The Hidden People of North Korea (26 page)

Read The Hidden People of North Korea Online

Authors: Ralph Hassig,Kongdan Oh

Tags: #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #Asia, #Korea, #World, #Asian

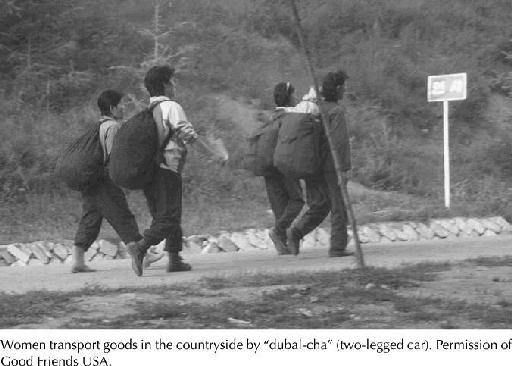

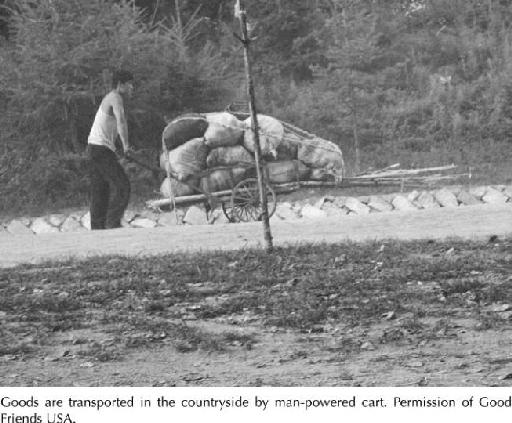

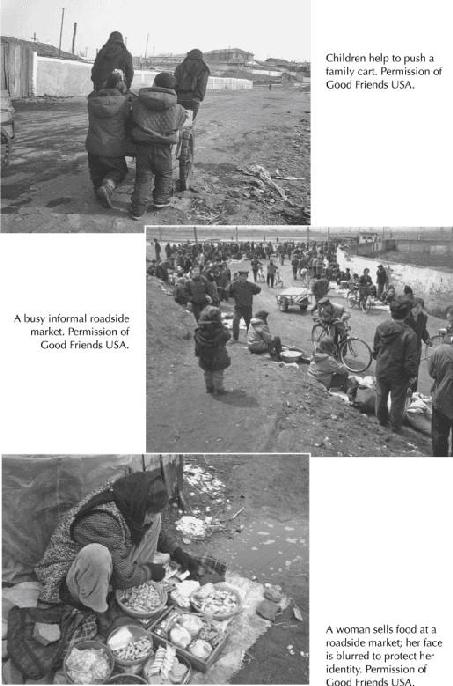

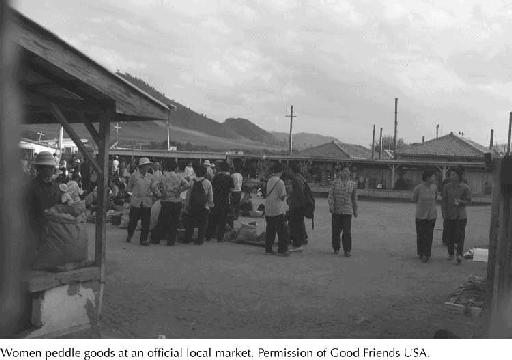

The state continues to intervene in the economic lives of the people by promulgating and sporadically enforcing strict rules for market activity. In the absence of resources to feed the people or any enthusiasm for the market economy, the government and the party exercise a constraining, rather than a facilitating, influence on economic life. Now that the socialist economy has collapsed, the state is trying to raise funds by taxing private economic activities. This taxation is bitterly resented by the people, who feel that they have been abandoned by state socialism and now are being taxed for finding an alternative livelihood.

Rich people are beginning to flaunt their wealth by driving private cars, wearing expensive clothes, and living in apartments and houses they have illegally purchased, although they risk exposing their riches and falling afoul of crusading authorities. The Kim regime intermittently launches campaigns against nonsocialist activities and wealth and sometimes makes an example of these people, but they seem willing to take their chances. Entrepreneurs in China and Russia expose themselves to similar risks.

There is a limit, however, to how much the North Korean economy can change. Deep and enduring economic changes must await political change, and once politics begin to change, people will ask why they had to suffer for so many years and why North Korea has fallen so far behind. People will no longer believe the propaganda claims that “imperialists,” primarily the Americans, are responsible for North Korea’s economic failures. They will begin to ask questions about how Kim and his associates have been running the country, and at that point it will be all over for the Kim family regime.

In food, housing, and health care, the stealthy transition from a command socialist economy to a protocapitalist economy is teaching North Koreans to become entrepreneurs and consumers.

91

The transition is also creating a gap between the very rich and everyone else. Koreans with good political connections, business talent or experience, access to foreign currency, or good luck are beginning to make thousands and tens of thousands of dollars in business. The majority of Koreans only earn enough to buy food and other basic necessities, and some people still die of starvation.

It is difficult to predict North Korea’s economic future. The tension between the growing market economy and the regime’s continuing hostility toward capitalism has resulted in an awkward economic transition. The regime periodically rolls back market initiatives, as it did in May 2004 when it banned the use of cell phones, and then relaxes enforcement of the bans. In 2007, the government tried to prohibit women under the age of fifty (in some places, forty) from selling goods in the markets. According to an October 2007 Korean Workers’ Party document, which quotes Kim Jong-il’s instructions, the major problems with markets are that “women in their prime and workable age” are at the markets rather than at state factories and offices, that merchants are making “exorbitant” profits, and that the sale of South Korean goods is “spreading illusions about the enemy.”

92

The instructions portray markets as instruments of North Korea’s enemies who seek to “employ all vicious means to disintegrate us from within.”

In late 2008, rumors circulated widely that the government had decided to transform the markets into the old-style farmers’ markets that met only three times a month. The order was supposed to go into effect at the beginning of the new year, but nothing happened.

93

If the markets were limited to selling food, it would be a severe blow to North Korean commerce and a hardship on the people. It would also deprive the local officials of the money they earn legally and illegally from running the markets, and for this reason alone, such a move would meet with resistance.

Groups of inspectors are dispatched from Pyongyang to try to stamp out such “antisocialist” activities as viewing smuggled videotapes and using Chinese cell phones along the border. These “secret

gruppa

” (“groups,” from the Russian, which may also be the same as “724 Gruppa” and “No. 5 Anti-Socialist Inspection Groups” mentioned by various defectors) include officials from several security organizations, the party, and the state prosecution, perhaps in order to have personnel from the different organizations keep an eye on each other. The inspection teams are supposed to be on the lookout for activities occurring outside the socialist economy, but since everyone is at least partially engaged in these activities, the inspectors’ efforts are doomed to failure.

The transition from socialism to capitalism seems to have gone too far to stop. The more people turn to the markets, the fewer resources are available to the state—unless it creates a more systematic form of taxing private incomes. People are unable to plan for their future because they cannot know what the economic situation will be from one year to the next, but they can be sure that they must continue to struggle in the new marketplace because the old socialist economy is unlikely to return.