The History of Florida (84 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

during the Mexican War (1846–48). By 1859, the yard had constructed USS

Pensacola

and USS

Seminole

; however, limited facilities prevented large-

scale construction of steam-driven vessels, and shipbuilding fel into de-

cline. The yard and nearby forts soon had different roles to play as the Civil

War split control of the instal ations. Fort Pickens remained in Union hands

and the others became Confederate strongholds.

Civil War

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Union implemented a three-pronged

offensive known as the Anaconda Plan. It called for taking the Confederate

capital at Richmond, blockading southern coasts, and controlling the Mis-

sissippi River. While Florida played no part in the taking of Richmond, the

state became a vital component in the Union’s blockade and inland river

400 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

campaigns. For the South, Florida remained an area ripe for blockade-run-

ners, and it was a necessary buffer to maintain inland supplies. Blockade-

runners operated out of several ports, especial y those with interior rail-

road access such as Pensacola, Jacksonville, Apalachicola, and St. Marks. To

maintain the blockade, the Union captured ports such as Jacksonville, Fer-

nandina, and St. Augustine in the early months of the war, while Fort Taylor

in Key West and Fort Pickens in Pensacola never fell to the Confederacy.

The blockade consisted of four squadrons, with three of those squad-

rons relying on Florida ports and coastlines for fuel and supplies. Key West

was headquarters for the East Gulf Blockading Squadron, whose territory

stretched from St. Andrews Bay, about 100 miles east of Pensacola, down

the peninsula and halfway up the Atlantic coast to approximately Cape Ca-

naveral. Due to the region’s isolation from the rest of Confederacy, the East

Coast Squadron dealt mainly with stopping blockade-runners and with de-

stroying the coastal saltworks necessary for preserving the South’s meat. The

East Gulf Squadron also patrolled farther south to Spanish-controlled Cuba

and east to the Bahamas. Although the East Gulf Squadron captured several

blockade runners and seized Confederate property, it did not play a major

role in the overall Union strategy to “strangle” the South. The squadron had

too few vessels to block major ports and remained a forgotten post for most

proof

of the war.

Rather, Union efforts in Florida turned to areas closest to other southern

states. The Atlantic and the West Gulf Coast Squadrons picked up where the

East Coast Squadron left off. The West Coast Squadron, under command

of Admiral David Farragut, focused its efforts on taking the Mississippi

River and on preventing blockade-runners from supplying New Orleans.

Although emphasis had shifted farther west, Commander David Porter

used his mortar flotil a to bombard Mobile. While he failed to accomplish

much within Mobile Bay, his actions propel ed Confederates to abandon

Pensacola. With Union efforts concentrated on the Mississippi River, the

blockade along ports such as Mobile remained porous and numerous south-

ern vessels made it through unscathed. Once the West Gulf Squadron took

New Orleans, Union efforts shifted back to the Gulf and closed Mobile in

August 1863. With Mobile and New Orleans out of the war, fighting shifted

west to Texas, which removed Florida even farther from hostilities.

On the east coast, Union attempts to take Jacksonvil e met with resis-

tance. Although the North was unable to hold the town, several ships were

left at the entrance of the St. Johns River to stop blockade-runners. De-

spite the Union’s best efforts, traffic persisted along the river, and northeast

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 401

Florida remained in Confederate hands. Union strategy focused on impor-

tant ports in South Carolina and Georgia, leaving few resources to maintain

a permanent presence along the St. Johns. Throughout the war, and despite

several battles, northeast Florida remained a contested theater, but always

secondary to events farther north.

Meanwhile, the South strived to defy the blockade. Quiet sailing ships

and fast steamships burning smokeless coal waited for moonless nights to

“run the blockade,” bringing material for war, medicines, foodstuffs, and

scarce luxuries into southern ports. Shal ow waters and smal inlets pre-

vented larger ships from gaining access and created perfect hiding places

for shallow-draft vessels trying to avoid the blockade. Captains and crews

risked their lives to evade Union ships, but could earn fabulous profits if

successful. The Union pursued blockade-runners relentlessly, capturing,

burning, and sinking the ships they caught. Two such ships,

Scottish

Chief

and

Kate

Dale

, are located in the Hil sborough River that flows into Tampa

Bay. The stern-wheel steamship

Chief

and sailing vessel

Dale

were loaded

with cotton when a Union raiding party burned them in 1863. Although in

shallow water near a historic shipyard on the river, the remains were hidden

by murky water until an archaeological survey sponsored by the Florida

Aquarium discovered them in 2008–9.

proof

Among the blockade-runners attacked was the two-masted schooner

Wil iam

H.

Judah,

in Pensacola Bay. The vessel was moored at the Pensacola

Navy Yard, which was under Confederate control, while being readied for

further service when, early in the morning of 14 September 1861, a Union

party from the warship USS

Colorado

pounced, setting fire to the ship. The

Judah

broke free of the wharf and drifted west with the tide until sinking

opposite Fort Barrancas.

More than twenty known Union vessels met their demise in and off Flor-

ida, as well as a score of British and international vessels. Only a few have

been discovered and documented archaeological y. One of these vessels was

Maple

Leaf

. The 173-feet-long vessel was built as a luxury passenger steamer,

but the Union converted it to a troop transport. In 1864,

Maple

Leaf

was

traveling on the St. Johns River carrying 400 tons of gear, including personal

possessions and supplies, when it hit a Confederate mine (called a torpedo

at the time) and sank. The ship ultimately settled to the bottom of the river,

where it was covered by more than seven feet of mud. The mines were ef-

fective; within six weeks, two other vessels met the same fate, and a third

followed soon thereafter.

Maple

Leaf

was rediscovered in the 1980s, and the

State of Florida and the maritime archaeology program at East Carolina

402 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

University partnered to excavate a portion of the shipwreck. Artifacts re-

covered enabled historians to understand what possessions Civil War–era

soldiers kept with them, such as photographs of loved ones, personal plates

and eating utensils, sewing kits to repair shoes and clothes, and a variety of

items that helped them to endure warfare, discomfort, loneliness, and long

absences from home. Today,

Maple

Leaf

artifacts are displayed in museums

in Tal ahassee and Jacksonville.

Just after the Civil War, the Navy’s worst nonwartime disaster occurred

off Tampa Bay. The tug USS

Narcissus

was traveling south from Pensacola

to round the Florida peninsula and continue to New York when, along with

USS

Althea

, she was caught in a storm off Tampa’s Egmont Key.

Althea

man-

aged to ride out the storm, but high waves breached

Narcissus

’s hul and

caused the ship’s steam boiler to explode.

Narcissus

sank and all hands were

lost; only a few pieces of the ship and the body of a fireman washed ashore.

The shipwreck site was partial y salvaged by treasure hunters in the 1980s,

though the artifacts they recovered were never conserved and the salvors

eventual y threw away the rusty and corroded lumps of metal. Luckily,

Nar-

cissus

was investigated archaeological y as part of the Florida Aquarium’s

Tampa Bay Shipwreck Project and, at this writing, has been nominated to

join Florida’s Underwater Archaeological Preserve system.

proof

Reconstruction and Maritime Industry

After the war, steamboat traffic contributed to reconstruction of Florida’s

economy and also to the creation of a new industry that came to be called

“tourism.” Clear, spring-fed rivers, graceful overhanging trees festooned

with Spanish moss, and an array of unusual wildlife drew visitors by the

thousands to the peninsula and Panhandle. Steamboats travelling along

slow-moving and easily navigable waters hosted some of the first tourists

to Florida’s natural attractions and helped promote the state as an exotic

destination. Tourists helped to encourage maritime interests in general and

boating trips of al types increased in these decades, providing a variety

of excursions in and around Florida’s waterways. Regular steam packets to

various towns increased in number, as did vessels which serviced north-

ern cities such as New York. By the late nineteenth century, Florida’s wa-

terways hosted ships from Charleston and Savannah on their ways to Fer-

nandina and Jacksonvil e. Off the St. Johns River, Harriet Beecher Stowe

wrote her famous letters “Back Home,” and she became a tourist attrac-

tion in her own right. Side-wheelers and stern-wheelers moved agricultural

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 403

goods, merchandise, mail, construction materials, groceries, and passengers

throughout the state. Steamboats also carried cotton from interior agricul-

tural regions to coastal ports for shipment to foreign manufacturing centers.

Not until the advent of cross-Florida railroads in 1861 and afterwards, which

moved people and goods faster and cheaper, did steamboating on Florida’s

rivers decline.

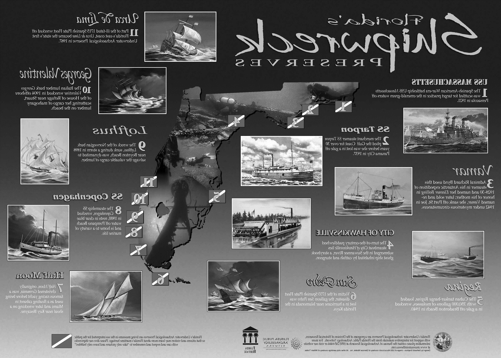

A few remnants of the state’s steamboating heritage exist as ghostly

wrecks in tannin-stained river water.

City

of

Hawkinsvil e

was the largest

and last steamboat on the Suwannee River. Built in 1896, the stern-wheeler

was 141 feet long with two decks. She moved along the river between Cedar

Key, Branford, and Old Town until abandoned in 1922. Tied up on the west

side of the river near Old Town,

Hawkinsvil e

was left to slowly sink into the

Suwannee’s dark depths. Now a state Underwater Archaeological Preserve,

Hawkinsvil e

provides an exciting diving opportunity and a tangible link to

the steamboating era in Florida.

Into the last decades of the nineteenth century, industries such as tour-

ism, lumber, and agriculture helped to boost shipping and increased the

number of vessels along Florida’s coastlines. Northern entrepreneurs took

notice of postwar Florida’s prospects and invested money in a variety of

mil s that fed ports like Jacksonvil e and Pensacola. The cal for lumber

proof

continued. And there was new demand for naval stores and phosphates,

the latter an important component of fertilizer. Tampa, especial y, benefited

from a phosphate boom in the late nineteenth century. Smaller ports like

Apalachicola, St. Marks, and Cedar Key also grew, but they lacked the infra-

structure and convenience of major harbors. Southern portions of the state

experienced increased production in fishing, cattle, and citrus.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Florida’s lumber industry was

engaged in heavy trans-Atlantic trade. It was the Florida ports that made

possible shipments of lumber to foreign markets. Those sales led to harbor

improvements and facilitated the growth of several port cities. Pensacola

became the third-largest seaport on the Gulf coast. International demand

for tar and turpentine increased as wel and Florida became a major supplier

of naval stores throughout the world.

While most ships loaded with pine, oak, and tropical hardwoods from

Florida forests made their voyages successful y, some were lost on the state’s

shores.

Lofthus

was a Norwegian-owned, barque-rigged, iron-hulled sailing

ship when she wrecked in 1898. Loaded with lumber, the ship left Pensacola

bound for Buenos Aires, Argentina, when she was caught in a storm and

grounded off the east coast of Florida near Boynton Beach. Now lying in