus a side order of grilled chicken and a side order of steamed broccoli.” When the food arrived, she heaped the chicken and broccoli onto the salad. It was a

lot

of food, but tasty and very healthy. I ordered the same salad, but without the extra chicken and broccoli. Before we dug in, we sprinkled artificial sweetener over our salads. (She taught me this trick. It sounds awful, but artificial sweetener makes a great substitute for dressing. It’s like adding salt; you don’t taste it, but it brings out the flavor of the food.)

“I refuse to go on a diet,” I told her.

“Oh, me too!” she said. “But try keeping a food diary. It’s interesting to see what you eat over the course of a week.”

I tried it. My problem: I found it practically impossible to remember to keep a food diary. I’ve read repeatedly that it takes twenty-one days to form a habit, but in my experience, that just isn’t true. Day after day, I tried, but only rarely did I manage to remember to record everything I ate in a day. One problem with not being very mindful, it turns out, is that you have trouble keeping your mindfulness records. Nevertheless, even attempting to keep a food diary was a useful exercise. It made me more attuned to the odds and ends I put into my mouth: a piece of bread, the last few bites of Eleanor’s lasagna.

Most important, it forced me to confront the true magnitude of my “fake food” habit. I’d pretended to myself that I indulged only occasionally, but in fact I ate a ton of fake food: pretzels, low-fat cookies or brownies, weird candy in bite-sized portions, and other not-very-healthy snacks. “Food that comes in crinkly packages from corner delis,” as one friend described my weakness. I liked eating fake food, because when I got hungry during the day, it was more convenient to grab something fake than to sit down to eat proper food like soup or salad. Plus, fake food was a treat. I’d never buy a real chocolate chip cookie or a candy bar, but I couldn’t resist the supposedly low-cal version.

Even though I knew that this kind of food was low in nutrition and

high in calories, I kept eating it, and this habit was a daily source of guilt and self-reproach. Each time I thought about buying some fake food, I told myself that I shouldn’t—but then I did anyway. I’d tried and failed to give up fake food in the past, but the food diary, incomplete as it was, made me aware of how much fake food I was eating.

I gave up fake food cold turkey—and it felt good to give it up. I’d thought of these snacks as treats and hadn’t realized how much “feeling bad” they’d generated—feelings of guilt, self-neglect, and even embarrassment. Now those feelings were gone. Just as I’d seen in July, when I was thinking about money, keeping a resolution to “Give something up” can be surprisingly satisfying. Who would have thought that self-denial could be so agreeable?

I told my sister what I’d done, and she answered, very sensibly, “You basically eat a very healthy diet, so why give up fake food altogether? Limit yourself to a few treats each week.”

“Nope, can’t do it!” I told her. “I know myself too well to try that.” When it comes to fake food, I’m like Samuel Johnson, who remarked, “Abstinence is as easy to me as temperance would be difficult.” In other words, I can give something up altogether, but I can’t indulge occasionally.

It’s true, I have a very particular definition of “fake food.” I still drink a huge amount of Diet Coke and Fresca; I still use a ton of artificial sweetener. I also eat a fair amount of candy, which I consider real and not fake. But no more crinkly packages from corner delis, and that’s a real step forward. Bananas, almonds, oatmeal, tuna sandwiches, and salsa on pita bread are filling the gap.

My fake-food experience showed me why mindfulness helps you break bad habits. When I became truly aware of what I was eating, I found it much easier to change the automatic choices I’d been making. Two or three times a day, I’d mindlessly been picking up snacks in corner delis—but when I was confronted with what I was doing, I wanted to stop. And it was only after I’d kicked my fake-food habit that I realized what a drain it had been on my happiness. Every day I’d

felt uncomfortable twinges of self-reproach, because I knew that kind of food wasn’t healthy. Once I stopped that habit, that relentless source of bad feeling vanished.

The mindfulness resolutions for October had been interesting and productive and had boosted my happiness considerably, but more important, my increased awareness had led me to an unrelated yet significant realization: I was at risk of turning into a happiness bully.

I’d become much more sensitive to people being negative, indulging in knee-jerk pessimism, or not having—what seemed to me—the right spirit of cheerfulness and gratitude, and I felt a strong impulse to lecture, which I didn’t always manage to resist. Instead of following June’s resolution to “Cut people slack,” I was becoming more judgmental.