The History Buff's Guide to World War II (8 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

Often viewed as the opposite of any given government, Nazism was more like a mutant combination of theoretical extremes: the far right of militant nationalism, the far left of socialist control of industry, the racial supremacy of fascism, and the end of the individual in communism. The system stayed intact by the same method that held Stalin’s together: state-directed terror. Appropriately, Hitler often credited “will” as the basis of his power. An ethereal term, it summarized perfectly a political system that was based largely on reaction rather than direction.

The name of Hitler’s party exemplified the mishmash of his political thinking. Die Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei means “the National Socialist German Worker’s Party.”

EVENTS IN POLITICS

If the governments of the world stumbled into a global conflict, they also stumbled through it. Leaders rose and fell, enemies became friends, friends became burdens, and agendas mutated. The most consistent trait of international relations was inconsistency. Of the principle political figures in the war, only Joseph Stalin and C

HIANG

K

AI

-S

HEK

remained in power from beginning to end. Half the Axis states eventually joined the Allies. And the Allies did not have a common war aim until 1943.

As illustrated below, few of the war’s major political events were premeditated. Most were reactions to changing military conditions, and many created more problems than they resolved. Listed in chronological order, the following acts and conferences did more than any other to change the political landscape of the war and to demonstrate the tenuous unity within alliances.

1. DESTROYERS-FOR-BASES (SEPTEMBER 2, 1940)

On May 15, 1940, just five days into office, with France collapsing under blitzkrieg by the hour, Winston Churchill sent his first telegram as Britain’s prime minister to Franklin D. Roosevelt. Hardly cordial, Churchill was asking for assistance—quite a bit of assistance.

He asked for a gift of “forty or fifty of your older destroyers,” several hundred of the “latest types of aircraft,” plus antiaircraft guns, steel, and a U.S. military presence in neutral Ireland to dissuade German paratroop drops. Lastly, Churchill stated, “I am looking to you to keep the Japanese quiet in the Pacific.”

5

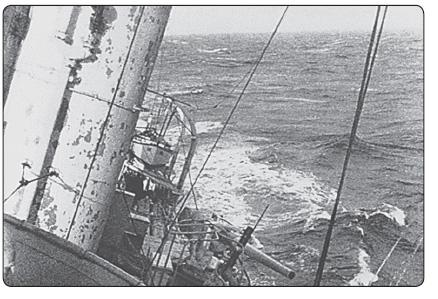

More symbolic than functional, an archaic U S. destroyer lumbers across the Atlantic on its way to the Royal Navy as part of the destroyers-for-bases deal.

Upon receiving these hefty requests, the president was cool but conciliatory. Roosevelt said he would look into the Irish proposal. He reminded Churchill that Britain was free to purchase all the steel and weapons it could afford. As for the Japanese, Roosevelt believed the concentration of U.S. warships at P

EARL

H

ARBOR

was an adequate deterrent.

6

Giving away U.S. destroyers required congressional approval, an unlikely event considering the heavy isolationist sentiment throughout the country. Churchill repeated the request several times in the following weeks, becoming insistent after France fell and Germany suddenly acquired its submarine bases.

In desperation, Churchill offered to lease British naval and air bases in the Caribbean and Newfoundland, free of charge, for ninety-nine years. Roosevelt accepted, as the transaction did not directly violate strict U.S. neutrality laws. The deal was officially settled in September, and English ports began receiving a handful of antiquated sub hunters.

The warships made a marginal difference, but the trade was monumental. The destroyers-for-bases deal was the first measurable step the United States took against twenty years of neutrality and the first successful move by Churchill to tie British and American fates together.

7

The destroyers Britain received were not exactly state of the art. Some of the newest ships were built in 1917.

2. TRIPARTITE PACT (SEPTEMBER 27, 1940)

It seemed like a good idea at the time. For more than a year, Hitler advocated a three-way alliance between Berlin, Rome, and Tokyo. By publicly declaring the unity of the three great military powers, promising to come to each other’s aid if attacked, Hitler believed he could intimidate the United States into staying out of Europe.

The Japanese government, however, was not so confident. One cabinet held over seventy meetings on the issue with no settlement. The navy opposed joining the alliance, as did the emperor, fearing it would anger the United States into war. But when Matsuoka Yosuke became foreign minister, the pact became reality. A brash, eccentric, but charismatic figure, he proclaimed the agreement to be the one and only way to assure peace. “If you stand firm and start hitting back,” he reasoned, “the American will know he is talking to a man.”

8

In response, the United States placed a scrap-metal embargo on “the man,” and public opinion began to equate the empire with the Third Reich. Rather than an irresistible force, the pact became an immovable obstacle to compromise between the United States and Japan.

9

Matsuoka Yosuke had reason to believe he understood Americans. He had lived in the United States for a decade and was a graduate of the University of Oregon.

3. LEND-LEASE (MARCH 11, 1941)

Britain was nearly bankrupt. It was also fighting Germany almost on its own. President Roosevelt struggled to think of a way to help without sending troops overseas, without loaning money, and without doing as Joseph Kennedy Sr., Charles Lindbergh, Robert E. Wood (head of Sears, Roebuck), and others were suggesting—broker a peace with Hitler.

10

Roosevelt came up with an idea while vacationing in the Caribbean, where his destroyers-for-bases trade bore fruit. The United States would provide Britain with the weapons and material required to fight on—guns, warships, transports, tanks—and when the war was over, repayment would be made in kind. While an isolationist Congress was in recess, Roosevelt presented the concept to the American public in his A

RSENAL FOR

D

EMOCRACY

radio address, an act he equated with lending a neighbor a hose when his house was on fire. Response was overwhelmingly in favor, which helped pass the bill despite bitter congressional debates.

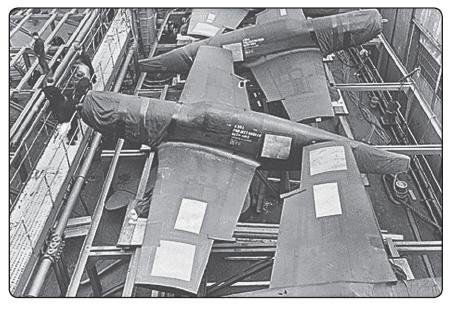

Over the next three years, the United States allocated more than fifty billion dollars in goods and services to forty countries (equivalent to eight hundred billion in 2005 dollars). Britain received nearly half. The Soviet Union, joining the Allies later in 1941, received a quarter of the take, amounting to about 7 percent of what the Soviets produced on their own. Third and fourth in line were Free France and Nationalist China.

U.S. fighter planes are readied for shipment. Lend-Lease provided some forty Allied nations with money and materials for war.

Though boosting American industry to new heights and arguably saving Britain from destruction, Lend-Lease became yet another seed of discontent. Recipients perpetually demanded more, especially Stalin and C

HIANG

K

AI

-S

HEK

. Americans worried they were enabling monarchies and dictatorships to grow even stronger. Harry Truman did little to settle the issue when he shut off the valve the very moment Japan surrendered.

11

Reportedly, upon hearing that the U.S. Congress passed Lend-Lease, Winston Churchill actually danced.

4. ATLANTIC CHARTER (AUGUST 9, 1941)

On a ship off Newfoundland, in their first face-to-face meeting as heads of state, Roosevelt and Churchill negotiated a set of “common principles.” With eight brief points, the document (christened “the Atlantic Charter” by the London press) promoted self-determination, free trade, labor rights, civil rights, freedom of the high seas, and international disarmament. It also condemned border changes by coercion and pledged “the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny.” Issued as a press release, it was intended to be a simple statement of unity against fascism. Others interpreted it as a definitive road map for the postwar world.

Within a month Churchill was backtracking. He assured Parliament that “disarmament” meant Germany and Japan, with the British military remaining dominant far into the postwar period. On self-determination he was most adamant. An ardent imperialist, he emphasized that the provision only applied to Europe, not to British colonies. His hypocrisy was not lost on Burmese, Indians, South Africans, and others living under the Union Jack. Yet the prime minister was quite ready to defend self-determination when Stalin later insisted on maintaining Soviet control over Poland, adding that “President Roosevelt holds this view as strongly as I do.”

12

Yet neither Roosevelt nor Churchill followed the charter closely. Generally repulsed by Britain’s grip on old colonies, Roosevelt was more apt to recognize Soviet dominion over the Poles, the Baltic states, and Ukraine. When asked in 1944 if self-determination no longer applied to Europe, Roosevelt replied that the Atlantic Charter was not a binding treaty but merely a press release, written on “just some scraps of paper.”

13

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill issued the Atlantic Charter after a conference aboard USS

Augusta

at Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, on August 9, 1941.

But in 1941, the charter meant far more in one respect. It was the first publicly declared statement between a belligerent and a neutral that they held the same war aims and were committed to defeating the Third Reich.

The Atlantic Charter would live on after the war as the foundation of the charter of the United Nations.