The Hare with Amber Eyes (12 page)

Read The Hare with Amber Eyes Online

Authors: Edmund de Waal

By the time of Viktor and Emmy’s marriage in 1899 there were 145,000 Jews in Vienna. By 1910 only Warsaw and Budapest had a larger Jewish population in Europe; only New York had a larger Jewish population in the world. And it was a population like no other. Many of the second generation of the new migrants had achieved remarkable things. Vienna was a city, said Jakob Wassermann at the turn of the century, where ‘all public life was dominated by the Jews. The banks. The press, the theatre, literature, social organisations, all lay in the hands of the Jews…I was amazed at the hosts of Jewish physicians, attorneys, clubmen, snobs, dandies, proletarians, actors, newspapermen and poets.’ In fact, 71 per cent of financiers were Jewish, 65 per cent of lawyers were Jewish, 59 per cent of doctors were Jewish and half of Vienna’s journalists were Jewish. The

Neue Freie Presse

was ‘owned, edited and written by Jews’, said Wickham Steed in his casually anti-Semitic book on the Hapsburg Empire.

And these Jews had perfect façades – they vanished. It was a Potemkin city and they were Potemkin inhabitants. Just as this Russian general had put a wood-and-plaster town together to impress the visiting Catherine the Great, so the Ringstrasse, wrote the young firebrand architect Adolf Loos, was nothing but a huge pretence. It was

potemkinsch

. The façades bore no relation to the buildings. The stone was only stucco, it was all a confection for parvenus. The Viennese must stop living in this stage-set ‘hoping that no one will notice they are fake’. The satirist Karl Kraus concurred. It was the ‘debasement of practical life by ornament’. What was more, through this debasement, language had become infected by this ‘catastrophic confusion. Phraseology is the ornament of the mind.’ These ornamental buildings, their ornamental disposition, the ornamental life that went on around them: Vienna had become orotund.

This is a very complex place to send the netsuke to, I think, as I circle back to the Palais Ephrussi towards dusk, feeling calmer. It is complex because I’m not sure what all this ornament means. My netsuke are one material or another, boxwood or ivory. They are hard all the way through. They are not

potemkinsch

, not made of stucco and paste. And they are funny little things, and I can’t see how they will survive in this self-consciously grandiloquent city.

But then again, no one could accuse them of being practical, either. They can certainly be thought of as ornamental, even as a sort of enchantment. I wonder at the appropriateness of Charles’s wedding-present once it reaches Vienna.

When the netsuke arrived at the Palais, the house was almost thirty years old, built around the same time as the Hôtel Ephrussi in the rue de Monceau. The building is a piece of theatre, a show-stopping performance by the man who commissioned it, Viktor’s father, my great-great-grandfather Ignace.

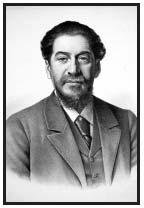

There are, I am afraid, three Ignace Ephrussi in this story, stretching across three generations. The youngest is my great-uncle Iggie in his Tokyo flat. Then there is Charles’s brother, the duelling Parisian with his string of love-affairs. And here in Vienna we meet the Baron Ignace von Ephrussi, holder of the Iron Cross Third Class, ennobled for his services to the Emperor, Imperial Counsellor, Chevalier of the Order of St Olaf, Honorary Consul to the King of Sweden and Norway, Holder of the Bessarabian Order of the Fleece, Holder of the Russian Order of the Laurel.

Baron Ignace von Ephrussi, 1871

Ignace was the second-richest banker in Vienna, owning another huge building on the Ringstrasse and a block of buildings for the bank. And that was just in Vienna. I find an audit which notes that in 1899 he had assets in the city of 3,308,319 florins, roughly the current equivalent of $200 million; 70 per cent of this wealth was in stocks, 23 per cent in property, 5 per cent in works of art and jewellery and 2 per cent in gold. That is a lot of gold, I think, as well as a splendidly Ruritarian list of titles. You would need a façade with extra caryatids and gilding, if you had to live up to that list.

Ignace was a

Gründer

, a founding father, of the

Gründerzeit,

the founding age of Austrian modernity. He had come to Vienna with his parents and older brother Léon from Odessa. When the Danube flooded Vienna catastrophically in 1862, water lapping the altar steps of St Stephen’s Cathedral, it was the Ephrussi family who loaned money to the government for the construction of embankments and new bridges.

I own a drawing of Ignace. He must be about fifty, and he is wearing a rather beautiful jacket with wide lapels and a fatly knotted tie with a pearl stuck through it. Bearded, with his dark hair swept back from his brow, Ignace is looking straight back at me appraisingly and his mouth is set for judgement.

I have a portrait of his wife Émilie too, grey-eyed with a rope of pearls spun round and round her neck and sweeping down over a black shot-silk dress. She is also pretty judgemental, and every time I’ve hung this painting at home I’ve had to take it down, as she looks down on our domestic life in disbelief. Émilie was known in the family as ‘the crocodile’, with a most engaging smile – whenever she smiled. As Ignace had affairs with both of her sisters, as well as keeping a series of mistresses, I feel lucky that she is smiling at all.

Somehow I imagine that it was Ignace who chose Hansen as architect; he understood how to make symbols work. What this rich Jewish banker wanted was a building to dramatise the ascendancy of his family, a house to sit alongside all these great institutions on the Ringstrasse.

The contract between the two men was signed on 12th May 1869, with building permission granted by the city at the end of August. By the time he came to work on the Palais Ephrussi, Theophilus Hansen had been raised to the nobility; he was now Theophil Freiherr von Hansen, and his client – now knighted – was Ignace Ritter von Ephrussi. Ignace and Hansen started by disagreeing about the scale of the elevation: the plans record endless revisions as these two strong-willed men worked out how to use the spectacular site. Ignace demanded stables for four horses as well as a coach-house ‘for two to three carriages’. His chief requirement was for a staircase just for himself, one that couldn’t be used by anyone else living in the house. It is all spelt out in an article from 1871 in the architectural journal

Allgemeine Bauzeitung

, illustrated with splendid plans and elevations. The Palais would be a grandstand onto Vienna: its balconies would overlook the city, and the city would pass by its huge oak doors.

I stand outside. This is the last moment when I can choose to turn away, cross the road, take the tram and leave this dynastic house and story alone. I breathe in. I push the left door, cut into the huge oak double gates, and am in a long, high, dark corridor, a gold coffered ceiling above me. I go on and I am in a glazed courtyard five storeys high, with internal balconies punctuating the huge space. There is a life-size statue of a rather muscle-bound Apollo half-heartedly strumming his lyre in front of me, held on his pedestal.

There are some small trees in planters and a reception desk, and I explain, poorly, who I am and that this is my family house, and that I would love to look around if it is not too much of a problem. It is certainly not a problem. A charming man emerges and asks me what I would like to see.

All I can see is marble: there is lots of marble. This doesn’t say enough. Everything is marble. Floor, stairs, walls of staircase, columns on staircase, ceiling over staircase, mouldings on ceiling of staircase. Turn left and I go up the family stairs, shallow marble steps. Turn right and I go into another entrance hall. I look down and the patriarch’s initials are set in the marble floor: JE (for Joachim Ephrussi) with a coronet above them. By the grand stairs are two torchères, taller than me. The steps go on and on, trippingly shallow. Black marble frames to the huge double doors – black and gold – I push, and I enter the world of Ignace Ephrussi.

For rooms covered in gold, it is very, very dark. The walls are divided into panels, each delineated by ribbons of gilding. The fire-places are massive events of marble. The floors are intricate parquet. All the ceilings are divided into networks of lozenges and ovals and triangular panels by heavy gilded mouldings, raised and coffered into intricate scrolls of neoclassical froth. Wreaths and acanthus top the heady mixture. All the panels are painted by Christian Griepenkerl, the acclaimed decorator of the ceilings of the auditorium of the Opera. Each room takes a classical theme: in the billiard-room we have a series of Zeus’s conquests – Leda, Antiope, Danaë and Europa – each undraped girl held up by putti and velvet draping. The music-room has allegories of the muses; in the salon, miscellaneous goddesses sprinkle flowers; the smaller salon has random putti. The dining-room, achingly obvious, has nymphs pouring wine, draped with grapes or slung with game. There are more putti, for no good reason, sitting on doorway lintels.

Everything in this place, I realise, is very shiny. There is nothing to grip onto with these marbled surfaces. Its lack of tactility makes me panic: I run my hands along the walls and they feel slightly clammy. I thought I’d worked through my feelings about Belle Époque architecture in Paris, craning my neck to see the Baudrys on the ceilings of the Opéra. But here it is all so much closer, so much more personal. This is aggressively golden, aggressively lacking in purchase. What was Ignace trying to do? Smother his critics?

In the ballroom, with its three great windows looking across the square to the Votivkirche, Ignace suddenly lets something slip. Here, on the ceiling – where in other Ringstrasse

Palais

you might find something Elysian – there is a series of paintings of stories from the biblical Book of Esther: Esther crowned as Queen of Israel, kneeling in front of the Chief Priest in his rabbinical robes, being blessed, with her servants kneeling behind her. And then there is the destruction of the sons of Hamam, the enemy of the Jews, by Jewish soldiers.

It is beautifully done. It is a long-lasting, covert way of staking a claim for who you are. The ballroom is the only place in a Jewish household – however grand, and however rich you might be – that your Gentile neighbours would ever see socially. This is the only Jewish painting on the whole of the Ringstrasse. Here on Zionstrasse is a little bit of Zion.

This implacably marble

Palais

is where Ignace’s three children were brought up. In the cache of family photographs that my father gave me is a salon picture of these children, caught stiffly between velvet drapes and a potted palm. Stefan is the eldest son, handsome and rather anxious. He is spending his days at the office with his father, learning grain. Anna is long-faced and huge-eyed, with massed curls, and looks utterly bored, her picture album almost falling out of her hands. She is fifteen and, apart from dancing lessons, spends her days in a carriage going between at-homes with her glacial mother. And my great-grandfather is the young Viktor. He is called by his father’s Russian nickname, Tascha, and is in a velvet suit, clutching a velvet hat and a cane. He has black, glossy, waved hair and looks as if he has been promised a reward for spending this long afternoon away from his schoolroom, under all these heavy drapes.

Viktor’s schoolroom has a window looking out towards the building site where they were finishing the university, with its rational series of columns telling the Viennese that knowledge is secular and new. For years every window in this new family house on the Ringstrasse looked out onto dust and demolition. And while Charles talks to Mme Lemaire about Bizet in the salons of Paris, Viktor sits in this schoolroom in the Palais Ephrussi with his German tutor, the Prussian Herr Wessel. Herr Wessel made Viktor translate passages of Edward Gibbon’s

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

from English into German, taught him how history worked from the great German historian Leopold von Ranke, ‘

wie es eigentlich gewesen ist

’ – history as it actually happened. History was happening now, Viktor was told; history is rolling like wind through fields of wheat onwards from Herodotus, Cicero, Pliny and Tacitus through one empire to another, to Austria-Hungary and on towards Bismarck and the new Germany.

To understand history, taught Herr Wessel, you must also know Ovid and you must know Virgil. You must know how heroes encounter exile and defeat and return. So after history lessons, Viktor must learn parts of the

Aeneid

by heart. And after this, as recreation I suppose, Herr Wessel teaches Viktor about Goethe, Schiller and von Humboldt. Viktor learns that to love Germany is to love the Enlightenment. And German means emancipation from backwardness, it means

Bildung

, culture, knowledge, the journey towards experience.

Bildung,

it is implied, is in the journey from speaking Russian to speaking German, from Odessa to the Ringstrasse, from grain-trading to Schiller-reading. Viktor starts to buy his own books.

Viktor, it is understood in the family, is the bright one and must get this kind of education. Viktor, like Charles, is the spare son and will not have to be the banker. Stefan is being groomed for this, just like Léon’s eldest son Jules. In a photograph of Viktor a few years later, he is just twenty-two and looks like a good Jewish scholar with his neatly trimmed beard, already slightly plumper than he should be, a high white collar and a black jacket. He has the Ephrussi nose, of course, but what is most noticeable are his pince-nez, the mark of a young man who wants to become a historian. Indeed, in ‘his’ café, Viktor is able to discourse at length, as his tutor has taught him, on this moment in time and how the forces of reaction must be seen in the context of progress. And so on.

Every young man has his own café, and each is subtly different. Viktor’s was the Griensteidl, at the Palais Herberstein close to the Hofburg. This was a meeting place for young writers, the Jung-Wien of the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and the playwright Arthur Schnitzler. The poet Peter Altenberg had his post delivered to his table. There were mountains of newspapers and a complete run of

Meyers Konversations-Lexicon

, Germany’s answer to the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

, to provoke or answer arguments or fuel journalistic copy. You could spend your whole day here, nursing a single cup of coffee under the high vaulted ceilings, writing, not-writing, reading the morning newspaper – the

Neue Freie Presse

– while waiting for the afternoon edition. Theodor Herzl, the paper’s Paris correspondent with his apartment in the rue de Monceau, used to write here and argue his absurd idea of a Jewish state. Even the waiters were rumoured to join in the conversations around the huge circular tables. It was, in a memorable phrase of the satirist Karl Kraus, ‘an experimental station for the end of the world’.

In a café you could adopt an attitude of melancholic separation. This was an attitude shared by many of Viktor’s friends, the sons of other wealthy Jewish bankers and industrialists, other members of the generation that had grown up in the marble

Palais

of the Ringstrasse. Their fathers had financed cities and railways, made fortunes, moved their families across continents. It was so difficult to live up to the

Gründer

that the most one could be expected to do was talk.

These sons had a common anxiety about their futures, lives set out in front of them on dynastic tram-lines, family expectations driving them forward. It meant a life lived under the gilded ceilings of their parents’ homes, marriage to a financier’s daughter, endless dances, years in business unspooling in front of them. It meant

Ringstrassenstil –

Ringstrasse-style – pomposity, over-confidence, the parvenu. It meant billiards in the billiard-room with your father’s friends after dinner, a life immured in marble, watched over by putti.

These young men were seen as either Jewish or Viennese. It doesn’t matter that they may have been born in the city: Jews had an unfair advantage over the

natural-born Viennese,

who had gifted liberty to these Semitic newcomers. As the English writer Henry Wickham Steed said, this was:

Liberty for the clever, quick-witted, indefatigable Jew to prey upon a public and a political world totally unfit for defence against or competition with him. Fresh from Talmud and synagogue, and consequently trained to conjure with the law and skilled in intrigue, the invading Semite arrived from Galicia or Hungary and carried everything before him. Unknown and therefore unchecked by public opinion, without any ‘stake in the country’ and therefore reckless, he sought only to gratify his insatiable appetite for wealth and power…

The Jews’ insatiability was a common theme. They simply did not know their limits. Anti-Semitism was part of common day-today life. The flavour of Viennese anti-Semitism was different from Parisian anti-Semitism. In both places it happened both overtly and covertly. But in Vienna you could expect to have your hat knocked off your head on the Ringstrasse for looking Jewish (Schnitzler’s Ehrenberg in

The Way into the Open

, Freud’s father in

The Interpretation of Dreams

), be abused as a dirty Jew for opening a window in a train carriage (Freud), be snubbed at a meeting of a charity committee (Émilie Ephrussi), have your lectures at the university disrupted by cries of ‘

Juden hinaus!

’ – ‘Jews out!’ – until every Jewish student had picked up his books and left.

Abuse also came in more generalised ways. You could read the latest pronouncements by Vienna’s own version of Édouard Drumont in Paris, Georg von Schönerer, or hear his thuggish demonstrations churning their way along the Ring under your window. Schönerer came to prominence as the founder of the Austrian Reform Meeting, declaiming against ‘the Jew, the sucking vampire…that knocks…at the narrow-windowed house of the German farmer and craftsman’. He promised in the Reichsrat that if his movement did not succeed now, ‘the avengers will arise from our bones’ and ‘to the terror of the Semitic oppressors and their hangers-on’ make good the principle ‘“An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”’. Retribution against the injustices of the Jews – successful and affluent – was especially popular with artisans and students.

Vienna University was a particular hotbed of nationalism and anti-Semitism, with the

Burschenschaften

or student fraternities leading the way with their avowal of kicking the Jews out of the university. This is one of the reasons why many Jewish students considered it necessary to become exceptionally expert and dangerous fencers. In alarm, these fraternities instituted the Waidhofen principle, which meant there could be no duelling with Jews, that Jews had no honour and should not be expected to live as if they did: ‘It is impossible to insult a Jew; a Jew cannot therefore demand satisfaction for any suffered insult.’ You could still beat them up, of course.

It was Dr Karl Lueger, the founder of the Christian Social Party, with his amiability and Viennese patois, his followers with their white carnations in their buttonholes, who seemed even more dangerous. His anti-Semitism seemed more carefully considered, less overtly rabble-rousing. Lueger made his play as an anti-Semite by necessity rather than conviction: ‘wolves, panthers, and tigers are human compared to these beasts of prey in human form…We object to the old Christian Austrian Empire being replaced by a new Jewish Empire. It is not hatred for the individual, not hatred for the poor, the small Jew. No gentlemen, we do not hate anything but the oppressive big cap ital which is in the hands of the Jews.’ It was

Bankjuden

– the Rothschilds and Ephrussi – who had to be put in their place.

Lueger gained huge popularity and was finally appointed mayor in 1897, noting with some satisfaction that ‘Jew-baiting is an excellent means of propaganda and getting ahead in politics’. Lueger then reached an accommodation with those Jews he had assailed in his rise to power, remarking smugly that ‘Who is a Jew is something I determine.’ There was still considerable Jewish anxiety: ‘Can it be considered appropriate for the good name and interests that Vienna be the only great city in the world administered by an anti-semitic agitator?’ Though there was no anti-Semitic legislation, the penalty of Lueger’s twenty years of rhetoric was a legitimisation of bias.

In 1899, the year that the netsuke arrived in Vienna, it was possible for a deputy in the Reichsrat to make speeches calling for

Schussgelder

– bounties – for shooting Jews. In Vienna the most outrageous statements were met with a feeling from the assimilated Jews that it was probably best not to make too much fuss.

It looks as if I am going to spend another winter reading about anti-Semitism.

It was the Emperor who held out against this agitation. ‘I will tolerate no

Judenhetze

in my Empire,’ he said. ‘I am fully persuaded of the fidelity and loyalty of the Israelites and they can always count on my protection.’ Adolf Jellinek, the most famous Jewish preacher of the time, pronounced that ‘The Jews are thoroughly dynastical, loyalist, Austrian. The Double Eagle is for them a symbol of redemption and the Austrian colours adorn the banners of their freedom.’

Young Jewish men in their cafés had a slightly different view. They were living in Austria, part of a dynastic empire, part of a stifling bureaucracy where every decision was endlessly deferred, where everything aspired to be ‘

kaiserlich-königlich

’,

k & k

, imperial and royal. You could not move in Vienna without seeing the double-headed Hapsburg eagle or the portraits of the Emperor Franz Josef, with his moustaches and sideburns and his chest of medals, and his grandpaternal eyes following you from the window of the shop where you bought your cigars, over the little desk of the maître d’ in the restaurant. You could not move in Vienna if you were young, wealthy and Jewish, without being observed by a member of your extended dynastic family. Anything you did might end up in a satirical magazine. Vienna was full of gossips, caricaturists – and cousins.

The nature of the age was much discussed around these marble café tables and between these earnest young men. Hofmannsthal, the son of a Jewish financier, argued that the nature of the age ‘is multiplicity and indeterminacy’. It can rest only, he said, on ‘

das Gleitende

’, moving, slipping, sliding: ‘what other generations believed to be firm is in fact

das Gleitende

’. The nature of the age was change itself, something to be reflected in the partial and fragmentary, the melancholy and lyric, not in the grand, firm, operatic chords of the

Gründerzeit

and the Ringstrasse. ‘Security,’ said Schnitzler, the well-off son of a Jewish professor of laryngology, ‘exists nowhere.’

Melancholy fits with the perpetual dying fall of Schubert’s

Abschied,

‘Farewell’.

Liebestod

, the love of death, was one response. Suicide was terribly common among Viktor’s acquaintances. Schnitzler’s daughter, Hofmannsthal’s son, three of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s brothers and Gustav Mahler’s brother would all kill themselves. Death was a way of separating oneself from the mundane, from the snobbery and the intrigues and the gossip, drifting into

das Gleitende

. Schnitzler’s list of reasons for shooting yourself in

The Road into the Open

encompasses ‘Grace, or debts, from boredom with life, or purely out of affectation’. When, on 30th January 1889 the Crown Prince, Archduke Rudolf, committed suicide after murdering his young mistress Marie Vestera, suicide gained its imperial imprimatur.

It was understood that none of the sensible Ephrussi children would go as far as that. Melancholy had its place. A café. It shouldn’t be brought home.

But other things were brought home.

On 25th June 1889 Viktor’s sister, the long-faced,

belle laide

Anna, converted to Catholicism in order to marry Baron Herz von Hertenreid. She has a long list of possible husbands, and now she has found a banker and a baron who comes from the right kind of family, even if he is Christian. The Herz von Hertenreids are a family that – approving tones from my grandmother –

always spoke French

. Conversion was relatively common. I spend a day looking up the records of the Viennese Rabbinate in the archives of the Jewish community next to the synagogue in Judengasse, the names of every Jew born, married or buried in Vienna. I’m searching for her when an archivist turns. ‘I remember her marriage,’ she says, ‘1889. She has the firmest signature, confident. It almost goes through the paper.’