The History of Florida (36 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 167

proof

Thirteen years after their return, Spanish residents of St. Augustine enjoyed use of a

new Roman Catholic church, larger than any that had stood in the city before. De-

signed by royal engineer-architect Mariano de la Rocque, the coquina stone structure

was erected on the north side of the central plaza during the years 1793–97. Its neoclas-

sic facade was typical of parish and mission churches built elsewhere in the Spanish

Americas during the period. This photograph was taken one hundred years after its

completion.

Forbes reached Pensacola in 1784, shortly after the Spaniards had reached

an agreement with the Creeks to supply them with trade goods. Panton was

a friend of Alexander McGillivray, an influential mixed-blood Upper Creek

chief, and, with McGillivray’s support, Panton, Leslie and Company eventu-

al y secured a large part of the Indian trade.

The company traded English-made goods, especial y guns, powder, and

shot, for deerskins and other furs. It extended credit to the Indians who

were soon heavily in debt—$200,000 or more—to the firm. Panton and

his partners spent years collecting these debts. One thing worked to their

168 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

advantage: The Indians owned large tracts of land which they traded, not

always willingly, to cancel their debts.

Since the United States eagerly wanted Indian lands, the company pres-

sured the Indians in 1805 into trading 8 million acres to the United States.

The land was actual y in U.S. territory. With the cash that they received, the

Indians paid off part of their debts to the company. Later, the Indians and

the Spanish government gave the company 2.7 million acres in West Florida

as recompense for losses sustained by the company during the War of 1812.

Eventual y, and because of a technicality, the United States confirmed only

1.4 million acres of this grant, known as Forbes Grant I. At its peak, Pan-

ton, Leslie and its successor firm, John Forbes & Co., exercised significant

control over the Indians of the Floridas and played an important role in the

history of both East and West Florida during the years 1783 to 1821.

Residents of East Florida participated in the Atlantic-wide economy that

was fed by the mass production of the emerging Industrial Revolution. It

was a period marked by the rise of the British navy and merchant marine

and the lifting of Spanish trade restrictions. East Florida’s reliance on im-

ports probably was in line with the economic activity in surrounding areas

of both the Caribbean and the United States. Foodstuffs from ports in the

United States were the major imported item. Manufactured goods arrived

proof

in East Florida in vessels from England and the United States; wine, sugar,

rum, coffee, and some tablewares were shipped via Cuba. In the early years

of the Second Spanish Period, Florida planters saw planting rice as a way

to riches. Others with fewer resources or less capital looked to timber and

cattle raising for profit. As the nineteenth century arrived, cotton was re-

placing corn, rice, and other staples on East Florida’s acreage. Planter Fran-

cis Fatio claimed that an acre of cotton would yield ten times the profit of

an acre of corn. The departure of money from the province to the United

States to purchase food for slaves in East Florida now engaged in raising

inedible cotton so alarmed Spanish Governor Enrique White in 1800 that

he official y prohibited the planting of cotton and ordered the immediate

sowing of corn.

Even before it acquired the Indian lands in 1805, the United States had

begun its acquisition of Spanish West Florida, a piece at a time. The area

between the 31st parallel and 32°, 28" north was in dispute between Spain

and the United States from 1783 until 1795. Despite the differences between

the first and second Spanish regimes in its Florida territories, the continuing

role of the provinces as adjuncts of a European power meant a close con-

nection with wars in Europe. Spain’s enemies were the Floridas’ enemies,

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 169

whatever the reality within the provinces. By 1795, Spain’s problems in Eu-

rope, and the French Revolution and its consequences, pushed it to resolve

its dispute with the United States. The result was Pinckney’s Treaty, or the

Treaty of 1795, which gave the disputed area, including the Natchez District,

to the United States. The United States had then sovereignty over al the

lands north of 31° to the Great Lakes and from the Appalachian Mountains

to the Mississippi River.

In 1803, the United States purchased Louisiana from France and although

Spain protested, the sale stood. The United States claimed, without any jus-

tification, that the Louisiana Purchase included all lands from the Missis-

sippi River east to the Perdido River, an area that had been part of French

Louisiana prior to 1763. Official y, those lands had been included in British

West Florida from 1763 to 1783 and in Spanish West Florida after that.

In order to confirm its claim to the disputed area, Spain commissioned

a number of persons to write the history of that region. Among those who

contributed was John Forbes, Panton’s successor, who now headed the

Forbes company, but his paper was more concerned with the economic im-

provement of West Florida than with its history. He believed that it could

be developed into one of the best agricultural and commercial colonies in

the Spanish empire, but his recommendations were lost in the international

proof

intrigue of the time.

Unfortunately, conditions did not improve for West Florida, and plots to

acquire the area west of the Perdido River continued until 1810. In Septem-

ber of that year, insurgents took the fort at Baton Rouge, quickly declared

their independence, and created the Republic of West Florida. They adopted

a constitution modeled after that of the United States and elected as their

governor Fulwar Skipwith. Their flag had a white star on a blue field, thus

making West Florida the first lone star republic. By 1812, the United States

had annexed all of the territory between the Perdido and Mississippi Rivers.

The area between the Pearl and Perdido Rivers was made a part of the Mis-

sissippi Territory, while the area west of the Pearl was incorporated into the

State of Louisiana. By 1814, the United States had occupied Mobile and had

built Fort Bowyer on Mobile Point and a lookout post on the Perdido River.

The Spaniards at Pensacola continual y protested such blatant aggression,

but because of the Peninsular War then raging in Europe, they could do little

about it.

The National Assembly (Cortes

)

of Spain enacted a constitution in March

1812, which also became the law of the two Floridas. The Spanish constitution

of 1812 applied to all of Spain’s territories as well to as the mother country.

170 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

News of the constitution reached St. Augustine in August 1812, and in Octo-

ber an official promulgation took place with a military parade and religious

service. Under the provisions of the Spanish constitution, St. Augustine’s

and Pensacola’s voters elected their first city councils (

ayuntamientos

)

.

Cor-

respondence written by Gerónimo Alvarez, first mayor of St. Augustine, and

the minutes book of the Council indicate that Spanish Floridians accepted

their role of civic responsibility with enthusiasm. The St. Augustine City

Council built a monument to commemorate the constitution of 1812 in the

city’s main plaza. The monument stands today. In Pensacola and St. Au-

gustine, the respective city councils and military governors contended over

the lines of authority. On 4 May 1814, Spain’s King Fernando VII rescinded

the constitution, and within a few months the city councils in both Florida

capitals disbanded and authority over local affairs reverted to the military

governors. In September 1820, St. Augustine celebrated the king’s repromul-

gation of the constitution and reinstatement of the city council. The Spanish

constitution continued in effect until the Floridas were transferred to the

United States. Although short-lived in the Floridas, the Spanish constitution

offered rights and privileges similar to those of the U.S. Constitution, and

with more benefits for black citizens.

The War of 1812 reached the Gulf of Mexico in 1814. General Andrew

proof

Jackson, who had just led the U.S. forces to victory in the Creek War, com-

manded the military at Mobile. The British decided to use Pensacola as their

base of operations in the planned attack upon Fort Bowyer, Mobile, and

New Orleans. Their justification was that Great Britain and Spain were allies

in the Peninsular War. More important, if the British succeeded in their Gulf

coast campaign and captured Mobile and New Orleans, it was clear that they

would return those places to Spain. Thus, a British victory would have seri-

ous consequences for the United States. Jackson learned of the British plans

from James Innerarity, a Scottish merchant in Mobile. He had received the

warning from his brother, John, in Pensacola and from a Havana merchant,

Vincent Gray. John Innerarity had also sent a rider to warn the Americans

at Fort Bowyer of the anticipated British attack. Thus, Americans were pre-

pared when the attack began on 15 September 1814. But after the destruction

of one of their warships,

Hermes,

by the fort’s cannon, the British withdrew

and returned to Pensacola. Two months later, Jackson commanded a U.S.

force that attacked Pensacola to drive the British out.

Because the Spaniards were not at war with the United States, they re-

fused to assist the British against the Americans. The British then abandoned

Pensacola, but they took out their anger at the Spaniards by destroying their

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 171

proof

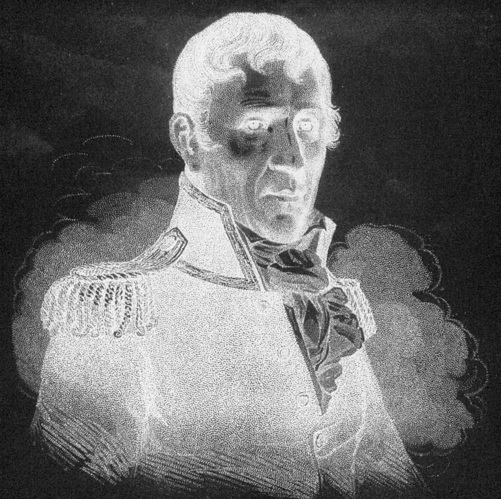

This engraving of Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) was based on a painting for which Jack-

son sat in 1815. Leading Tennessee troops, Jackson made two invasions of the Spanish

Floridas, first during the War of 1812 and again during the First Seminole War of 1818. In

1821, when Florida became a possession of the United States, he returned a third time

to serve a brief stint as military governor. At Pensacola he clashed repeatedly with

the outgoing Spanish governor, José Callava, over change-of-flag details, at one point

clapping the Spaniard in jail. Jacksonville, a site he never visited, is named for him.

Fort San Carlos de Barrancas and the redoubt on Santa Rosa Island before

leaving. The British actively recruited blacks and Indians to assist them in

their efforts to capture New Orleans, which, by December 1814, had become

their main objective. The results of that battle are well known: Once again,

the Americans were victorious. After the Battle of New Orleans, the British

occupied Dauphin Island near Mobile. Determined to win a victory over the

Americans, the British attacked Fort Bowyer on Mobile Point on 9 February

1815. This time they succeeded, but two days after their victory they received

word that the war was over. They quickly abandoned Fort Bowyer and left

172 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

the Gulf coast. This was the last battle of the war of 1812. Fortunately for the

United States, the Stars and Stripes still flew over Fort Bowyer, Mobile, and

New Orleans.

In the years after the Creek War and the War of 1812, some of the Indians

who had fled the Spanish Floridas, the so-called Red Sticks, and their black

allies conducted raids into Alabama and Georgia. In retaliation, the United

States in July 1816 attacked and destroyed Negro Fort, one of their strong-

holds, on the Apalachicola River. But this did not end the problem, and in

March 1818, General Jackson again invaded Spanish West Florida.

Jackson marched to the Suwannee River, where he engaged in a limited

skirmish with the Indians before they slipped away. Although frustrated by