The Heart Has Reasons (21 page)

Once, though, when I

was

home, my mother and I took in an onderduiker ourselves—a man who came to us at the time of the Railway Strike. You see, in 1944 the Germans started to plunder Holland on a much larger scale, and they began to completely dismantle Dutch industry. I remember seeing train after train loaded with all kinds of machinery pass through Bussum on its way to Germany. They stole tens of thousands of electric motors, metal-working machines, oil refinery equipment, and other spoils. Our government-in-exile, based in London, wanted to put a stop to it, and in September they asked the Dutch railway workers to strike, which they did. They also hoped that stopping the trains would assist the Allied forces in their bold plan to seize five bridgeheads across the great rivers, including the furthermost one at Arnhem.

Well, the landing in Arnhem was a failure, “one bridge too far,” as they say, and the strike didn’t stop the pillaging either. Participation was punishable by death, so now you had 30,000 railway workers whose lives were in danger. The Germans started operating the trains themselves, and the worst consequence was that they stopped transporting food supplies west. That began a period of widespread famine.

There was a raid on our little village of Bussum in autumn of ’44, and a section of the town was closed off. But a man came bicycling down our street trying to escape. He rode up to me, panting, “I’m a railway man, and they’ll shoot me if they find me.” I said, “Come with me.” My father and I had dug out a makeshift hiding place beneath the floorboards in the hallway off of our kitchen. There was a big cupboard there, and you had to go through the lower door of the cupboard to

get down below. We had sawed the floorboards, so they could be lifted up at that spot.

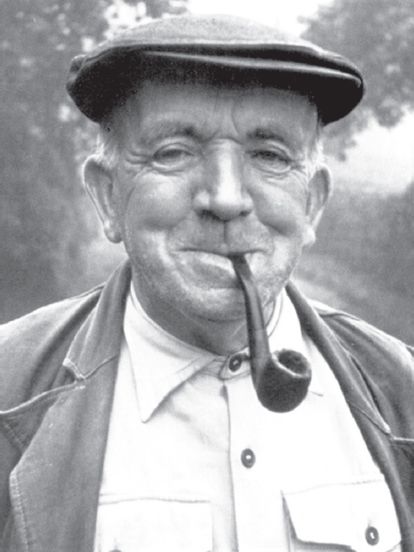

Kees (center) on one of his many bicycle trips during the war.

When we heard the Germans approaching, we opened the cupboard, pulled up the floorboards, and crawled under. Then my mother put the boards back, threw a piece of linoleum over them, and put the vacuum cleaner on top of it all. A few slivers of light came through the slats, but besides that, it was pitch dark. That railway man and I lay beside each other on the clammy ground, listening to the sounds from the street; we could hear German soldiers yelling, and every now and then, a burst of machine gun fire.

Soon the Nazis were at our house, banging on the door with the butts of their rifles. My mother let them in—six or seven soldiers. At that moment, she remembered that there were some Dutch resistance newspapers on the dining room table—stupid, for we never left those lying around. The Germans were about to search the house, but my mother said, “Here, let me make you something hot to drink.” So she crumpled the illegal papers and lit the wood stove with them. We had no gas anymore, so that was perfectly plausible. Oh, she was clever, and not afraid! Meanwhile, we were lying under there with nothing between us and the jackboots of the Nazis but the floorboards. We listened as the commander questioned my mother.

“Where is your husband?”

“He’s been taken already.”

“And your son?”

“He’s away in the hinterlands.”

“There must be a man in the house, for there is a man’s bicycle on the porch.”

They fired at the ceiling, hoping to scare anybody who was hiding into coming out. Then they went stomping through the house. When they flung open the door to the cupboard, we held our breath—but they had no idea it was the entrance to a hiding place. And then my mother started talking about our dog: we had a beautiful husky, a dog from Canada, and she said, “Have you ever seen a dog like this? Isn’t he a handsome dog?” and they said, “Yah, yah, he sure is.” The Nazis loved dogs, so she was able to divert their attention that way. Just then I heard a thumping sound—which startled me terribly until I realized that it was just the dog’s tail beating against the floorboards, something he always did when he was petted.

All the while, that railway man’s heart was pounding like a hammer in his chest—boom, boom, boom. Could they hear it? Thankfully, no. But I must say, my mother was very brave, don’t you think? I do believe that she liked to outsmart them—and she did.

Six months before the war ended we had the “hunger winter”—oh, that was a wretched time, just trying to get enough food to fill your stomach. By November 1944, there was hardly any food left. I remember my mother dividing what little food there was between us, and I had the cheek to say something like, “I think father has more.” And then we’d compare our portions again and again. It was all in good humor, but you can’t imagine how little we had to get by on in those days.

In Amsterdam, people were starving. Those who were able traveled into the country with handcarts, wheelbarrows, or old bicycles. They would bring their linen, towels, and tablecloths to barter for food. In the beginning they had success, but after a while the farmers had enough of those things and started to make greater and greater demands. There was a farmer named Derk JanVeldhuis who was so ashamed that his fellow farmers might ask for a golden wedding ring in exchange for food that he gave away his entire potato crop—anyone who was hungry could get ten kilos of potatoes.

On one of my bicycle trips into the north country, I passed by the

village of Bunschoten where there was a big dairy. That was a very Christian place, and anyone passing by could stop there and have some free soup. Thin soup, just some potatoes and cabbage, but it was hot, and eased the ache in your belly. I stopped there to get my fill, and noticed a young boy, I think about eleven or twelve, sitting there crying his eyes out. Well, there was always something unhappy going on, so I didn’t pay much attention. But after I had eaten my fill and rested my bones a little, I went up to him to find out what was the matter.

Kees’ friend Derk, who gave away his entire potato crop to feed

the hungry.

He told me that his father was doing hard labor in Germany, and that his mother had sent him from Amsterdam to bring back food for her and his two little sisters. She had given him some towels, linen, and a fine tablecloth to barter. He had met a farmer who must have pitied him, for he had given him two pounds of butter—very precious in those days; on the black market it was selling for a hundred times the normal price—and wheat, and oatmeal, and some other things as well. He slept at that farmer’s place, and the following morning, when he was traveling back with his two full bags of food, he passed by this dairy and stopped to have some soup. And there he met a woman who said, “If you’ll watch my bicycle while I go to eat, then I’ll do the same for you.” So he guarded her bicycle while she went in and had some soup, and when it was his turn, he went in. But when he returned, all his things were gone.

I thought, “This is the limit. This is the absolute limit. He’ll never get over it.” So I went to the manager of this big dairy and I said, “Look here what I’ve seen just now.” He said, “Don’t start—all day long I hear nothing but terrible stories and everybody tries to convince me that their story is the worst.” “Yes,” I said, “but in this case you

must

help.” So I told him what had happened, and he was a very good Christian, that man,

but he was swearing—“Godverdomme!” But in the end he gave him butter again, yeh, yeh, and other things as well, and I said to the boy, “Now you go straight home, don’t talk to anyone, and try not to stop until you’ve made it home.” Yah, but you have to wonder, what went on in the mind of that woman? Perhaps she had very hungry children at home, and she looked into his bag and saw all that food. Still, she should have been more—well, I don’t know what.

I think more people would have helped the Jews had they truly known what was being done to them. Moreover, many people were afraid, and I can understand. The Germans controlled the radio, and were always broadcasting messages telling people how foolish it was to try to do anything against them. Every couple weeks death notices would appear: “The German Army announces the death of twenty people, shot for engaging in illegal practices.” Then they would list their names.

Once, early in the war, I remember talking with Ger Weevers, one of my friends from that nature group, and he asked, “What do you think we can do against the Germans?” I said, “Not very much.” He said, “Come visit me in Zwolle, and we’ll talk about it.” So the next week I took a train to Zwolle, and as soon as I got off, I saw one of those notices and the first name on the list was Ger Weevers. I said to myself, “That can’t be. I just talked to him last week.” I started to walk away, but I went back again to stare at it: yes, there was his name: “Ger Weevers, shot while trying to escape.” I walked away again, and then turned around—I went back three times to stare at that notice. So I turned around and went back home and, indeed, I never saw him again. Even now, I get chills thinking about it. He was no older than me.

Yah, so people were afraid. Still, I came across many people who were willing to help the Jews—often the most simple, humble people. Just an ordinary bridge watcher—a man who would raise and lower the bridge for boats—he would say, “Well, yes, if that’s the problem, I think we must do something.” The people who were high up the social ladder were much less willing to get involved. Perhaps they were better able to see the consequences, I don’t know.

I once came to the aid of a Dutch girl who was being accosted by a few laborers. I took her part, protected her, freed her. And it so happened that her father, Mr. van Eijk, was the head of a big Protestant publishing firm. He wrote me a long letter to thank me and said, “If

I can do anything for you, please let me know.” So I thought, well, he’s got a big publishing firm, and a printing firm in Nijkerk with about eighty workers. Perhaps he would be reliable, and could recommend people to take in onderduikers. So I wrote him a letter that I would like to visit him.

He invited me to dinner at a time when we had very little food, but, as the director of that big printing firm, he had everything. So I went there and had a meal, and at the beginning of the meal he folded his hands and prayed, “Good Lord,” and he had quite a lot of words, and then he intoned, “And I especially ask your attention for all those people who are being persecuted by the Germans.” I thought, “Well, I’m sitting in roses, oh, that’s good.” And so, after dinner, he took me aside and asked, “What can I do for you?” “Well,” I said, we are looking for people who will take in Jewish children, Jewish boys. . . .” “How dare you ask me that?” he bristled. “I’m the director of a firm with a lot of responsibilities—how dare you ask me that!” So that was quite different from what I expected. There’s theory and there’s practice.

How did you become a person who was willing to help Jewish people?

Well, my father was an idealistic man; he always believed that we could build a better world if we all worked together. He was a leftist, a socialist, and a member of the Labor Party. So I grew up hearing “You are your brother’s keeper,” and “The broadest shoulders carry the heaviest burden.” Well, if that’s what you believe, you must act on it.

Those sound like religious ideals.