The History of Florida (37 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

this failure, he captured a British soldier of fortune, Robert Chrystie Am-

brister, and learned that the Red Sticks had been forewarned. Jackson then

took the Spanish fort, San Marcos de Apalache, which he suspected of sup-

plying the Red Sticks. He also took prisoner a British merchant, Alexander

Arbuthnot, who was in the fort, and two Red Stick chiefs. Jackson summar-

ily had the chiefs executed and court-martialed the two Englishmen for as-

sisting the Red Sticks in their war against the United States. Both were found

guilty. Ambrister was shot by a firing squad; Arbuthnot was hung from the

yardarm of his own ship,

The

Last

Chance.

Thus, two British subjects had

proof

been tried and executed in Spanish territory by U.S. troops.

After San Marcos, Jackson marched west to Pensacola. He believed the

Spaniards there were still supplying the Indians and encouraging them to

raid nearby Alabama territory. The Spaniards put up a brief defense, but

the main body of troops, led by Colonel José Masot, abandoned the city

and took refuge in the reconstructed Fort San Carlos de Barrancas. Jackson

engaged them, and after a short fight, Masot surrendered. The Spanish of-

ficials and soldiers were put aboard ship and sent to Havana. Pensacola’s

Spanish archives went with them. En route, however, the ship was captured

by corsairs and the records were thrown overboard, consigning much of

Pensacola’s written history to the depths.

For the next nine months, 26 May 1818 to 4 February 1819, Colonel Wil-

liam King, a Jackson appointee, served as the civil and military governor of

Pensacola and West Florida. The Spanish minister in Washington, Luis de

Onís, voiced Spain’s disapproval of the invasion of Spanish territory but ac-

complished little. Final y, the Spaniards returned to Pensacola in February

1819, and Colonel José Cal ava became the last Spanish governor of West

Florida.

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 173

East Florida’s border with the United States offered constant problems as

neither the United States nor East Florida’s colonial government was able

to control border violations, and raids and rustling persisted. U.S. citizens

found the availability of land to be encouragement enough to immigrate,

particularly when, in 1790, the king of Spain invited foreigners to settle in

East Florida by offering homestead grants. Settlers from the southern states

especial y began to move in. The Crown granted each head of a household

100 acres, and each additional family member or slave qualified for an addi-

tional 50 acres. Title to the land passed to the homesteaders after ten years of

occupancy, farming, erecting appropriate buildings, and maintaining live-

stock. Two events tied to the international conflicts, however, were devastat-

ing to the settlement and development of the province. Both were insurgent

military activities fomented in the United States.

In 1793, some residents of Georgia, ostensibly acting on the precepts of

the French Revolution, joined together to take over East Florida militarily

in order to free the Spanish province of what they considered monarchical

tyranny. According to their plan, an expeditionary force would provide sup-

port for Florida residents who might wish to establish an independent re-

public in East Florida and subsequently request annexation into the United

States. Doubtful of the loyalty of residents in the northern part of his prov-

proof

ince in the presence of such a force, Governor Juan Nepomuceno de Que-

sada and his council of war ordered the evacuation of the area between the

St. Marys and St. Johns Rivers during the first week of 1794. To deprive the

invasion of the force of any assistance, the council also demanded that crops

be harvested or destroyed, buildings in the area burned, and residents either

removed to another part of the province or made to leave the colony. These

decisions reflected East Florida’s role as a military outpost, where strate-

gic requirements superseded all other considerations in time of threat. Not

until 9 July 1795, however, did the strike against Spanish sovereignty come,

when Florida residents and compatriots from the United States seized the

Spanish fortification of San Nicolás in present-day downtown Jacksonville.

The rebels persisted in their affiliation with the French cause, identifying

themselves as French forces and cheering for the Republic of France during

the skirmish. But, by mid-October, Spanish troops had routed the insur-

gents from the province, and settlers had relocated in the northern region to

take advantage of newly available lands, abandoned by those who had fled.

The “Patriot War” in East Florida was a conflict that reflected expansion-

ist desires on the part of United States and the anger of slave owners in the

174 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

southern United States over the less-controlled existence of blacks in Span-

ish East Florida. American slave owners wanted especial y to eliminate the

frightening example of African Americans in Florida possessing firearms.

Complicating matters, Amelia Island, the northeasternmost settlement site

in East Florida, had developed since 1807 into an important “neutral” trans-

shipping port for U.S. merchants who wished to bypass their own govern-

ment’s embargo. In 1812, James Madison’s administration supported actions

against Spain’s colony of East Florida in order to expand the jurisdiction of

the U.S. Non-Importation Act, to assert U.S. hegemony in the region, and

to pre-empt any self-serving British activity in Florida.

Crossing into Spanish Florida on 10 March 1812, the Georgian expedi-

tionary force, led by General George Mathews, did not find the anticipated

cooperation from East Florida residents. The invaders took the town and

port of Fernandina on Amelia Island, and by mid-April they were en-

camped at the site of Fort Mose, two miles north of St. Augustine, when

President Madison withdrew official support for the venture in the face of

public disapproval. But the filibusters did not withdraw. That summer, the

Seminole Indians and their African American al ies entered the conflict.

The Patriots turned toward the interior and then occupied lands claimed by

the Seminoles.

proof

Die-hard adherents of the Patriot cause held on in East Florida until May

1814, causing widespread devastation. Various factions burned plantations

and farmsteads on the Florida side of the St. Marys River, both sides of the

St. Johns River, and the estuaries of today’s Intracoastal Waterway as far

south as present-day New Smyrna Beach although they by-passed St. Au-

gustine and left a two-mile swath around the capital unharmed. Livestock

strayed or were consumed by invading troops. John Fraser of Greenfields

Plantation at the mouth of the St. Johns River claimed that he lost $111,000

in property and potential profit from his unplanted cotton crop. Equal y

important to a smaller farmer was the destruction of his houses and barns,

food crops, rifles and miscel any such as a coffee mil , a fiddle and sheet

music, and a fishing net. One rancher never recovered the 800 head of cattle

he owned before the disruptions. Judge Isaac Bronson would declare that

by the time the invaders retired, “the whole inhabited part of the province

was in a state of utter desolation and ruin.”2 The depredation discouraged a

number of settlers who had opted to remain in East Florida after their losses

in 1794, and they departed the province in disgust after the so-called Patriot

War.

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 175

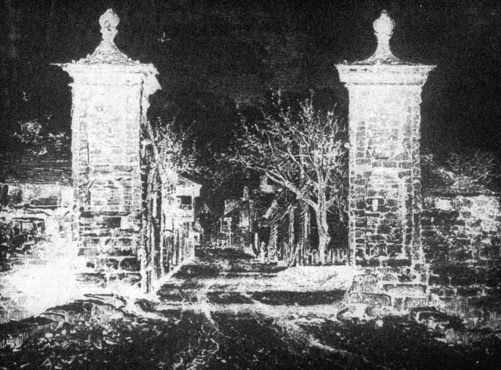

When Spaniards returned to occupy St. Augustine after the twenty-one-year British in-

terregnum, they found the physical appearance of the city substantially unchanged. In

1808, the Spanish Crown built a new, more impressive gate for the north entry through

proof

the wall that protected the capital city. Inside the walled city, wood-plank balconies of

the coquina houses still cast their shadows over the old streets.

East Florida continued to be prey to the designs of invaders. Citizens of

the U.S. southern states favored acquiring Florida as an American posses-

sion in order to eliminate the province as a destination for runaway slaves

and to remove the Seminole presence from the northern region of the col-

ony. The good harbor at the mouth of the St. Marys River at Fernandina

attracted smugglers and adventurers. East Florida’s last colonial governor,

José María Coppinger, endeavored to maintain Spain’s presence with dignity

despite minimal support from his superiors in Cuba and troops who were

inadequate both in number and in character. Coppinger even endured the

experience of smugglers kidnapping his son and holding him ransom for

food and other supplies from St. Augustine.

To encourage the loyalty of the residents in the northern area, Coppinger

wisely instituted a form of local government that allowed some degree of

representative decision making through the election of militia officials

and magistrates, although the practice violated Spanish law. The capture of

176 · Susan Richbourg Parker and William S. Coker

Amelia Island in July 1817 by English-born Gregor MacGregor, a notorious

insurgent, again disrupted peace in the region as well as Coppinger’s suc-

cesses with the citizenry. In December, U.S. soldiers, not Spanish troops,

expelled MacGregor and occupied Amelia Island. In the second half of the

fol owing year, Coppinger readied for another invasion by MacGregor while

residents lived also in fear of troops from the United States.

The incursions of Andrew Jackson into West Florida and Gregor Mac-

Gregor into East Florida mirrored the rebel ions, revolutions, and viola-

tions of sovereign territories in the Americas and as well as in Spain, where

French troops held areas of Spain itself. Spain’s financial state was terri-

ble. The Peninsular War had drained the country of much of its resources.

Spain’s King Fernando VII played politics with his countrymen and with the

French. On top of that, rebellion was rampant in the Americas and soldiers

revolted in Spain itself. Meanwhile, to no one’s surprise, U.S. Secretary of

State John Quincy Adams and Luis de Onís were negotiating for the transfer

of the Floridas to the United States.

On 22 February 1819, the often discussed treaty ceding the Floridas to

the United States was final y negotiated and signed in Washington by Ad-

ams and Onís. The Spanish Crown vacil ated on affirming the treaty, and

the United States threatened instead to take East Florida forcibly in 1820.

proof

Among the items in dispute were new, large land grants to Spanish nobles,

which would eliminate the acreage from the public domain under Ameri-

can rule and make the parcels either unavailable for settlement or unaccept-

ably expensive.

On 22 February 1821, the treaty of cession was final y ratified by both

countries. According to its terms, the United States assumed $5 mil ion

worth of Spanish debts to American citizens and surrendered any claims

to Texas. Governor Coppinger urged East Florida residents to emigrate to

Cuba, Texas, or Mexico. He received instructions to encourage the reloca-

tion of the Seminoles to the U.S.-Texas border, where they could serve as

a valuable and strategic buffer to America penetration of Texas. On 10 July

1821, at 5:00 a.m., the Spanish flag was raised at St. Augustine for the last

time. By 6:00 p.m., the last remaining Spanish soldier had departed from the

city to the vessels waiting to take Spanish subjects to new posts and homes.

A formal transfer of flags took place at Pensacola on 17 July.

More than three centuries of sunrises and sunsets lay between the first

and final appearances of the Spanish flag in Florida. It will be the twenty-

second century before the same can be said about the flag of the United

States.

The Second Spanish Period in the Two Floridas · 177

Notes

1. Weber,

Spanish

Frontier

, 336.