The History Buff's Guide to World War II (10 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

SPEECHES

The Second World War may have been the zenith of the political speech. Never before or since had so much been at stake and the public so affixed upon the voices of their leaders. Never before had so many heard the same words simultaneously, as Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels contended, “I hold radio to be the most modern and most important instrument of mass influence that exists anywhere.” And since the advent of television, never again would sound have the same leverage as image in politics.

26

Of the following presenters, three deserve particular attention for their skills. Franklin D. Roosevelt mastered the radio like no other. Armed with a select circle of exceptional speechwriters and a baritone intonation of absolute refinement, he exuded confidence and was equally capable in a room of a thousand faces or a single microphone. In turning words into works of art, few politicians ever matched the esteemed Winston Churchill. Almost inept at impromptu deliveries, he labored for hours to write out his dissertations, each one an elegant script. In stirring mass rallies, no one ever equaled Adolf Hitler. Followed more for the passion rather than the substance of his messages, Hitler could credit oration as the alpha and omega of his power.

Listed here in chronological order are the most significant speeches uttered by Hitler, Roosevelt, Churchill, and others during the conflict, based on the extent to which each message dictated policy and defined the war itself.

1. “THE ANNIHILATION OF THE JEWISH RACE” (HITLER—JANUARY 30, 1939)

Hitler’s 1925 wandering rant of

Mein Kampf

publicized his deep-seated hatred for “international Jewry” and its supposed destructive effect on German culture. The Third Reich’s anti-Jewish laws, growing in number and ferocity since 1935, also demonstrated a political willingness to let harsh rhetoric turn into punishing edicts. But in a Reichstag speech on the sixth anniversary of his ascension to the chancellorship, Hitler spoke of an answer to the “Jewish question” that went beyond repression and deportation.

The long and loud sermon contained the usual contaminants—denunciations of the V

ERSAILLES

T

REATY

, warnings of the “Red plague” of communism, declarations of a desired peace. More than usual, he spoke of the West. He emphasized how Americans, Britons, Dutch, and others were unwilling to take all of Germany’s Jews. He then concluded that a solution to the “problem” was forthcoming.

In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet and have usually been ridiculed for it…If the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the Bolshevization of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!

No document bearing Hitler’s signature has ever surfaced authorizing the extermination of Jews. But his January 30, 1939, speech was the first and most damning indication that he viewed genocide as an acceptable end, if not a justifiable means, to the conduct of war.

27

Hitler went on to use the phrase “annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe” word-for-word in five other public speeches.

2. “I HAVE ALSO REARMED THEM” (HITLER—APRIL 28, 1939)

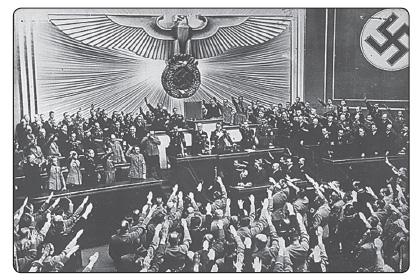

In the uneasy spring of 1940, Franklin Roosevelt sidestepped diplomatic etiquette and bluntly requested Hitler spell out Germany’s foreign policy. Two weeks later der Führer delivered a sober response. Standing before an audience of Reichstag members in the Berlin Kroll Opera House, Hitler gave one of his most credible and coherent summations of his political career. It may have been his best.

The Reichstag was a venue Hitler commanded but held in low esteem. On the other hand, the attendees never failed to show their support for der Führer.

On Britain, Hitler insisted he respected the kingdom but accused it of encircling Germany with hostile alliances, as it allegedly had done in 1914. On Poland, he demanded access to the Baltic port of Danzig: “Danzig is a German city and wishes to belong to Germany.” In light of these “injustices,” he proceeded to cancel Germany’s 1934 nonaggression pact with Poland and his 1935 treaty with Britain assuring German limitations on warship construction.

He finished this virtual war warning by speaking directly to Roosevelt, painting himself as simultaneously victim, savior, and avenger.

I cannot feel myself responsible for the fate of the world, as this world took no interest in the pitiful fate of my own people. I have regarded myself as called upon by Providence to serve my own people alone…I have succeeded in finding useful work once more for the whole of seven million unemployed…Not only have I united the German people politically, but I have also rearmed them.

It was his last major public appearance before the war. For three and a half months he sat, waited, and watched. Poland rejected his demands outright. The United States remained isolationist. Britain and France failed to establish an alliance with Moscow. To Hitler, his speech appeared to have reaped great rewards.

28

Though compelling, Hitler’s response to Roosevelt was also one of the longest of his career, lasting over two hours.

3. “THEIR FINEST HOUR” (CHURCHILL—JUNE 18, 1940)

When France fell to the Germans in June 1940, Britain looked to be next. Recently defeated French Gen. Maxime Weygand predicted: “In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.” Recently elected prime minister, Churchill stood before Parliament to bolster not only Britain but all states threatened or occupied. It was to be one of the most eloquent and passionate orations of his distinguished career.

29

What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization…[I]f we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour.”

Churchill’s magnum opus initially received mixed reviews. Over time it became deeply inspiring and shockingly accurate. He successfully predicted a direct battle with Germany, one to be fought almost exclusively in the air. He also foretold a poor showing from fascist Italy, joking, “There is a general curiosity…to find out whether the Italians are up to the level they were at in the last war or whether they have fallen off at all.” On his prophecies of a war dominated by “perverted science,” he was all too right. That evening, as if to punctuate Churchill’s warnings of battles and technology, more than a hundred German bombers stormed over England and killed nine civilians in Cambridge.

30

Churchill delivered his speech on June 18, 1940, the 125th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo.

4. “I NOW SPEAK FOR FRANCE” (DE GAULLE—JUNE 18, 1940)

On June 17, 1940, France’s undersecretary of state, and until recently a tank brigadier, landed in London and was brought to No. 10 Downing Street. Churchill knew the tall and stern de Gaulle, though few others had ever heard of him. When the middle-ranking Frenchman asked for BBC airtime to broadcast a message of hope, Churchill immediately agreed, as the prime minister was also diligently crafting a speech for that very purpose. Both voices would hit the airwaves the following evening.

Hours after Churchill’s fatherly announcement, the deep and determined voice of de Gaulle commanded his countrymen to keep fighting:

For France is not alone. She is not alone! She is not alone! Behind her is a vast empire, and she can make common cause with the British Empire, which commands the seas and is continuing the struggle. Like England, she can draw unreservedly on the immense industrial resources of the United States…Tomorrow I shall broadcast again from London…I, General de Gaulle, a French soldier and military leader, realize that I now speak for France.

Pure de Gaulle. Churchill had not granted airtime for the following night. Most important, the British had made no indication of recognizing him in any official capacity, nor had the United States, nor for that matter had the French. But de Gaulle’s speech was the first step on a long career of self-proclaimed greatness, and he gradually became the de facto head of France.

Though he kept a small army fighting for the Allies, de Gaulle practically asked for the world in return. Repulsed by the uncooperative giant, Churchill would later say, “The heaviest cross I bear is the Cross of Lorraine.”

31

Due to a lack of equipment, committed instead to Churchill’s “Finest Hour” speech that same day, the BBC made no recording of de Gaulle’s historic proclamation, which angered the Frenchman for the rest of his life.

5. “THE ARSENAL OF DEMOCRACY” (ROOSEVELT—DECEMBER 29, 1940)

By his own measure, Roosevelt’s most significant address between his first inaugural and the declaration of war on Japan was his Arsenal of Democracy speech, delivered as his last “fireside chat” of 1940.

32

Though most of the U.S. population was dead set on staying out of the war, much of Europe and eastern China were under the yoke of foreign occupation. Speaking from the White House to an international radio audience, Roosevelt assured his listeners that the best way to avoid sending troops overseas would be to send weapons instead.

The people of Europe who are defending themselves do not ask where to do their fighting. They ask us for the implements of war, the planes, the tanks, the guns, the freighters which will enable them to fight for their liberty and for our security. Emphatically we must get these weapons to them, get them to them in sufficient volume and quickly enough so that we and our children will be saved the agony and suffering of war which others have had to endure…We must be the great arsenal of democracy…I call upon our people with absolute confidence that our common cause will greatly succeed.

Response to the speech was overwhelming. Cables, calls, and letters poured into the White House, more than Roosevelt had ever received in his career. Nearly every correspondence expressed approval and support. Roosevelt would follow up this triumph by introducing a bill to Congress for a program called L

END

-L

EASE

.

33

Many Londoners who tuned in to Roosevelt’s historic statement had a hard time hearing it. At the time of the broadcast, the British capital was undergoing a sizable Luftwaffe air raid.

6. “WE MUST WAGE A RUTHLESS FIGHT” (STALIN—JULY 3, 1941)

Quivering, stuttering Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov delivered the tragic news via state radio: Nazi Germany had just invaded the Soviet Union. Molotov nervously called for action, but his words were a feeble plea made less convincing by the canned idioms he sputtered: “The government calls upon you, citizens of the Soviet Union, to rally still more closely around our glorious Bolshevist party, around our Soviet Government, around our great leader and comrade, Stalin.”

Stalin ordered Molotov to deliver the speech, as he was either unwilling or unable to do so. Nearly two weeks passed before the Man of Steel brought himself to talk to his people, yet when he did, his words conveyed a new message.

We must wage a ruthless fight against all disorganizers of the rear… All who by their panicmongering and cowardice hinder the work of defense, no matter who they are, must be immediately hauled before a military tribunal…In case of a forced retreat of Red Army units, all rolling stock must be evacuated; to the enemy must not be left a single engine, a single railway car, not a single pound of grain or a gallon of fuel.

Stalin was unveiling a policy of slash and burn. Nothing, including people, would be spared in creating a sea of devastation before the approaching Germans. Listeners were not exactly enthralled, but Stalin softened the blow by appealing to religion, ethnicity, and czarist heroes. It was his first use of Mother Russia imagery, a departure from years of Communist rhetoric. Citizens found hope in the changing language, believing victory would bring new freedoms previously unimaginable. In reality, it was a ploy—and an effective one. Stalin immediately enforced slash-and-burn tactics and speedy executions, making the Soviet Union deadly to invaders and citizens alike.

34